This story was published as part of Outlook's 21 October 2024 magazine issue titled 'Raavan Leela'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

About 170 km from Punjab’s capital, Chandigarh, lies the small town of Kapurthala, where every Dussehra, a group of young men wear black armbands to protest against “Raavan Dahan”, the customary practice of burning effigies of the 10-headed “demon king” from the Hindu epic Ramayana.

Lakhbir ‘Lankesh’ is usually at the forefront of these protests. He belongs to the Scheduled Caste (SC) Valmiki community that claims descent from the legendary author of the Ramayana and heads a civil society outfit called ‘Ravan Sena Bharat’. For Lakhbir, Raavan is a “Mahatma”.

“He is the ishth (patron deity) of our community,” he asserts, adding, “On Dussehra, Dalit and Bahujan groups in the region come together to mourn his death.”

Lakhbir feels that the annual dahan (burning) of Raavan is an unnecessary ritual meant only to concretise the “Brahmanic version of Ramayana based on interpretations by the dominant classes and castes that leave out the marginalised”. Adherents of Raavan, like Lakhbir, feel that the ‘indigenous king’ has always been mistreated in popular retellings and adaptations of the Ramayana.

“Raavan is shown as the criminal, a nasty kidnapper and abuser of women. But he only did what he did to avenge his sister Surpanakha’s dishonour by Ram’s brother Lakshman,” he states, adding, “He (Raavan) never touched Sita and treated her with the utmost respect, despite keeping her hostage.”

Living near a Valmiki temple, Lakhbir grew up listening to priests recount tales from the Ramayana, specifically the version by Valmiki, the patron saint of his community.

Reminiscing, he recalls, “As children, some of us used to perform ‘Valmiki-Leela’ as part of travelling shows. I even wrote a play.” The stories they depicted differed from those in Ramanand Sagar’s popular television adaptation. They focused on the Uttara Kanda, the last book of the Ramayana, which details the upbringing of Ram’s sons, Luv and Kush, in Valmiki’s ashram. While researchers assert that Valmiki was not the author of the first and last books of the Ramayana, Lakhbir notes that they (his group) favoured the Uttara Kanda because it features Valmiki himself and provides critical insight into the complexities of Ram and Raavan and the interplay of good and evil.

The Bala and Uttara Kanda, interpreted as the epic’s prologue and epilogue, respectively, carry lasting political implications. Scholars like Wendy Doniger, an expert on the Hindu mythology, suggest these chapters were added later, when Vaishnavism was firmly established, with Vishnu as its progenitor. It is only in these two books where it is explicitly stated that “Ram is god, that Vishnu was persuaded by the other gods to take the human form and kill Raavan. Ram’s story as god later becomes a central part of Vaishnava bhakti as versions of the Ramayana appear in different languages across the subcontinent and beyond,” Doniger notes in her book Uttara. In Uttara Kanda, Raavan’s cursed and demonic nature is reinforced through tales like Vedavati’s prophecy of a woman causing his downfall, Rambha’s efforts to protect women from him and predictions of monkeys annihilating his clan.

Doniger wonders why the “Uttara Kanda is so anxious that Ravana’s actions and his death be so utterly overdetermined. Could it be because the middle books of the Ramayana hint at Raavan’s nobility, his majesty?”

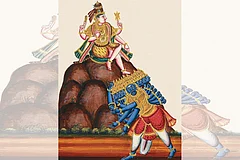

Raavan in Subaltern Imagination

Raavan worship is as old as the worship of Ram, especially in south India. He also resonates among sections of the subaltern, including the Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi community movements for identity and political assertion.

