The police. The very mention of the word could touch off conflicted responses. Frustration would be a universally shared feeling. Their presence is likely to bring on a sense of fear, rather than security. More troubling, however, is their absence—the patterns of where they choose not to be. This week brought a fresh instance in the controversy around Bollywood film Padmavati. The aggressive, violent protests by Rajputs have an unstated enabling factor: the silence of the police.

That hate speech could fill the airwaves with such impunity is a sign of how feudal attitudes and caste structures shield dominant groups, allowing them to use the state and the police to establish their writ. Contrast the role of police in two recent cases. One relates to Dalits, in UP’s Saharanpur. And the other is of the Rajputs, who overran two fort-palaces in Rajasthan, denied the public access to these popular tourist destinations and vandalised a theatre.

The leader of a caste outfit called Shree Rajput Karni Sena even threatened to disfigure top actress Deepika Padukone, who plays the lead role in Padmavati. An array of politicians too promised exorbitant “rewards” to “behead” Deepika and murder producer-director Sanjay Leela Bhansali. While Maharashtra has ramped up protection for the two, no police force has yet tried to arrest the rampaging clansmen.

The police in Rajasthan, where the protests began, have not tried to detain Karni Sena members. The rabble-rousers are roaming the country, delivering provocative speeches. They have arm-twisted authorities into delaying Padmavati’s release, while disrupting everyday life in Rajasthan and elsewhere. It’s almost as if they are the law.

In fact, that isn’t too far off the mark. Rajputs, with their long history of ruling the region, not only dominate Rajasthan politics, but evidently also consider themselves entitled to make their writ run. “We Rajputs worship Queen Padmini and find this film offensive. The director says Padmavati is based on history, but we dispute his facts. So why should we let this film be screened?” asks Karni Sena leader Mahipal Singh Makrana. And then the clincher: “Why would the police want to take action against us? They are from Rajasthan, not outsiders. All of them know we are fighting for the dignity of our women.”

The self-conscious ‘traditionalism’ is a kind of default politics. What makes it worse is that the police wouldn’t have been silent observers if they didn’t implicitly share this politics. The Karni Sena propagates a notion of Rajput womanhood neither in sync with reality nor compatible with the laws. Yet, Makrana speaks boldly not just for Rajput women, but for all cinema-goers. His biggest grouse is how Deepika’s character does not follow the discriminatory practice of wearing a veil. “Rajput women work in modern offices, but have not discarded their traditions. Royal women did not dance the way the film shows our queen. Now there will be no discussion on this,” he says. “We know what Rajput women are like—not filmmakers.”

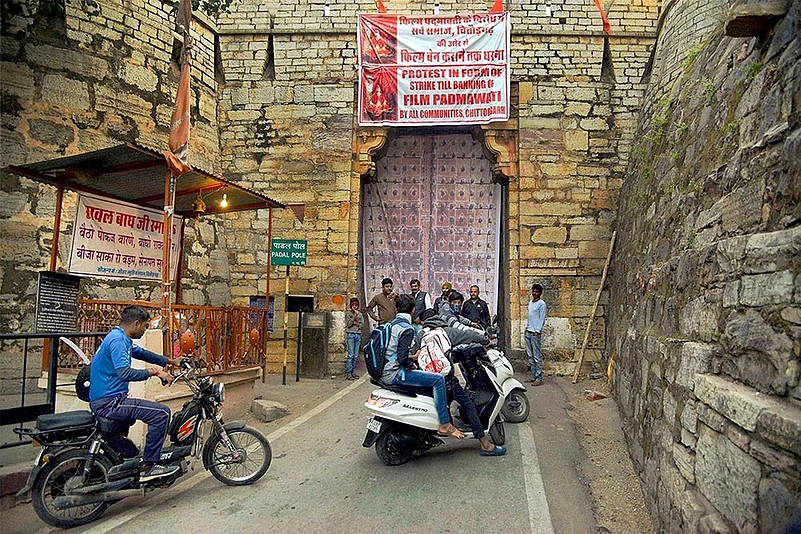

In the assessment of the police in Chittorgarh (which faced the first serious demonstration), these words and actions were perfectly legitimate and justifiable. On Friday, around 1,000 Rajputs besieged the Chittor fort where there is a 19th century reconstruction of what was claimed to be “Rani Padmini’s palace”. One man even fired a shot from a gun. The police did slap the Arms Act on the trigger-happy man, but did not arrest him.

