“Janeu-dhaari Hindu.” Words that hiss with an anachronistic charge when spoken as an assertion, like some monster of the deep suddenly looming into view, and more starkly ironic when uttered by a spokesman of the Congress, which swears by secular progressive politics, unlike the Sangh parivar. Some would say it was true to form as all so-called secular parties are embedded in the old caste matrix one way or the other. And the Congress was reflecting its own inner biases, which all allegedly savarna-inflected parties pretend don’t exist.

In the process, a few curious things happened. A question of religion had unwittingly been deflected into one of caste—both factors brought into play, helped along by a few remarks about Aurangzeb, around the time Rahul Gandhi was about to take over as Congress chief. And against the backdrop of the Gujarat polls, where both caste and religion are fraught with meaning and consequences.

But why would MLA Randeep Surjewala, a former Haryana minister’s son, who usually chooses his words carefully like the lawyer he is by training—and yes, a Jat, who should have no great reason to espouse Brahminical anxieties—evoke the spectre of a thread-wearing Hindu? Why would he help the very symbol of caste oppression flowing from Manuvaadi attitudes hug the spotlight as a factor in India’s democracy, which has, ironically, been pitched—going by the letter and spirit of the Constitution—as a countervailing force to those attitudes?

One part of the answer: it was a Freudian slip, made in the heat of chasing political expediency. (Recall, in the same Gujarat campaign, the Congress is keeping a safe distance from anything overtly Muslim.) The other part trails off beyond the live political field of the day to a dynamic social history of over a century, where the janeu acquires some variable meaning across the landscape.

The trigger itself came via a minor controversy at Somnath temple, where Rahul’s name had apparently been entered in a visitor’s book for non-Hindus. It made the Congress walk right into the BJP’s trap. Perennially defensive about Rahul’s “credentials” in a polity that answers more and more to nativist themes, Congress spokespersons panicked. Soon, they were releasing old images with Rahul bearing obvious markers of Hinduism, or in ritualistic poses. Surjewala, though, outdid the rest. “Rahul Gandhi is not only a Hindu, but a janeu-dhaari Hindu,” he said at a hasty media briefing. That non-janeu Hindus are a lesser category is an obvious implication—and disastrous for the Congress’s claim to an egalitarian worldview.

Did Surjewala fumble in his eagerness to return serve, revealing more than was probably intended? The “not only/but” emphasis on janeu-dhaari almost exults on the Gandhi scion’s Brahmin background. “An attempt to take on the BJP at its own game turned out to be a shameful mistake,” says a disappointed Congress leader. “Instead of celebrating the diversity Rahul represents, the spokesperson chose to accentuate the janeu.”

Congress general secretary Janardan Dwivedi distances himself from it: “Main nahin chaahta koi Bharatiya dadhi, choti, janeu, veshbhusha ya kisi aur prateek se pahchaana jaye. Vah apni yogyata, gun aur karma ke aadhar par samaaj mein apni jagah banaye aur samman paye. (I don’t want that any Indian be identified by outward symbols. It’s qualifications, attributes and work that earn respect).”

Other party leaders, who believe the Congress must maintain its distinct identity and not play its old soft-Hindutva game, are squirming at suggestions that it comes off as a poor man’s BJP. Finance minister Arun Jaitley, especially, enjoyed taking a dig at Congress’s new-found Hinduness after Rahul’s Temple Run (he has already visited 21 temples in Gujarat). “If someone wants to mimic us, I have no complaint. But why would anyone prefer a clone to the original?” Jaitley asked.

When Rahul said he and his family are ‘Shiv bhakts’, but their faith is a personal matter, it left partymen unsatisfied. “If it isn’t for political mileage, why talk about being a Shiv bhakt?” asks a Congress leader. In the run-up to the UP polls, too, Rahul had visited Hanumangarhi temple in Ayodhya. The saffron stole he posed with had Ram emblazoned all over it. Earlier, he had trekked to Kedarnath. Surjewala had told Outlook then too that the Gandhis are Shaivites.

Apoorvanand, who teaches Hindi at Delhi University, feels Rahul was at least being more accurate and subtle in describing himself as a Shiv bhakt than parties that accuse rivals while bowing to powerful blocs. “His messaging was towards the Shaivite tradition, thereby bypassing both Jawaharlal and Motilal Nehru. He sought a connection with an older tradition in Kashmir, which he is entitled to.”

Surjewala insists this was the only aspect he intended to highlight—the personal and often overt religiosity of old Congress figures. “Indira Gandhi wore rudraksh beads. Mahatma Gandhi’s favourite bhajan was Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram…even his last words were ‘Hey Ram’. Does this make them bigots?” he asks.

But this invoking of the old Congress brand of Hinduism, whether spiritual like Gandhi’s or opportunistic like in the post-Indira phase, skirts the symbolic force that a janeu carries in what is still a deeply unequal society—and the abhorrent implications in a party citing it. It also does a poor job of explaining the varying meanings this symbol has across specific geographies. For one, the practice of thread-wearing (and who does it) adheres more to the canon in the eastern belt—the traditional three varnas do it—and things tend to get more fluid in the west.

