This story was published as part of Outlook's 21 October 2024 magazine issue titled 'Raavan Leela'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

There was always a kind of sadness that lingered after the effigy of Raavan turned to ashes. His name Raavan means a ‘bluebird’ in the Gondi language. And his own story got lost in the politics of appropriation meant to serve vested interests. This includes those who assert that the king vanquished by Ram, another mythological figure who has almost become a historical entity, exists in a country that has seen a surge of Hindutva since the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1992 and the consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya earlier this year.

But the Ramayana isn’t a story about the victory of good over evil. It isn’t even about a war that established the kingdom of Ram and demolished Lanka, which was believed to be invincible. There is a type of violence inherent in that kind of a plot where one must be a hero and kill the other and the effigies that are burnt to commemorate that murder.

The Ramayana is a story about a tragic flaw that leads to tragedy. In this case, it revolves around the events that unfold after Raavan abducts Ram’s consort, Sita, to avenge the mutilation of his sister, Surpanakha, by Lakshman, Ram’s brother and the exiled king of Ayodhya from northern India.

The Ramayana is also a story of women who suffered at the hands of men. Like Sita, who was first taken away and then, asked by her husband to take a chastity test.

It is also the story of the cultural interaction and the cultural domination of the Aryans over the non-Aryan culture, where ultimately, the latter are subjugated and integrated into the Aryan cultural fringe.

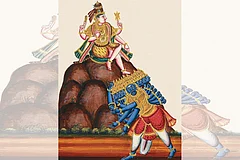

The Ramayana is the story of Raavan, the anti-hero whose many dimensions have resisted the imposition of a singular narrative of him being a demon king who was evil.

The Ramayana, an epic saga of so many characters, whose lives and fates are intertwined and who are all seeking redemption from their destinies and themselves, is a story that has changed the political landscape of India and more so, in a very reductive form.

Outlook examines Raavan as we prepare to once again burn the effigies of this misunderstood king who embodies the internal dramas of a man grappling with the conflicting forces within his own mind, where the real struggle is with oneself, not with anyone else.

Perhaps, that’s why Ram, as one folklore suggests, said that when the war is over, there is no enemy or enmity.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Raavan, the musician, the sage, the administrator, the human and the warrior, is a character who deserves dignity and not burning.