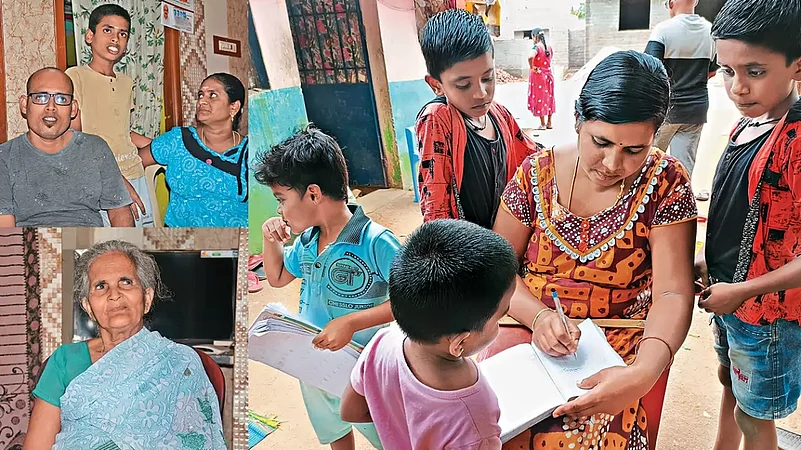

The pungent odour of a burning tire, the jarring echoes of gun shots and the grim sight of a partially-charred corpse lying in the middle of an empty street—70-year-old Theresa, exiled from Sri Lanka, is engulfed by a vivid array of emotions while recollecting memories of her homeland. Theresa, who fled to India in 1990 along with her family and now living in a rehabilitation camp in Minnur, Tamil Nadu, talks about her life—from the blissfully ignorant childhood to the disquieted adolescence and unsettled youth eclipsed by ethnic conflicts and civil war in Sri Lanka.

Theresa and her husband Samuel belong to Vavuniya district located in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka. They joined hundreds of Sri Lankan Tamils who fled the country following the civil war (1983 to 2009). Theresa, her husband and her two sons were accommodated in a refugee camp—which was later rephrased as a rehabilitation camp—in Minnur village in Ambur, the district bordering Karnataka. But the couple did not bring their only daughter, the youngest of all, who was left with other family members who remained in Sri Lanka. The trauma of war and the hardships of life in exile had taken a heavy toll on Samuel’s health; he passed away eight months after their arrival in India. Theresa’s sons, Jebaneson and Antony Raja, fled to Australia in 2013—illegal migration was the only way as both did not have citizenship of any country. That was the last time Theresa could see her children.

According to the Chennai-based Rehabilitation Commissionerate, the department responsible for the wellbeing of the Sri Lankan refugees in Tamil Nadu, there are 58,357 Sri Lankan Tamil refugees living in 106 camps in 29 districts across Tamil Nadu as of May 1, 2023; 10,269 are children below the age of 11. According to human rights activists working for the refugees, there are an equal number of people living outside the camps. They estimate that Tamil Nadu is home to more than one lakh Sri Lankan refugees living across the state—registered and unregistered.

‘Repatriates, Not Refugees’

Unlike other refugee communities in India, Sri Lankan Tamils have a unique claim that they are not technically refugees, but they have to be considered as repatriates. In the early 19th century, the forefathers of the present generation of Sri Lankan Tamils were moved to the island nation by the British to work in the tea estates. According to V Support, an organisation working for the rights of Sri Lankan repatriates, the Tamil people in Sri Lanka suffered racial discrimination and were denied citizenship when Sri Lanka got independence in 1948. The two pacts signed between India and Sri Lanka in 1964 and 1974 gave them the assurance that the Indian-origin Tamils would be given citizenship in both the countries—around 50 per cent of them in India and the rest in Sri Lanka. However, this promise was never fulfilled as the civil war broke out in 1983. All the piecemeal activities came to a halt and there was a huge influx of Sri Lankan Tamils to India since then.

“We believed we were refugees, but since the BJP came into power, we came to know that we are illegal migrants,” says Saravanan Nataraja, a refugee in Minnur camp. According to an affidavit submitted by the Central Government in the Supreme Court in 2019 (Ulaganathan vs Govt of India), Sri Lankan Tamils living in India are illegal migrants. Though the Tamil Nadu state government maintains the stand that they are not against the idea of granting citizenship, this decision rests with the Union government. “The status of a refugee would at least bring you some love and empathy, but being identified as an illegal migrant would always portray you as a potential offender,” says Saravanan.

