‘Will you let me talk?’ pleaded one of the participants on a TV debate. ‘This is not fair!’ he slammed his fist on the table. His red-faced opponent had the exact same complaint. The impassive moderator between them reminded me of Facebook.

The social media giant has been attacked from all sides in the recent past, by conservatives for what they perceive as liberal bias; by liberals for white nationalism; by human right activists for gender-based harassment, live streaming of violence; by governments for fake news; and by civil society for rigging elections. The list is long, and no one is satisfied.

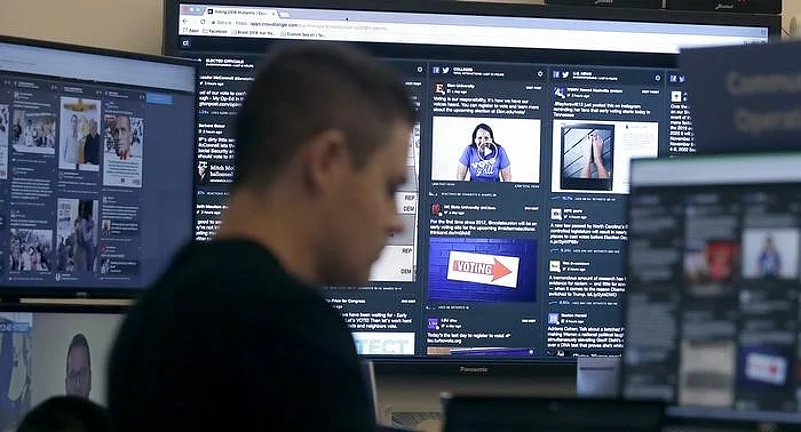

Moderating is not an easy task in any case, and certainly not when the numbers are staggeringly huge. Every minute around 510,000 comments are posted on Facebook, more than 500 hours of video are uploaded on Youtube and 350,000 tweets are sent out (in many different languages). And this happens every minute. Imagine curating and managing this enormous amount of data -- what is okay to be seen and shared, and what is to be deleted. There was a time when the governments decided these issues, now that role has seemingly moved to tech companies -- this is the challenge that lies at the heart of the debate around free speech and expression.

The social media platforms have the power to shape the contours of online speech. It ranges from drastic measures, like deleting posts, to a more subtle intervention that decides on the virality and visibility of posts. But with power comes responsibility. Their decisions are often under scrutiny, vague and contradictory. And given the overwhelming evidence of social media in influencing elections or inciting violent mobs, the need to moderate wisely is even more critical.

Under pressure from civil society and various governments, Facebook developed a long set of rules that governs how the platform handles misleading or dangerous content. There is no legal standard for these decisions; they are mostly based on the company’s own internal guidelines. In reality, however, these rules can be fairly opaque, inconsistent and difficult to follow, and their application varies as per the discretion of the people in charge. It is no surprise that Facebook has been fighting accusations of bias – right from the US President claiming that it is anti-right wing, to the current controversy of being pro-right wing in India. But think about it: how do we even prove bias.

Pointing out instances of a post being deleted or profile being removed, on a case-by-case basis, is too simplistic. It can make headlines, but does not necessarily point to a systemic flaw. For print media or cable TV, it can perhaps be done by comparing two sets of data, with similar content and then checking if they were treated the same way. This is to be done, not just once, but multiple times. However, when it comes to social media, it’s much more complex.There is simply too much data floating around to compare or evaluate.The networks themselves are hesitant to share information due to privacy concerns. And, hence, bias is tough to prove.

But the clamour continues. Around the world, there are increasingly aggressive demands for platforms to monitor and control content that is objectionable. At the same time, tech companies need to also be more transparent about how this is being done. The truth is that the sheer scale makes it impossible to perfectly enforce rules. Millions of users all over the world are constantly uploading, commenting, sharing and liking. There are bound to be errors. Even though the Artificial Intelligence (AI) system flags 3 million items every day, if the moderation rate of error is 10%, that means there are 300,000 moderation mistakes per day.

Moving from what it gets wrong to what is right. Defining ‘right’ is fairly complicated. For example, Facebook has been criticised for its handling of hate speech. It’s an issue that it has been grappling with for years, as so much can lie in between. There is a cultural context, as different countries have different values, beliefs, customs and languages, making it hard to interpret what is acceptable or not. The idea of global uniformity is tough to define.

The other issue is: who or what does the moderation. Facebook has outsourced this critical function to third party operators and the AI (especially during the pandemic). However, the company has begun to realise that the AI used to flag offensive content has its own limitations, especially when it comes to hate speech. And so do humans. Moderators are not really experts. They have been given a set of formulas to follow. But it is very hard to create a policy that captures the messy spectrum of human communication into a set of rules.

Nobody is sure about how this works. But we need to keep trying. The internet needs to be a healthier and happier place. As a corporate driven by profit, Facebook has time and again realised that developing process and solutions can have a significant financial, political and opportunity cost. But they have no option.

Going forward, we need greater transparency about what is taken down and why. As well as what portion of takedowns are appealed and reinstated. Although disclosures are being made, there is much that is still unknown about moderation and appeal in different countries and contexts. Civil society and experts need to be more engaged on how to regulate content. There needs to be new thinking to create accountability, increase transparency and have a structure for appeals.

The vast world of social media keeps evolving. The rulebook keeps changing. The moderator needs to be accountable, and so do we.

(Ekta Kumar is a writer, columnist, artist and works closely with the European Union on gender and civil rights-related issues. Views expressed are personal.)