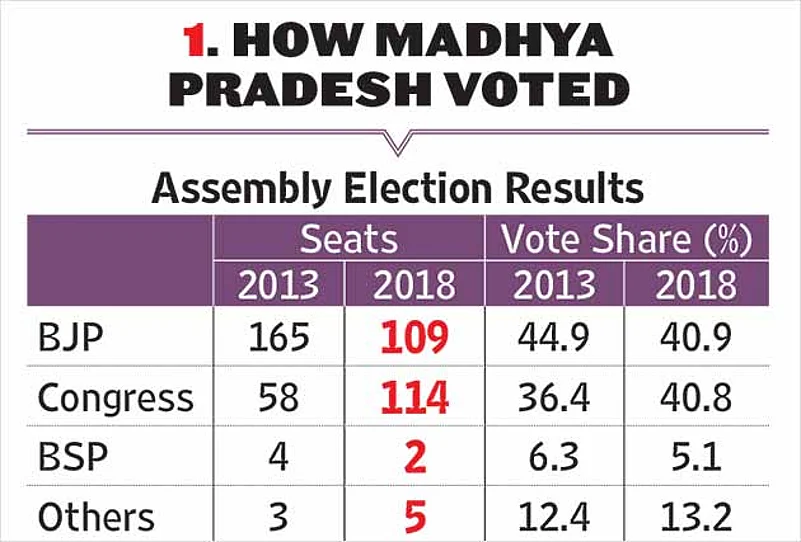

Badlav and takkar ka chunav were two oft-heard expressions used by many journalists reporting from the state during the run-up to the Madhya Pradesh assembly elections. In the end, when results were declared on December 11, both turned out to be true—the BJP lost power after 15 years, but not before giving a tough fight, resulting in a nail-biting finish, to the Congress. After spending a decade-and-a-half on the opposition benches, the Congress has eked out a narrow victory, winning 114 seats, two short of majority (Table 1).

The return of the Congress in Madhya Pradesh has a very special significance for it, not just because the state had the highest number of assembly seats compared to all other states that went to polls along with it or because of its central geographic location, but also because it was a classic bi-party competition where third players have often remained distant. An improved performance of the Congress here signifies its ability to take on the BJP in a direct face-off. Madhya Pradesh also mirrors the current Indian story of agrarian unrest, unemployment, economic upheaval and social squabble.

