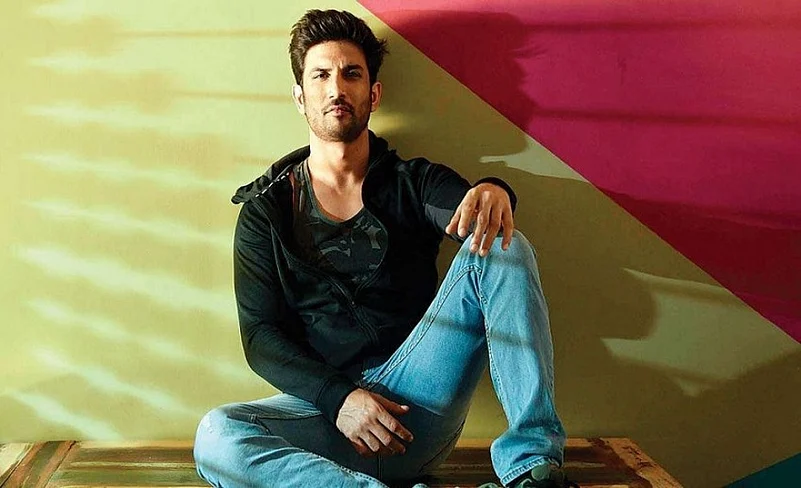

It’s been almost six weeks since there was a “death by suicide” a couple of kilometers away from our home in Bandra. The passing of Sushant Singh Rajput, who by all accounts was a bright, talented and an accomplished actor, has sent the nation spinning into all kinds of debates on bullying, alienation and nepotism. However, within the realms of this TRP-driven dizzying debate, we have managed to avoid delving into the core issue behind his death: the sheer inadequate social and medical infrastructure which his reality inadvertently became defined by. The puncture in his “safety net” within his internal and external frameworks ultimately let him down when grappling with the clinical severity of major depressive disorder in his most pressing hour.

The sound of traffic is as soft as the waves at the Bandstand promenade under the ominous, invisible veil of Covid-19. The signature ledge usually scattered with a cascade of monsoon lovers dipping into deep-toned umbrellas is barren and empty. In fact, it seems as though there are no lovers nor does it feel like there is any love period. In a parched world where it felt like love had permanently died, we woke up on a Sunday to find that this actor was hanging from a ceiling fan. We were shocked yet anaesthetized to “death” as a concept from already living in a dystopian reality show for three months. So, we went about the usual fiddling with our masks and gloves and buying vegetables like robots on a Sunday. We then went home and watched news reports and footage of Sushant’s Bandra perfect flat on our phones, a paradise that looked like it could be from any big city gone terribly wrong.

Weeks later, the ongoing fiery debate on nepotism continues with a certain literati at the forefront shouting out the so-called barriers to access of Bollywood’s invisible gates, calling it “elitism” while carefully protecting their own coveted circles because those don’t count, of course. An actress perennially motivated to exploit every moment for a few extra points blames everyone under the sun for Sushant’s demise but then mysteriously goes silent and under cover in Manali when the Mumbai Police send her an official notice for questioning. The wild goose continues to be fueled by a TV anchor whose counter conspiracy theory gives fodder for a Mumbai version of “Delhi Crime”. Suddenly, the Mumbai Police has a new glam quotient—a likely pleasant distraction from the mundane “Covid busting” and patrolling of Covid car checkpoints at various corners of the city.

“He was lonely,” people said of Sushant over the past few weeks. Yes, but how is “lonely” prohibitive? Lonely, during this harshest lockdown by global standards, for this creative, restless soul didn’t quite pan out the way he thought it would. Lonely, during this lockdown for Sushant and many living alone might have meant a time of less human contact with fewer pats, lesser eye contacts or perhaps no physical contact period, which would further deplete already challenged serotonin, oxytocin and dopamine levels.

In the face of India not having an efficient “911” dial in equivalent for emergency medical needs, it’s somewhere more evident that this actor didn’t have a “buddy system” that he could rely upon. Forget 4 am, he didn’t have a Sunday mid-day friend he felt safe enough to call to help rescue him from the acute and piercing heartache that was inevitably screaming its loudest to triumph over his sense of hopelessness. Or maybe he called and no one picked up. In the Hollywood film “Sylvia”, a biopic on the brilliant contemporary American writer “Sylvia Plath”, there’s a scene where Gwenyth Paltrow depicts the writer as having run out of the house in the dead of winter to try to make that one proverbial last call for help from a pay phone. The call never connects. She runs back into her home and sticks her head into her oven and burns to death leaving her toddler children alone at home.