“He fired a shot in the air, but not with criminal intent,” says Rajan Dushyant, Additional Superintendent of Police, Chittorgarh. “It was only an air gun, commonly used at celebrations. It only makes a sound. They held a peaceful gathering. They came, delivered speeches and left.” Arrest? The matter “is under investigation”, the ASP says. He does not think the gathering was disruptive either: “Tour guides had informed tourists beforehand, so no tourist came to visit Chittor fort on Friday.”

Rajput protestors lay siege to the Chittorgarh fort in Rajasthan, demanding a ban on the movie Padmavati

In stark contrast, witness how the police acted when Dalits came into conflict with Rajputs this summer at Shabbirpur in Saharanpur. No defusing the anger, no placating ‘wait-and-watch’. Dalits, the most lowly and poor in this region, have virtually no influence over state power, and this is reflected in how the law treats them.

The incident at Shabbirpur was triggered when Rajputs led a procession to extol Maharana Pratap. Local Dalits apparently demanded that the procession be a little less noisy. This ended in a skirmish. After a small number of local policemen dispersed the crowd, one injured Rajput died. Then, hundreds of Rajputs regrouped and torched 20 Dalit homes. Several police vehicles too were damaged in the mayhem—as a symbol of the state, it is frequently the target of protesters. Yet, it is not a neutral element: a broad complicity in social power structures shows up again and again.

The whole region was already fraught with ‘tensions’ for some time, after a series of Rajput-Dalit and Dalit-Muslim clashes. Rajputs were freshly feeling a sense of renewed assertion after Yogi Adityanath, a fellow caste man, became chief minister. A section of Dalits, on the other hand, were feeling dispirited by a sequence of terrible electoral losses that came the way of Mayawati’s BSP. It was against this backdrop, and reflecting this fraught politics, that a new Dalit organisation, Bhim Sena, and its chief Chandrashekhar came into focus. How the police acted to neutralise him is an exact inversion of how it is now acting in Rajasthan. The young activist immediately faced arrest for having mobilised Dalits.

Chandrashekhar’s charisma and powerful counter-assertion led many to see a subaltern hero. Some predicted he could one day challenge both the BSP and the BJP. The law soon took special interest in him. The police, ‘intelligence reports’ and politicians labelled him ‘Naxal’, ‘anti-national’, ‘violent’, even ‘terrorist’. The chatter stopped only after his arrest in June.

Police thrashed protestors after a school student’s murder in Gurgaon

On November 9, Chandrashekhar was given bail because the cases against him carried no specific charges. However, even before he could leave Saharanpur jail, the police charged him afresh. This time, it was under the National Security Act (NSA)—so he cannot even apply for bail for a year.

“The way the police acted only shows bad intentions,” says Meerut-based Dalit ideologue Satish Prakash. “In a democracy, everybody has the right to express himself. If someone gets frustrated when nobody listens to him, naturally there are chances he will become aggressive. But if you ensure he never leaves jail, it implies you don’t want to tolerate dissent.” It is simply an action loaded with politics.

Police partisanship is not a new phenomenon, nor limited to Rajasthan and western UP. It just shows up in stark relief in areas strongly marked by the play of caste and creed. This lends weight to accusations that the police too share those traits and are deeply influenced by politics. The conditions for police work too are bad in these regions. Haryana, for instance, had only one policeman for 607 persons in 2016 and UP one for 537, according to the Bureau of Police Research and Development. The national average is one policeman for 519 persons.