Part of the irony is that it’s Surjewala who let this chance slip by to offer a more granular explanation. To anyone familiar with the recent history of Haryana, ‘janeu-dhaari’ would have denoted just about any practising Hindu. The Arya Samaj, since the late 19th century, has been conducting its own version of the thread ceremony for all castes, even for women, as a way to supplant the Brahmin’s hold over the ritual and everything it symbolises.

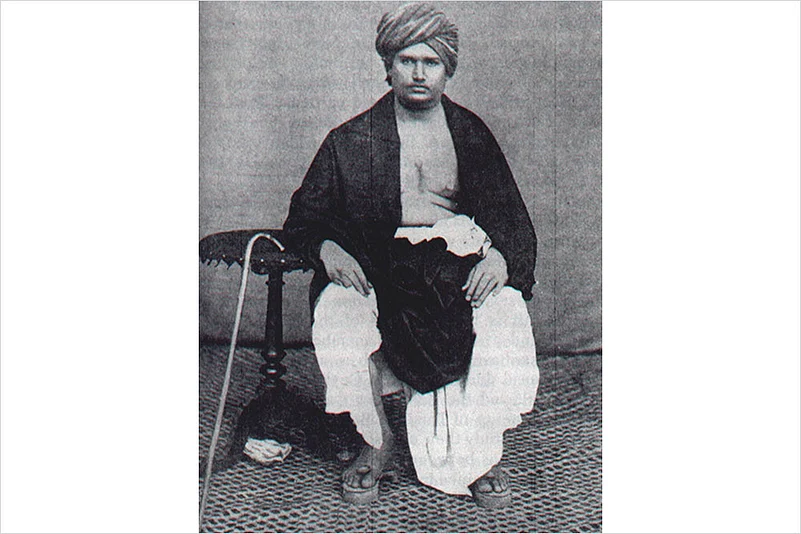

Dayanand Saraswati, founder of Arya Samaj, which conducts the thread ceremony for all castes

“The Arya Samaj movement was about breaking Brahminism. After Maharishi Dayanand, every human was entitled to the janeu, including women of any caste or religion,” says social activist and Arya Samaj figure Swami Agnivesh, who found Surjewala’s remark annoying, as the ‘janeu-dhaari Hindu’ category does not exist even in Arya Samaj lexicon. “Hearing Surjewala reminded me of a trap. The BJP laid a trap and the mouse walked right into it.”

In a way, Surjewala detracts from much of what happened in his state and around since the late 19th century. He also negates some of the ancestry his party can lay claim to. There is a tale, perhaps partly apocryphal, of how Bhupinder Singh Hooda’s grandfather, a colonial-era jaildar, strode into a Jat panchayat and vowed he would ensure the Arya Samaj drive to liberalise the janeu tradition continued. “Brahmins had terrified the Jats into believing that if they wore a janeu, it would invite floods, pestilence and disease. Hooda senior stuck to his stand despite community pressure,” says historian K.C. Yadav. Yadav cites an early 20th-century mutiny in the Jat regiment in Bengal and how it was quelled by a terrorised British establishment. “The British decided to designate all ‘janeu-wearing’ Jats as Arya Samajists and delisted them. That’s how they kept Jats out of the army for a good few years,” says Yadav.

On the back of this tradition comes Surjewala’s rather bland remark. He could have instead talked up those Hindus who asserted their right to liberalise an ancient tradition. Today, to say Rahul is a janeu-wearer makes it clear to listeners that Surjewala is resting his argument on presumed Brahmin superiority. “The so-called secular parties say their rivals practise casteism, but look today at where they kneel,” says Apoorvanand. “The BJP is happy with Patidars, Dalits and OBCs who side with it. But when they switch over to the Congress, it becomes casteism.” So savarnas still set the narrative, while courting other caste groups—and the seculars are also-rans in the game. In effect, savarna feelings thrive on all sides within this competitive space, the DU professor points out.

“There is no such term as ‘janeu-dhaari Hindu’. Certain symbols are employed as a matter of caste pride,” says sociologist Anoop Kumar Singh of DAV College, Kanpur. “Mayawati built statues and praised the valorous actions of Dalits as a form of Dalit assertion. Caste symbolism is reproduced in the age of mass culture, sometimes to establish writ.” He sees the ‘janeu-dhaari’ remark as “Rahul’s compulsion” at a time when “one does not even know if he is a Hindu”.

The reduction of the janeu to a mere symbol owes to its shifting meanings even within the Brahmin space in modern times. Of the rituals that socially construct a Brahmin, the upanayana is a core one. Even today, a Brahmin marriage would not be possible, outside a court, minus a symbolic thread ceremony. The world around the ritual may have undergone a sea-change, so its utility as a marker has become more acute. Says Ashish Saxena, Allahabad-based sociologist: “It’s worn today only by Brahmins and Kshatriyas. It marks their identity and is recognised as such by others. It was banned for the other castes.”

Yet in UP, as in Haryana, there are fascinating variations: the Vaishyas of western-central UP often wear the thread, which shows up not just as a burden of tradition, but also as an influence of the freedom movement, the Arya Samajists and the growing appeal of a secular education, which came hand in hand with urbanisation.