Voter Fatigue

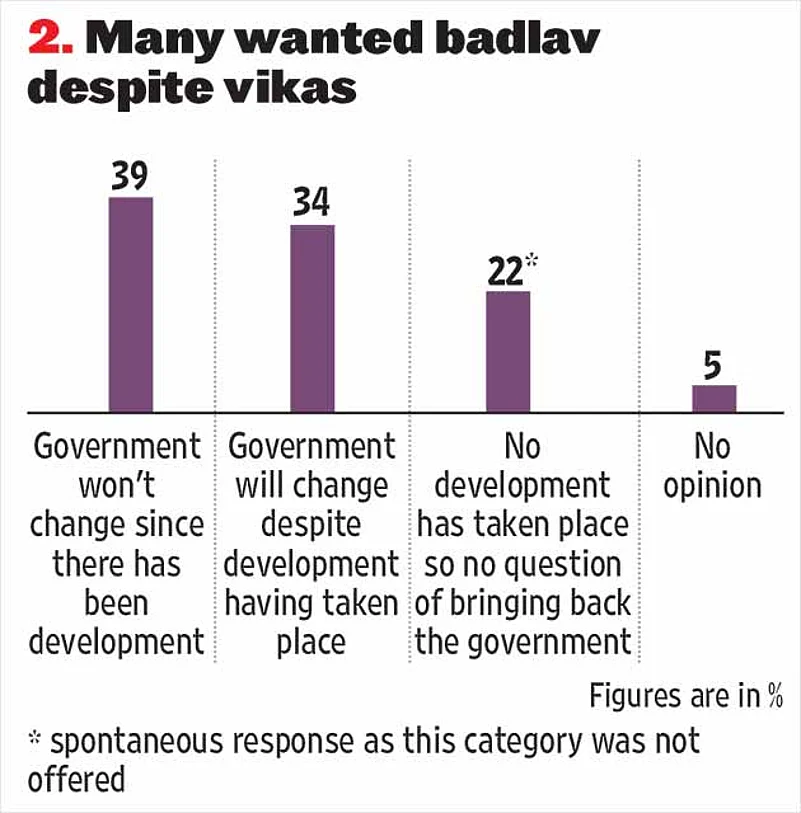

One of the main reasons for the BJP’s defeat seems to have been voters’ fatigue with the Shivraj Singh Chouhan government. Many voters were so tired of his long rule that even those who thought that development had taken place in the last 15 years were willing to overlook it and voted for a change of regime. In the post-poll survey done by Lokniti-CSDS among 5,818 randomly selected voters from across the state, over one-third said that they were certain voters would vote out the BJP government despite development having happened. This sentiment, combined with about one-fourth who thought that little or no development had taken place under the BJP, was enough to deny a fourth consecutive term to the saffron party (seeTable 2).

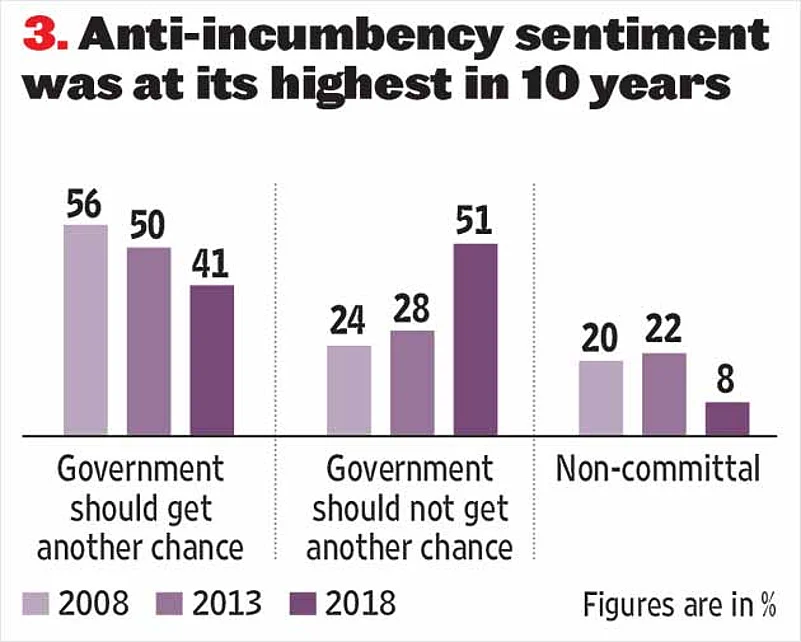

The yearning for a regime change can also be seen in another survey finding. For the first time since the Chouhan government first got re-elected in 2008, the proportion of those wanting his government to go was greater than the share of those wanting it to continue, 51 per cent to 41 per cent. What’s more, the change-seekers this time around were twice as high as those who had wanted change in 2008 and 2013 (Table 3).

Adivasi Anger

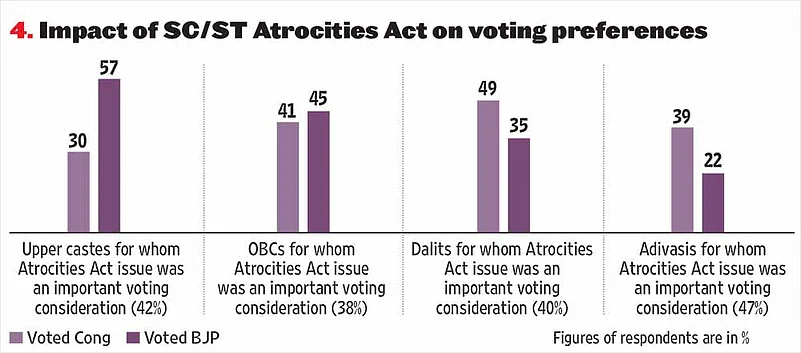

Voter fatigue alone, however, is an inadequate and a somewhat simplistic explanation for the BJP’s defeat. Coupled with fatigue there was dissatisfaction and perhaps even anger among a certain section of voters, particularly the adivasis. In the survey, when asked specifically about the amended SC/ST Atrocities Act, half the adivasis were of the opinion that it had been a “very important” voting consideration for them. Of them, about two-fifths ended up voting for the Congress (see Table 4). In fact, the impact of the issue on the adivasi vote was much more pronounced than its impact on the Dalit vote. Among adivasis who saw the Atrocities Act issue as being very important, the Congress’s vote lead over the BJP was found to be 17 percentage points, compared to just 10 points among adivasis as a whole. Among Dalits, however, there was no such pattern. Even as many Dalits were also found to attach great importance to the issue, their vote for Congress or BJP does not seem to have been entirely determined by it. Dalits who saw the Atrocities Act as being an important issue were as likely to vote for the Congress or the BJP as Dalits who did not. That said, the Congress performed extremely well among Dalit voters, securing half their votes. It may have performed even better had it tied up with the BSP. However, on the flip side, such a tie-up would have run the risk of alienating the small but significant proportion of upper caste and OBC votes that it got.

