Any discrimination is demeaning, if not deadly, and I got a taste of it when I was stopped rudely at the entrance of a glitzy mall during my time in West Asia. My colour and demeanour weren’t welcoming. My Western colleague, who was accompanying me, had no such problem. Though the country I lived in then offered riches, I had to endure the humiliation that was an upshot of the widely practised policy of single Asian males not being allowed in public places, particularly on holidays. It was not written anywhere, but the differential treatment often surfaced. Apart from my Indianness, my birth religion put me at a disadvantage in a region that still does not allow a Hindu temple. And when an editorial dispute arose at the workplace over a certain news article on Kashmir, I lost the debate even before it began. My views were dismissed because I am an Indian—and a Hindu.

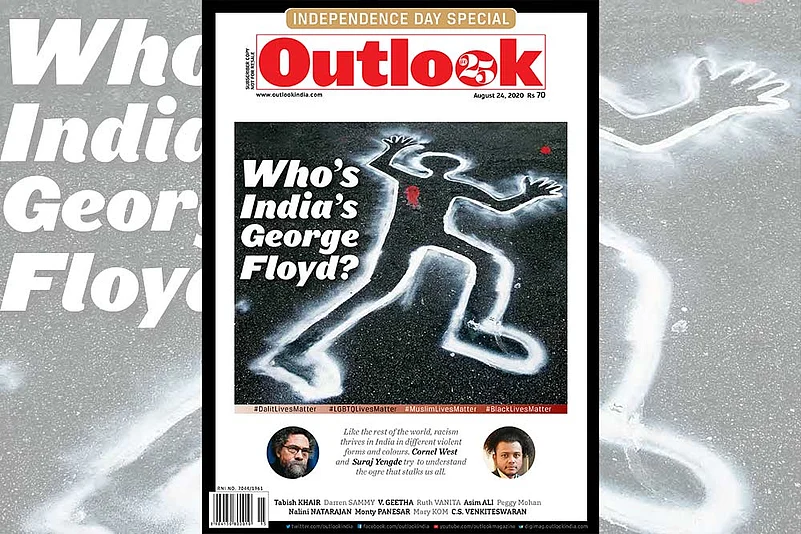

We are one—human beings—but our biases divide us, exposing fault lines based on race, caste, creed, and everything else that make up our identity. So widespread is the evil that none is immune to it—especially the US, which in recent months has been witnessing upheavals since a White policeman pinned a middle-aged Black man to the ground, pressed a knee on his neck for more than eight minutes and snuffed out his life. A disgrace as it was, George Floyd’s death, however, has refueled a movement, #BlackLivesMatter, and triggered nationwide churning, calling for police reforms and a change in attitude.

But that is in the US. In India, though, we seem to have made peace with our proclivities without pondering much about the price it exacts from those at the receiving end. For that matter, so normalised is the practice that we possibly even do not consider ourselves guilty. I remember my growing-up years when almost everyone in my surrounding world would contemptuously classify people from a neighbouring state as good enough only to be plumbers or cooks. It’s only during my early adulthood, when I went to live and work in the state, that I realised how grossly wrong the childhood lessons were.

The fortuitous and rare enlightenment apart, we generally remain prisoners of our prejudices. Irrespective of whether we acknowledge their presence or not, biases remain rife and the current COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how prevalent they are with many fellow citizens from our Northeast being mocked and taunted as “Corona” for their looks. The harassment ranged from verbal abuses and heckles to physical attacks. Ironically, reverse-racism blights the Northeast too, where so-called non-natives are routinely discriminated against for being “outsiders”.

Of course, we outrage over a few odd instances occasionally before slipping back into silent acceptance of the bigotry dished out routinely in this country. Cases such as an upper caste assault on a Dalit groom for daring to ride a horse to his wedding make transient headlines—nothing else. Our Constitution enshrines equality, but fissures continue to fester. North Indians discriminate against South Indians over culture and colour, caste divides Hindus, while Muslims and Christians have their own divisions over who converted when and from what background. The pandemic of inequalities, I am told, has not spared even what are supposed to be egalitarian newsrooms. According to a survey quoted by the Economist recently, 105 of the 121 top editorial positions in India are reportedly held by upper castes and I happen to be one of them.

In this Independence Day special issue, Outlook turns its gaze on the virus of racism that we as a nation have failed to conquer in the more than seven decades as a free country. George Floyd is not just an American phenomenon. We too have a similar share of crying shame that shackles us from being truly free.

ALSO READ