Population increase governs population size. Poverty, however, is determined by access to and use of resources, services, and opportunities. Therefore, it is important to consider population and poverty in their intrinsic relationship with inclusive development and health. The inverse association between population and resource access is not adequately explained by population growth alone. The initial Malthusian explanation of population checks has been replaced by a variety of trajectories extending its interpretations.

Worldwide population growth rates and average family sizes have decreased by about 50% over the past 40 years. Rachel Carson's Silent Spring published in 1962 and Paul Ehrlich's Population Bomb in 1968, took the doomsday neo-Malthusian idea to its zenith. But Julian Simon’s The Ultimate Resource first published in 1981, and then in 1996; and ‘The Resourceful Earth’ co-authored with Herman Kahn and published in 1984, established a critical counter-tradition by arguing that resource depletion is not always caused by population growth, especially when it affects underprivileged groups.

Contrarily, population increase propels innovations to support increase, which in turn further fuels growth—population and economic. Human ingenuity, therefore, is capable of resolving numerous issues. Despite growing populations, the quality of the water and air has improved because of technological innovations; and scientific research and empirical evidence have proved that poverty and misery have also decreased globally, albeit with increasing inequality.

Unlike the popular belief that population size is the root cause of all problems including poverty; scientific arguments have fairy well established that it is the nature of development, inclusive or otherwise, which ensure availability, access and utilization of resources, services and opportunities. Had population size been the reason, then neither would have China emerged as an economic competitor to the United States of America, nor Singapore would have ruled the trade in the East Asian territories. The most developed regions of India would have been Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh rather than the megacities, which rule the roost (of the market and the economy) today.

The unequal distribution of the social determinants of health including access to resources and opportunities, leads to health disparities. Inequality has long-lasting repercussions on social cohesiveness and trust, which has negative effects on health, and influences morbidity and mortality trends. Income, employment, housing, education, one’s social position, and social exclusion have both direct and indirect effects on health. There is evidence of a social gradient in health. Individuals in more privileged situations tend to have better health and experience lower mortality.

It is well known that differences and inequities lead to exclusion and prejudice. The determinants of poor health have been majorly attributed to poverty. Social exclusion has been taken for granted. Various groups are marginalised in most societies globally. The distinctive characteristic of caste in India makes it an exceptional axis for exclusion and marginalisation. Caste is a euphemism for poverty and low socioeconomic status. That health is influenced by caste, poverty, and geographical disparities in fairly well evident.

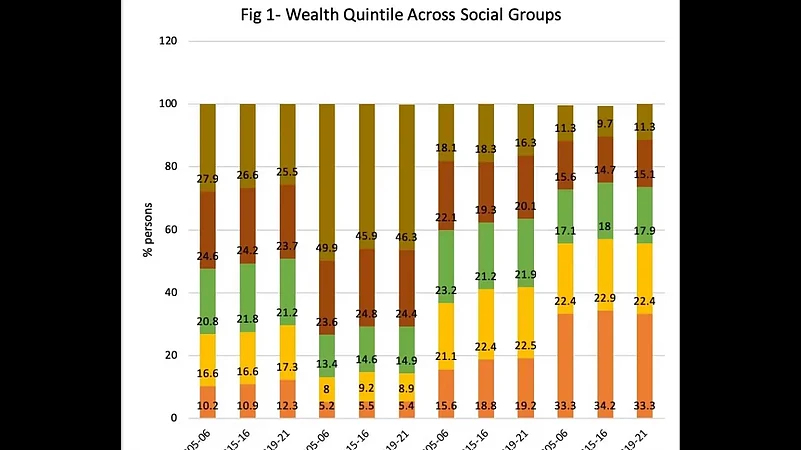

In comparison to the ‘other’ group, often synonymous to being privileged, the share of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes is higher in the poorest wealth quintile, and lowest in the higher wealth quintile. While poverty has declined across social groups, among the marginalised populations, the share of population in higher wealth quintile has changed comparatively at a slower pace (Fig. 1).

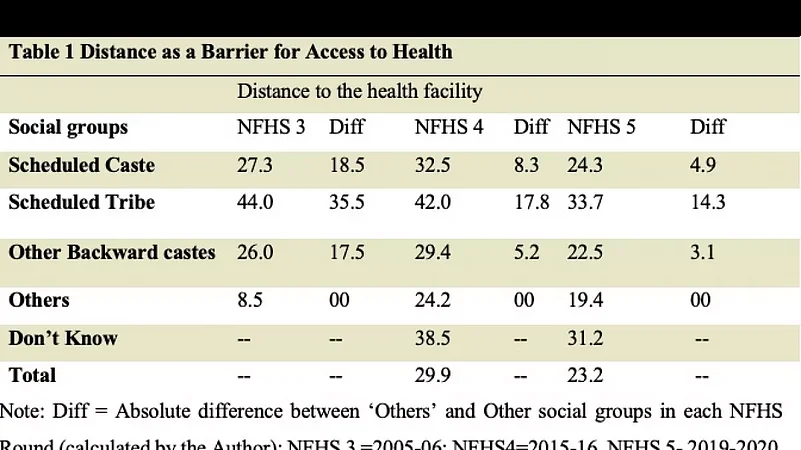

They are comparatively more disadvantaged in terms of health indicators. Access to health facilities is once such indicator. Distance as a barrier to accessing health care has reduced over the period of time, but the difference between the marginalised and the privileged groups has remained persistent (Table 1). Inequality has significant impact on health outcomes.