At the time of writing this article, I googled “suicide lines in Mumbai”. I found three numbers that were listed. But none of them worked. Perhaps others exist but in that Sylvia Plath like moment – only decades later for Sushant – it was likely just that one call he needed.

In their police testimonies, three of Sushant’s medical caregivers stated that he had stopped taking his medication days before he passed away. In all the humdrum on TV, one hasn’t heard a single conversation about how an integrated, coordinated and (PCP) primary care physician-driven mental healthcare delivery system can prevent gaps in psychiatric medication compliance. Why did Sushant lose faith in the efficacy of his drugs and the treatment regime he was under with multiple doctors?

As imperfect as care delivery systems in the West have become, coordinated PCP-driven care exists with the goal of containing costs and also preventing gaps in access to effective treatment regimes. In India, we are not there yet, both in terms of mental health being a national public health priority and in developing medically efficacious coordinated systems of mental health care in the private delivery system.

In my senior year of college, one of my closest friends was suffering from major depressive disorder. I didn’t really know what depression was at that point until I saw that she was unable to get out of bed in the morning for two weeks straight. She couldn’t physically move, couldn’t eat much, or attend class for over 14 days. She would panic at the thought of having to spend any time alone and needed to have every minute of her day accounted for in a planner in order to avoid having thoughts of hurting herself. When we took her to the university psychiatrist, we realised that her mental health care journey was going to be. This, along with a closely monitored and titrated medication regime, was going to be part of the canvas of her life which she would have to manage. Fortunately with its share of ups and downs, she was luckier than Sushant to have been able to pull through similar moments of despair.

Dil Bechara enables us to celebrate the life of a talented young man who convincingly spoke at an IIT Bombay session a few years ago of his humble beginnings and how he craved “success” as far as “money” and “recognition”, only to realise that without “passion”, there could be no success. What comes through about him in that talk is that somewhere he craved deeply to “belong”. A most human desire – to be seen as being “enough” by a real or imagined “A” list group that he defined his sense of self-worth upon. Nothing short of “this” group seemed to be enough for him. It’s as if success in his mind was like a neural pathway of an “action potential” – an all or nothing response. There was nothing in between. The perception of “failures” and disappointments were so acute that he didn’t have the resilience to bounce back and redefine himself like others had the grit to.

Yet, the nepotism argument is the greatest irony of all. How does this notion remotely hold true if the industry’s leading production house that gave Sushant his first big break (Shuddh Desi Romance) cast him – a complete outsider – on his own account? Furthermore, if there was nepotism, how would have this same production house given him a second break? So, unlike the valid “reparations” argument from a variety of segments claiming that there’s been a pattern of subjugation based on a series of historic events, we seem to be claiming convenient “nepotism” the minute things don’t go well for a particular reason or circumstance to suit convenience. Failure and disappointment are as deep a part of the entertainment industry as they are in any field perhaps, more so here due to the magnitude of stardust trade-off in terms of “recognition”, “fame” and “money”. Yet the reality is that creative discrepancies result in box office shortfall and subsequent strategic priority shifts to “can” a project. That does not make it “nepotism”.

Globally known YouTuber PewDiePie did a special tribute to Sushant a couple of days ago, highlighting that same IIT Talk from a few years ago. He highlighted how this brilliant young DCE entrance exam 7th ranker nationally spoke of “persisting”, yet perhaps somehow didn’t have the reserve to persist through the lowest of the valleys that are thrust upon us through curve balls when we least expect it. Watching PewDiePie with his hundreds of millions of viewers, I couldn’t help but think to myself that this is somewhere what Sushant exactly would have wanted -- it would have been the kind of lifetime achievement that he would have sought as being valuable enough.

At the end of the day, Sushant’s passing away reminds us all that it’s that empty ledge at Bandstand amidst this Covid monsoon that’s our northern light. Love. Dil Bechaara is an adaptation of the heartbreakingly wonderful, Fault In Our Stars – the story of another life interrupted. Let us look up at the heavens this weekend for Sushant, our avid lover of the stars, and remind him that there was never any fault in his stars. He was truly always enough and more.

(The author is a writer, director & Tagore fusion singer with a Masters in Public Health from Columbia University. Views expressed are personal.)