What makes these people deprived of even the status of a refugee? India is not a signatory to international protocols regarding the welfare of refugees. India has chosen not to sign either the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, both of which have garnered an extensive number of signatories, totalling 140 countries, constituting an overwhelming majority. “Technically speaking, anyone living in India with no valid documents is an illegal migrant, not a refugee, because India has not recognised the refugee status,” says Kulaintha Swamy, an activist working for the rights of the Sri Lankan Tamils in India. Ironically, Sri Lankan Tamils living in various camps in India are eligible for documents such as Aadhaar card and driving licence. They are granted ration cards too. “Still they call us illegal migrants,” says Saravanan.

When it comes to Sri Lankan Tamils, even the celebrated Citizenship Amendment Act did not come to their rescue. “Why Sri Lanka was excluded from the purview of this Act?” asks Antony Arul Raj, another activist in Tamil Nadu. “If the Act was brought to provide asylum for people who are persecuted in neighbouring countries, there is no reason to eschew the Sri Lankan Tamils,” he says.

Repatriation is Impractical

A majority of Sri Lankan Tamils that Outlook spoke to expressed a strong reluctance to return to Sri Lanka. Given the option, they would prefer to remain in India and obtain Indian citizenship. Udayakumar, a resident of Minnur camp, explains, “Sri Lanka is a completely unfamiliar world to our children. The younger generation hasn’t even set foot in Sri Lanka and lacks any understanding of what it’s like there.”

“Over the past 40 years, more than 50,000 children have been born in India,” says Romeo Roy Alfred, a lawyer. “For them, Sri Lanka is simply a foreign country. Even for the older generation, who migrated to India, their roots are firmly planted here, as they are descendants of those who moved to Sri Lanka to work in the tea estates. They consider themselves as people of Indian origin.”

Romeo reveals that those who have been repatriated to Sri Lanka advice people not to make the same “mistake”. Granting citizenship to Sri Lankan Tamils in Sri Lanka has become entangled in legal complications and bureaucratic red tape. Moreover, racial discrimination persists even though the civil war has ended. The current financial crisis in Sri Lanka has only worsened the situation as even those who wanted to go back are having second thoughts.

Bleak Future

“A person with no citizenship is not eligible to apply for a government job; our children cannot appear for the common entrance examinations like NEET. The young generation disillusioned and they easily fall into the hands of drug peddlers,” says Saravanan.

Most Dravidian parties in Tamil Nadu have been historically sympathetic towards the Sri Lankan Tamils. There are initiatives to offer housing and financial assistance to registered Sri Lankan refugees who reside in camps. Under these initiatives, the head of the family receives Rs 1,000, the wife receives Rs 750, and each additional family member receives Rs 500 per month. This provides significant relief for the Sri Lankan Tamils who are living in dire conditions in the camps. However, there are no specific programmes targeting the education of children, apart from the general initiatives available to all residents of Tamil Nadu. The government is yet to address the pressing issues of rampant unemployment, alarmingly high suicide rates, and the prevalence of drug abuse.

What’s worse, the inmates of the camps must inform revenue officials if they plan to be away for more than 24 hours. Saravanan explains, “In the past, the conditions were stricter. We had to sign in the morning and evening every day in front of the village officer. Now, this rule has been relaxed.” Anyone visiting the camp, including journalists, is closely monitored by the Q Branch of the police in Tamil Nadu. In essence, the Sri Lankan Tamils, many of whom have Indian origins, live at the mercy of the State. They reside in a partially closed, partially open prison, lacking the same dignity as fellow human beings who were born and raised in India.

“We don’t belong here,” says Saravanan. “At the back of our minds, we always carry the burden of this thought. Therefore, we live like cowards. Even if I witness an accident, someone being lynched, or a clash between groups, I restrain myself and keep my distance, which goes against my conscience. But if I intervene and something goes wrong, I would be the easiest target because I belong to no country.”

(Edited by S S Jeevan)

(This appeared in the print as 'We Belong To No Country')

Shahina K K in Ambur, Tamil Nadu