A 2003 study by the Institute of Conflict Management (ICM) examined the frequency of transfers of superintendents of police (SP) to reveal another systemic rot. Even in 1947, the study finds, the average tenure for an SP was only a year and a half. Between 1995 and 2000, this slipped to 6-9 months across 73 districts. “In certain politically sensitive jurisdictions, say, the chief minister or some other top leader’s constituencies, the average tenure of SPs was three months or less. Afterwards, it improved—to roughly four months,” says Ajai Sahni, executive director, ICM.

SPs often form the first line of supervision for crime investigations and their highly unstable tenures indicate a kind of instability within the system. The study attributes UP’s transfer raj to “political instability, coalition governments, increasing politicisation at the grassroots, criminalisation of politics and the increasing role of caste in politics.”

It is perhaps hard to buffer an institution like the police entirely from politics, but professional standards have fallen too far in the Hindi heartland, say many serving and retired cops (and bureaucrats) who have worked in these states. They look upon the state of affairs with a sense of despair. “Investigation standards have declined in the last 15 years and the police are falling back on identity politics and money power more and more,” says Prakash Singh, former UP top cop. Singh once considered UP the most corrupt, but now thinks Haryana’s administrative system, including its policing, is “rotten to the core”.

He should know. In 2016, he led a one-man commission to probe the administration and police’s role during the Jat reservation agitation that had turned violent. His report indicts several IAS and IPS officers. “At first, the additional chief secretary (home) and the DGP were removed. Then the remaining senior officers mobilised their political godfathers and raised a hue and cry to discredit my report. The Khattar government, though an honourable exception to the usual Haryana politics, got cold feet,” he says.

Despite a high court intervention, all the state did was to act against some non-gazetted police officers and issue showcause notices to four each in the IAS and IPS. “Nothing substantive,” says Prakash Singh. He attributes this partly to “psychological factors” influencing policing—caste and money determining postings and promotions. “The solution is—don’t Yadavise the police in UP, or Jatise it in Haryana. Don’t follow an undeclared agenda.”

Prakash Singh estimates roughly 40 per cent of Haryana’s constabulary consists of Jats. So speculation is natural about its stance during the Jat agitation—particularly how investigation into alleged mass rapes at Murthal flopped. “There can be a detailed study of caste in policing. Politicians want people of their caste in police so that even after they leave office they have someone to help them.”

A confession allegedly extracted from a bus conductor was later trashed by the CBI

A big part of police training is indoctrinating recruits with the idea that their caste should not affect their job. In the words of retired IPS officer Gautam Kaul, they have to forget they are Jat or Ahir and not think they do ‘biradari’ work. Yet this is the dilemma constables face on the job. “Their roots are in poverty and, as cops, they oppress the same underprivileged class. They see their supervisor from the middle or upper class having vested interests, if not outright a party man,” he says. “The Supreme Court, in the Prakash Singh case, overlooked this aspect. There must be a public outcry for fair and neutral policing.”

Kaul is referring to a landmark 2006 ruling that laid the groundwork for police reform, but whose implementation has been sporadic. Yet, public faith in police is pretty low—as can be seen in regular demands for CBI probes. In the recent spate of cow-related mob lynchings, victims have regularly demanded CBI intervention.

These days Harsh Mander, former bureaucrat turned activist, has been touring Haryana, UP, Rajasthan, Gujarat and other states, visiting families of victims of mob lynching. He has noted a change in how the police respond to this category of crime. “In Haryana and UP, I notice the police actually acts as a direct attacker. Everywhere, I found open or tacit support among police for mob lynching. But here the police have become the lynch mob themselves,” he says.

Mander attributes this to the ‘ideological adjustments’ police make—or are forced into. “Today the police are increasingly the hard arm of the BJP leadership and their ideology. It is a cosy relationship. Haryana is the first state to start a cow protection force within the police. Once you divorce policing from professionalism and independence, you see such distortions,” he says. He studied Congress-ruled states as well and found they appeased fundamentalist elements among both Muslims and Hindus, for example, by introducing a slew of laws that are unfair to minority groups, but simultaneously failing to enforce them.

