Indian politics has undergone a major transformation since the time of independence, and during every epoch of this transformation, people have shown enormous faith in a single leader to find solutions to their problems.

Even within the system of competitive political parties, based on democratic decision-making structures, people have always looked for charismatic leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, etc. Such leaders were able to sustain their support within the background of a welfare state, which not only provided the basic material support system but also regulated and controlled the small section of elites.

Such a state-dominated political economy was able to control the inequality where the top one per cent was having around only 10-16 per cent of wealth till the 1990s. This has multiplied three-fold after the formal adoption of neoliberal political economy from 1990 onwards, which has created a condition where wealth is slowly getting more concentrated in the hands of a few elites. This coexists with a political system that, through a multitude of political parties, has democratised and expanded the political rights representing all sections inclusive of the socially and economically vulnerable.

The understanding of this contradiction is necessary to comprehend the rising populist forms of government not only in India but all over the world.

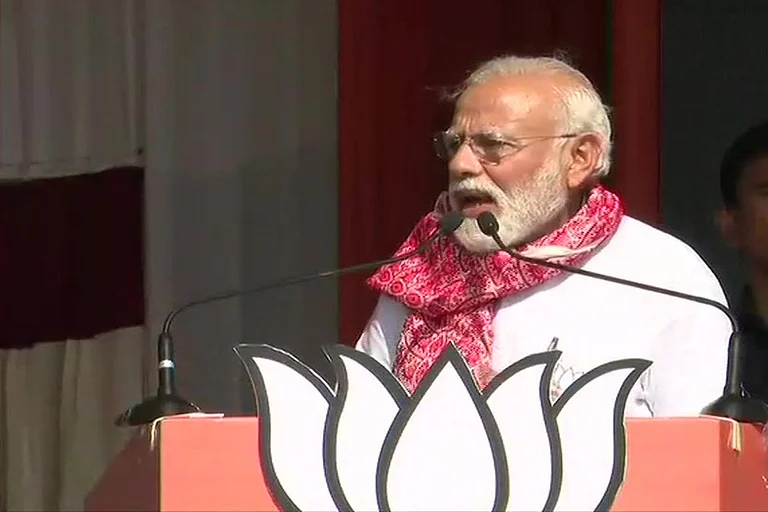

The rise of a Right-Wing populist government in the form of the BJP and its leader Narendra Modi is beyond the Weberian charismatic leader based on traditional authority. More than individualised, in contemporary times, the charisma of the leader reflects his power in a social context where power is used for historical revival and revenge in recreating the glorious past.

As political analyst Ajay Gudavarthy argues, populist politics during the Congress regime was more confined to electoral politics, but in contemporary times, it moves beyond the political processes and institutions in promising equality and finding solutions to all problems through cultural transformation.

The main difference between the Left Wing and Right Wing populism lies not in identifying the division between “commoners” and “elites”, but in finding the solution to overcome this division. For example, Hugo Chavez of Venezuela can be identified as a Left-Wing populist government. During his first term in office between 1999 and 2001, he implemented a social welfare programme “Plan Boliver 2000” involving 70,000 soldiers in addressing many issues, including infrastructure, health and food. During his second term between 2001 and 2007, he implemented social programmes through revenue from oil resources. The social welfare programme “Bolivarian Missions” addressed many issues, including poverty, education, health, hunger, etc.

The Left Wing populist government tries to find solutions within the material realm while addressing inequality and fighting against the elites. But the Right Wing populist government tries to find solutions for economic inequality and other social evils in the cultural realm. Rather than targeting the economic elites, they identify the “other” within the cultural sphere to mobilise the majority belonging to the dominant cultural group in society.

As Paul Pierson has identified that in the Right Wing populist governments, anti-economic elitism remains mere rhetoric, and further the economic elites play a significant role in sustaining the rule of Right-Wing populist governments as cultural-emotional appeals and actions overshadow the existing material inequality.