“My father Hargulal Gupta was a freedom fighter, very spiritual and strict about the rules of human conduct. He organised the ceremony, common among Vaishya families at the time, driven by the desire to educate us,” says Dr Vishesh Gupta, sociologist at Maharaja Harishchandra PG College, Bareilly, who went through the upanayana as an 11-year-old with his brothers and other relatives. The kids were then barred from reading Gulshan Nanda’s pulp novels, discussing romantic matters or watch films. To break these rules, it was believed in those days of Gandhian austerity, was to reduce the thread to “mere show”. That’s why Gupta discarded it beyond young adulthood.

“It comes with a series of precepts to internalise—this I could not do once I left my village and went into the city,” says Gupta. “We are neither Hindu nor Muslim, nor have a caste at birth.” Those identities are granted through ritual acts and, theoretically, these doors are open to everyone on all sides. “Like the Sikh’s amrit chhakna ritual, the thread is a way of internalising darshan, to synthesise what is human by coming close to god,” he says.

In the 1960s and ’70s, as secular education and urbanisation spread, the janeu came to be associated with a “backward society” and the ceremony underwent a limited liberalisation. “How to make a good citizen became the concern of all secularising movements, even those working within the tradition of sanatan sanskara,” says Ravindra Bansal, who also teaches sociology at the Bareilly college. One such force was the Arya Samaj, which, within the first few decades, had Jats referring to Brahmins disparagingly as “Pope”—a person with pomp and ceremony but who does nothing useful.

Yadav feels Surjewala’s reference carries at least a fraction of that memory. “His statement is not being seen in the proper light. In the Haryana tradition, ‘janeu-dhaari’ is better constructed as a practising Hindu than as a Brahmin.” Apoorvanand, however, counters this. “Jats once looked down upon Brahmins, but sanskritisation has changed that. They don’t hate Brahmins now, but claim they have at least become part-Brahmin,” he says. “They know they would not have got this if the shastras had been followed. It’s an agreement or compromise forged among Hindus.”

Today, the doors of secular education are open to all. “That is precisely why only Brahmins and Kshatriyas wear the thread today. It’s a way to show off, with no internal change associated with the thread. Nobody wants to follow its tenets,” says Bansal. That the symbol persists, in its hollow-at-the-core version, gives impetus to casteism and sets off all sorts of complicated responses. Lucknow University recently had to withdraw a course on Hindu rituals because admission to it was not limited to Brahmins, recalls Bansal.

This sectoral assertive tone plays out even as Brahmins internalise the ‘backward’ taint. “If a man twirls the janeu around his ear while going to the toilet now, people around will laugh and say, ‘What a backward man!’,” says Pradeep Johari, who teaches sociology at Moradabad in UP. Shame and assertiveness hand in hand. Apoorvanand, himself from the Panda class of Brahmins in Bihar, says, “Nobody has given it up. It’s culture, they say, but caste gets perpetuated in the name of culture.”

It’s against this dynamic context that Surjewala’s blunder has to be read. He accuses the BJP of stooping to “the lowest levels and hatching a conspiracy” for political ends. “All senior BJP leaders like Narendra Modi and Amit Shah are trustees of the Somnath Trust. It was their hoax,” he says. “They are responsible for the forgery in the register to divert attention from the real issues that plague Gujarat—the Patidar agitation, GST, unemployment, spiralling crime graph and inflation.”

But why not just say that, instead of invoking a hoary symbol? He says it was only to assert that Rahul is a Hindu. “We never raise the issue of faith. By forging the register, the BJP made it into an issue. I reacted only when the BJP questioned Rahul’s faith,” Surjewala says, adding that for the next Congress president, the tricolor is the biggest religion…“rashtra-dharm”.

Claiming to take pride in belonging to Kurukshetra, the land of Bhagavad Gita, he says, “I believe in the Bhagavad Gita’s teachings and there is no contradiction there with the idea of India. India is all-encompassing. It is vasudhaiva kutumbukam.” Perfectly pitched soft Hindutva, one could say—but the symbol placed at the heart of it, deliberately or ‘innocently’, is not an empty one. In the collective lexicon of millions of Indians, it’s freighted with the memory of social apartheid.

***

Randeep Singh Surjewala Doesn’t Even Have A Decent Defence

Why did you refer to Rahul Gandhi as a janeu-dhaari Hindu?

The BJP has stooped to the lowest level. They forged the Somnath temple register and raised the issue of Rahul Gandhi’s faith. I just pointed out their hoax.

But why the emphasis on janeu-dhaari? Wouldn’t just ‘Hindu’, without qualifying it, have sufficed?

The BJP is raising issues of faith by talking about Aurangzeb and other Mughals. We are not raising these issues. Faith is a matter of personal belief. For Rahul Gandhi, the country and the national flag are the highest religion.

You walked into the BJP’s trap....

The BJP is raising issues of faith to divert attention from real issues. They don’t want any debate on issues that matter—the Patidar agitation, GST, inflation and unemployment.

By Bhavna Vij-Aurora and Pragya Singh