The Class Dimension

There is also a class dimension to the BJP’s defeat. While the BJP was able to retain much of its support among the economically well-off sections, among the weaker sections support for it fell drastically. Only about 39 per cent of lower class and poor voters voted for it, a good five percentage points less than in 2013. Inflation on account of rising fuel prices and unemployment may have had something to do with this. The two emerged as the top issues among voters during the survey—one in five voters spontaneously said mehengai and a similar proportion said berozgari on being asked what the single most important voting issue had been for them.

The much talked about issues of agricultural distress and unrest may have played a role in the BJP’s defeat, but not to the extent being portrayed in the media. The Lokniti survey found farmers to be divided on class lines when it came to their voting preferences. While a greater share of votes among landed farmers was secured by the BJP (40 per cent) compared to the Congress (35 per cent), among landless farmers Congress got higher support (45 per cent) compared to the BJP (41 per cent). Also, interestingly, the BJP swept most seats in and around Mandsaur, where police firing on farmers claimed six lives in June 2017. That said, whatever their political choice, the crisis faced by farmers in Madhya Pradesh is indeed acute. Only 27 per cent of farmers reported getting the right remuneration for their crops often. About 26 per cent said they get it only sometimes and 44 per cent reported rarely or never getting the right price. Also, 60 per cent of farmers reported not having benefited from the ‘Bhavantar’ or the price differential scheme.

Scindia-Nath Combination Clicked

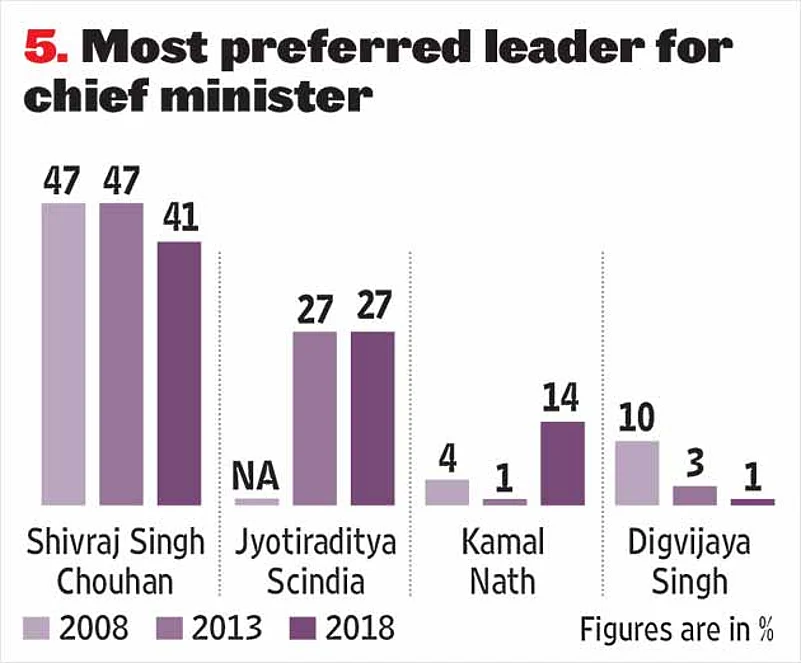

It seems that not projecting a chief ministerial face for the election might have worked in the Congress’s favour. While the Lokniti survey found Chouhan to be voters’ most preferred leader for the chief minister’s post at 41 per cent, the combined popularity of Congress leaders Jyotiraditya Scindia (27 per cent), Kamal Nath (14 per cent) and Digvijaya Singh (one per cent) was enough to match Chouhan (see Table 5). More importantly, the survey found that supporters of both leaders ended up voting for the Congress in equal measure; unlike in the past when Congress had failed to capitalise on the anti-incumbency sentiment due to factionalism among its ranks. While the unity shown by Scindia and Kamal Nath in the run-up to the polls may well have been a facade, it served its purpose, ensuring that the Congress did well, particularly in Chambal, considered to be Scindia’s area of influence, and Mahakoushal, where Kamal Nath has traditionally held sway. Both leaders were also found to be highly liked by voters—Scindia by nearly three-fourths and Kamal Nath by two-thirds. Scindia’s likeability, in fact, was found to be as high as Chouhan’s and higher than Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Candidate Selection