We can trace these aspects in many of Donald Trump’s political actions which included identifying Mexican immigrants as criminals, doubting Mexican American Judges, Islamaphobic and racial undertones in excluding minorities and vulnerable sections when the economic inequality was rising in USA. We find such evidence in the Indian context where the emotional cultural appeal of the Right Wing populist government has distracted and covered the growing inequalities in the contemporary period.

But the emergence of the BJP, in the name of fighting against corruption and anti-economic elites, has been a mere rhetoric without much transformation at ground level. The corporate donations to both the BJP and the Congress constitute more than 90 per cent, where the BJP pockets the major share. The incentives and tax exemption for corporates stood at Rs 10,811,30 million in 2018-19, protecting the elites from people’s money. Even during the pandemic, the wealth of Indian billionaires increased by 35 per cent. And the top 10 per cent holds more than 77 per cent of total national wealth. According to the OXFAM report on inequality, it would take 941 years for a minimum wage worker in rural India to earn one year income of a top executive in a leading corporation in India.

How then a pro-corporate political party was able to get continuous support from the masses? Here, as a typical Right-populist government, the Modi regime is trying to find a solution in the cultural domain by identifying “others” in minorities and leftists for the historical degradation of India.

The restoration of a glorious past is also not in terms of constitutional morality or material redistribution, but cultural resurgence excluding the minorities and dissenters. The BJP’s push for the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) was more in line with the institutionalised exclusion of Muslims, rather than helping the non-Muslim minorities. This is in line with the BJP’s cultural nationalism that includes Hindus in “Akhand Bharat”. The Indian Constitution, with its ideological basis of positive liberalism creating a welfare state, is in tune with the material transformation of hitherto economically and socially vulnerable groups.

The BJP’s politics of reservations for the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) violates the constitutional intent of helping socially vulnerable groups. More than material transformation, it revamps the “hurt pride” of the dominant caste due to the social welfare measure based on the constitution, which led to the rise of vulnerable sections.

Demanding reservation for other non-dominant OBC groups dissuades the Bahujan consolidation for constitutional rights, but, in turn, might open up for consolidation under cultural identity as Hindus. To foster such consolidation, the religious “hurt pride” of Hindus is evoked.

After the Ram temple inauguration, equating the coming of the temple as a solution to all problems, Modi said: “The Ram temple will stand witness to the emergence of a prosperous and advanced India”. Such evocative and emotional politics is a natural outcome of the Right Wing Populist Party, which pushes the truth from empirical to symbolic covering up the material inequality.

According to the Comparative Manifesto Project (2015), which surveyed 450 political parties from 41 countries, Right Wing political parties tend to invoke non-economic issues related to race, ethnicity, caste, religion, and migrants etc, to widen social division to cover up the rising inequality.

In such situations, how the populist leaders were able to sustain their support without major material transformation and creating hope for the people is worth observing. Populism, as a radical democracy, which has the scope to represent the interest of hitherto unrepresented, is giving a false consciousness among the people that mere mass participation in politics overriding the existing institutional structures, which were rationally created, based on deliberations and discussions, will give them power to change the world.

The Right Wing populist resentment against the constitution and its values reflects this attitude. Such false consciousness is being utilised by populist leaders through their emotional rhetoric speeches. The Post-Truth political environment, emphasising on emotional appeal than rationality, and easy access to technology, has carried such populist rhetoric as a sacred sermon without any critical engagement.

Right-wing populist focus in the cultural/religious sphere within the principles of neo-conservatism emphasises hierarchy and authority, which, in turn, is beneficial for free market elites to continue their activities without much resistance.

The democratic potentialities of masses are being tapped by Right-wing populists for protecting the interest of economic elites. In such a scenario, the Right Wing populist leaders assume a messiah role in attracting unconditional obligation from the masses as we are witnessing in India.

Venkatanarayanan Sethuraman teaches at Christ University, Bengaluru.