The Gond community in Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand views Raavan as a Gondi king and environmentalist, celebrating Raavan Mahotsavs during Dussehra festivities across India. Gonds in Gadchiroli worship Raavan’s son Meghnad. Adivasi communities like the Bhil and Koli—found across central, Deccan and south-western India—also venerate him, as do some caste Hindus in Bisrakh, a small town on the outskirts of Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, believed to be his birthplace. In Maharashtra, the Maharashtra Rajya Adivasi Bachao Abhiyan, led by Ashok Bagul, advocates against the burning of Raavan effigies, emphasising his representation of the downtrodden. Bagul’s 2019 movement united various tribes to honour Raavan, echoing similar protests in Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh. Activist Laxman Bagul from Dang, Gujarat, notes that for backward, Adivasi and moolnivasi (original inhabitant) communities, the Ramayana offers little solace.

“The killings of Shambuca and Vali, the stories of discrimination against Ekalavya, Karna and the fact that the story is of a ‘warrior caste’ ruler who is actually a God incarnate and his council of Brahmin ministers, make it rather non-inclusive of the marginalised,” Bagul states.

In Dang, festivals like Dongarya Dev Pujan feature the recitation of ‘Dangi Ramkantha’, a local version of the Ramayana with significant variations, particularly in its portrayals of Ram and Raavan. In Nashik, the Bohada mask festival provides another opportunity for Adivasi communities such as the Mahadev Kolis, Malhar Kolis, Dhor Kolis, Katkari and Warlis to come together in celebration. During this festival, they honour not only Raavan but also other ‘asura’ characters, including Mahisasur, Bakasur, Hidimba, Narsinha and Dait.

Hindu mythological narratives, rooted in Vedic literature, often embody a “nationalist” character that plays out through an epic conflict between the ‘Gods’ (deva/devta) and demons (asura). Proponents of subaltern reinterpretation and deconstruction of these myths frequently identify the subaltern with the “asura”, transforming villains into heroes, or at least anti-heroes. In this sense, the “demon” becomes a symbol of the oppressed rather than the oppressors. Central to these revisionist narratives are mythic episodes from the Mahabharata and Ramayana, which highlight the cruelty of Hindu gods toward the asura characters.

Dalit and subaltern movements in India have often been shaped by dominant cultural representations and scholarly theories, leading to countercultures of political and self-assertion. This is evident in Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi student identity politics. In 2013, students at Osmania University’s English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) faced a backlash for celebrating “Asura Week” on the campus to promote subaltern Dravidian culture. The event included face-painting, art installations depicting Surpanakha, open canvas sessions for artworks on ‘Memories of Oppression’ and discussions on resisting dominance through cultural articulation.

In 2015, students in Andhra Pradesh ruffled right-wing groups by “celebrating” Diwali in mourning for Narkasura, another “asura” from the Hindu mythology, who was killed by Krishna and Satyabhama during an epic battle coinciding with Diwali. In Goa’s Ponda, where Narkasura effigies are burned on Diwali, local artists from the backward castes view the “demon” as their hero. “The annual Narkasura floats (or parades) are our financial mainstay. Thanks to Narkasura, we earn enough to sail through six months,” one artist jokes.

Such inversions of myths attempt to construct a more inclusive or Bahujan identity, encompassing not only ex-“untouchables” but also other marginalised ‘backward’ castes, tribes and religious minorities, notes Kristina Garalyte, a Lithuanian researcher and author of Subaltern Autonomy: Dalit Students’ Identity Politics in India.

Post-colonial theorist Ashis Nandy’s works on humiliation as a psycho-social state highlight that humiliation functions through mutual consensus on its meaning systems that could be reversed through rejection and inversion. This could explain why some Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi identity politics and counterculture movements focus on deconstructing and re-signifying the meaning systems within the Hindu nationalist discourse, leading to changes in self-perception, as Garalyte notes.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

In this context, rejecting the notion of Raavan as a villain signifies a persistent need to challenge the dominant narrative while remaining part of it. As Lakhbir puts it, “Raavan worshippers are not against Ram. We just want Raavan to get the respect he deserves. Ram is a hero, but Raavan is not the villain.”

(This appeared in the print as 'The King Of Counterculture')