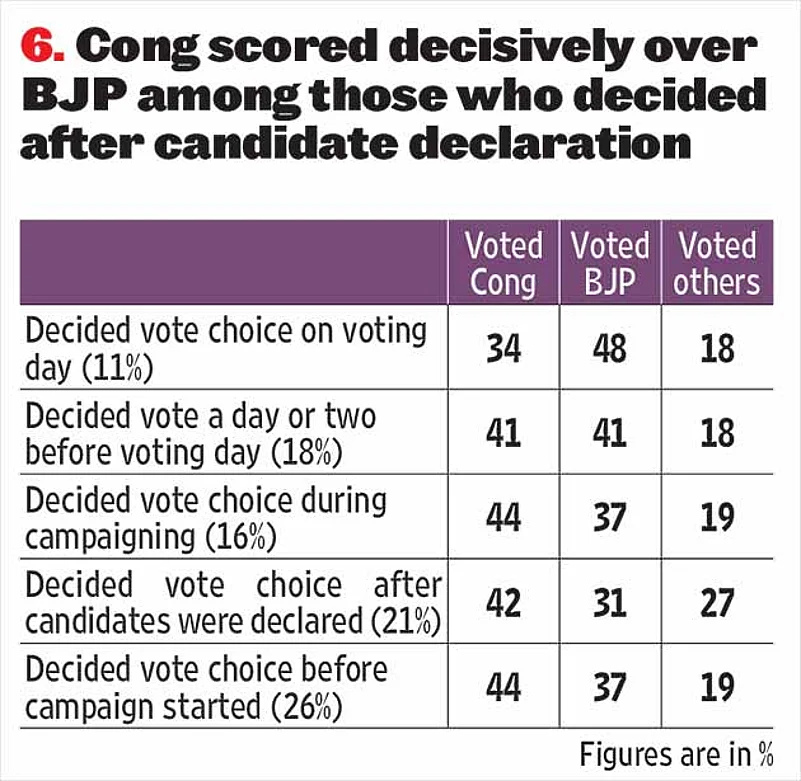

The Lokniti survey also indicates that the Congress victory may have also been on account of comparatively good candidate selection. About one-fifth of the voters said they decided who to vote for after the candidates were decided by the political parties, and among such voters the Congress’s vote lead over the BJP was found to be a whopping 11 percentage points (see Table 6).

Did Soft Hindutva Work?

In a state with over 90 per cent Hindus, while the Congress’s gambit of trying to appear more Hindu than the BJP by promising gaushalas in every panchayat, commercial sale of gaumutra and building a ‘Ram van gaman path’ may have attracted a section of Hindu voters towards it, it would be mistake for the party to believe that this is what worked primarily. The post-poll survey in fact provides evidence to the contrary. When asked about how important the cow protection issue had been for them, over half the voters said it had been “very important”. Among such voters, however, the BJP enjoyed a huge 10-point vote lead over the Congress. Similarly, the Congress trailed the BJP among Hindus who reported visiting temples on a regular basis. It did fare better than the BJP among Hindus who said they rarely or never visit temples.

Looking Ahead

It is being argued by some political experts that even as the BJP has lost power in Madhya Pradesh, it may still do well in the state during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, owing to PM Modi’s popularity. Lokniti’s survey data, however, shows otherwise, at least as far as Madhya Pradesh is concerned. Nearly 91 per cent of Congress voters in the state indicated that they would vote again for it during the 2019 elections. Two-thirds of Congress voters were also of the opinion that it’s better to have the same party rule both in Delhi and Bhopal, which perhaps indicates that they are anticipating a Congress government at the Centre after six months. Further, Modi’s likeability was found to be only slightly higher than that of Congress president Rahul Gandhi. Considering that prior to the assembly elections Madhya Pradesh was being described as a bellwether state for Lok Sabha polls by many analysts, these findings are significant and, come May 2019, may well spell trouble for the BJP. This is, after all, the state that is home to 15 of the 38 Lok Sabha constituencies nationwide that the BJP has either never lost or lost just once since 1989. A bastion of the BJP has well and truly fallen.

(Sisodia and Bhatt are professor and associate professor, respectively, at Madhya Pradesh Institute of Social Science Research; Sardesai is research associate, Lokniti-CSDS)