In Rajasthan, Pehlu Khan’s lynching invited much criticism of the police, especially for the way in which counter-cases were filed against the victims. Pehlu’s family has since appealed to the SC for justice. “They have no faith in the political class or government,” says Ajit Sahi, a former journalist who was recently part of a fact-finding team on the case. The team found that the police investigation had, in fact, “sabotaged” the case of the complainants. “A new FIR should be registered. The six named accused should be arrested. The VHP and Bajrang Dal activists, named in Pehlu’s dying declaration, should be investigated,” he says.

On February 22, 2016, Jat protestors went on the rampage in Murthal, Haryana, including alleged mass rape, but the probe is said to have flopped due to Jat dominance in the state police force

Even relatively ‘simple’ crimes—such as the recent murder of seven-year-old Pradyuman Thakur at Ryan International school near Gurgaon—can show up bias and the deep politics of caste. Vikram Singh, former DGP of UP, finds the Gurgaon police’s handling of this crime extraordinary, especially the “confession” of Ashok Kumar, the school bus conductor the police arrested. For, it contained every necessary ingredient of sections 299 and 300 of the IPC, which define murder.

“The poor fellow’s confession was—‘I saw the boy, I decided to kill him, I stabbed him, then he died’,” says Singh. “Every sentence matches the definition of ‘murder’ in the IPC. The police picked up a hale and hearty man, had him hobbling in three days, got an extra-judicial confession and a barely literate man narrated his ‘crime’ like a parrot.”

Early in this probe, Pradyuman’s parents contacted Singh, seeking help and narrating their misgivings. “The parents had no faith in the police,” Singh says. Mohit Verma, Ashok’s advocate, adds, “The police tortured Ashok using third degree to get his confession. It’s nothing new for Haryana. It happens all the time.” That Ashok is a Dalit, of course, is no incidental fact.

Mander, whose first reaction to Ashok’s arrest too was that a poor man is being made a scapegoat, says: “People have come to believe that the police in these states only hang people upside down and beat them. That there’s no scientific investigation.”

“People have faith in the CBI because they are seen as specialists, free to function in a transparent way,” says Ankur Otto, project officer, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI). “Even a common man knows that to hold someone guilty you need witnesses, circumstantial evidence and forensic data. Hence, in the Ryan case, everyone wondered about the basis for arrest.”

“I will only say I want to give everybody a chance to eat their own words,” says Sandeep Khirwar, police commissioner of Gurgaon, who has come under fire ever since the Ryan case was transferred to CBI on public demand. The CBI quickly unearthed a new possible killer, a 16-year-old fellow student from a well-placed family of the locally dominant Yadav caste (Yadavs of Haryana are well-heeled and were the rulers of Rewari, next to Gurgaon). The theory is: he wanted exams postponed, as also a parent-teacher meeting. “Everything is still open to investigation,” Khirwar says. “Let the CBI probe conclude.”

The SC’s 2006 order that states should separate the police’s law & order and investigation roles is a critical idea. When the same policemen handle law & order and investigation, there is an inherent pressure to solve cases anyhow. Hence, forced confessions. “On paper, law & order is separate from investigation, but not in fact. When 30 per cent of legislators are jailbirds, why would they be unsparing towards a corrupt police? They want them to be pliable,” says Singh.

Haryana has created specialised units for “economic” and “heinous” crimes. “But this does not necessarily comply with what the SC wants. Scores of IPC crimes cannot be ignored because they are not ‘heinous’ or ‘economic’ offences,” says Otto.

The sense of justice not being done prompted people in Himachal Pradesh to demand a CBI probe into the ‘Gudiya’ rape and murder case. “It’s very important to pay attention to the word on the street because the buzz is usually on the right track,” says Abhinav Kumar, an IPS officer based in Chandigarh. “If public opinion is ignored, it creates lingering doubts, a sense that the wrong man has been caught. When the police do the right thing, this buzz always goes away.”