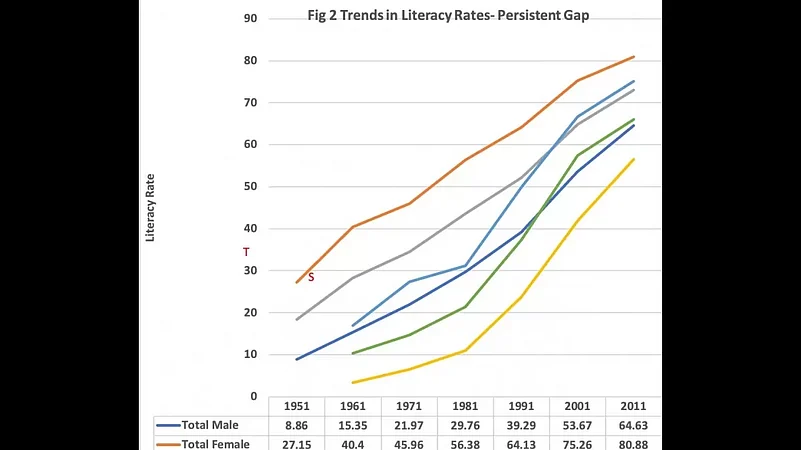

Social environments that are less polarising, are less likely to undermine one's sense of self, less likely to produce social conflict, and more encouraging for the development of skills and abilities; and are likely to improve the general health and welfare of the population. Literacy levels too have increased over the time, but the gap between the vulnerable and the privileged groups continues to exist (Fig 2).

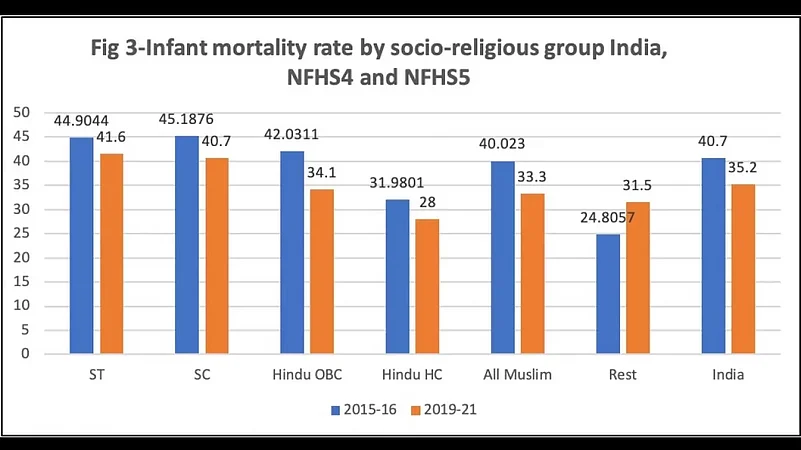

It is often contended that caste cannot be the cause of these variations in nutritional status. They result from socioeconomic factors like mother's education and household wealth, among others. However, the national level data on mortality suggests that children of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Muslims are more likely to have poor health than the children of the privileged groups (Fig 3).

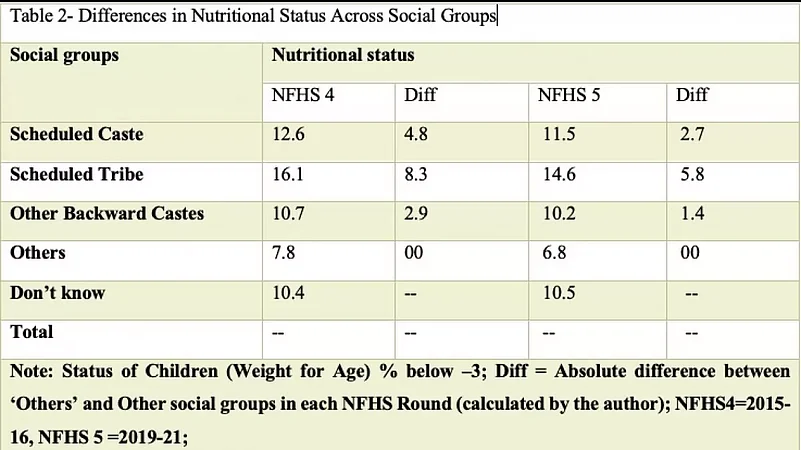

Prevalence of undernutrition among the children across social groups has been favourable to the privileged. The Weight for Age % below –3 SD reflects that while the share of children as well as the difference between the privileged and the marginalised groups has reduced from NFHS 4 to NFHS 5, it is noteworthy that despite various programmes including the largest feeding programme, Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) to the much-highlighted Poshan programme, the nutritional gap remains (Table 2).

Thus, there are evidences of socio-economic and demographic factors influencing health. Social identity such as caste is one of the most important social determinants of health and call for addressing all form of barriers to accessing health care. Disparities in health between different social groups are the function of unequal way in which the determinants of health are distributed.

Beyond physical and mental health, inequality has far reaching consequences on shaping the life course of individuals and self-worth of the groups. The Scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and occasionally, other backward castes are socially disadvantaged groups more likely to live in unfavourable conditions and are consequently more susceptible to illness. Their health condition and service utilisation patterns provide insight into their social exclusion as well as the relationships between poverty and health.

(Sanghmitra S Acharya is Professor and Chairperson Centre of Social medicine and Community Health School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University.)