Close on the heels of the Bengal Renaissance—the first of its kind in the country, hence called the “Indian Renaissance” as well—came the Kerala Renaissance. It has not received the same attention as the former because the scenes of action were mostly outside British India, in the princely state of Travancore. The two movements originated in different sections of the society and, therefore, acquired different characteristics. The Bengal movement was initiated by English-educated members of the upper castes and was largely confined to the upper strata. The originators of the Kerala movement, as also the one in Tamil Nadu that followed, were the intermediate castes, which the State has since labelled as Other Backward Classes. The Dalits, too, were at the forefront of the movement in Kerala in the early days and their active participation made it all-encompassing. Changes kick-started by this movement put Kerala ahead of the rest of India in education and public health and helped it achieve by 1970 social parameters comparable to those of the West.

The Kerala Renaissance was ignited by Sree Narayana Guru, a 32-year-old ascetic, who picked up a stone from a river bed and consecrated and installed it as a Shiva idol in a makeshift temple at Aruvippuram, 25 km from Thiruvananthapuram. He also put up a notice board with these words: “This is an ideal place where all live in brotherliness without caste differences or religious rancour.” That statement came to be recognised as the ultimate aim of the Renaissance. This was in 1888, barely two years after the founding of the Indian National Congress, which was to evolve as the spearhead of the national freedom movement.

The temple at Aruvippuram helped members of the ‘lower’ castes overcome the disability they experienced due to lack of access to Hindu places of worship, so orthodoxy was immediately up in arms, asking who gave Sree Narayana, a backward Ezhava, the authority to consecrate the idol—something only Brahmins were entitled to do. He told them what he installed was “our Shiva”. He later built more temples, not only in Travancore, but also in other places such as Dakshina Kannada—always at the instance of people who wanted their own places of worship. He told them to keep the temple doors open to all, irrespective of caste.

The idols he consecrated were not of Shiva alone. Other popular southern deities such as Subrahmanya and Devi also figured among them. In later temples, he replaced the idol with a mirror, sometimes with words like om, truth and dharma inscribed on it, to remind worshippers of the Upanishadic principle of “thathvamasi” (thou art that), embodying the Advaitic thought. He also indicated that they must build educational institutions instead of places of worship in the future.

Sree Narayana’s activities may seem to fall within M.N. Srinivas’s concept of sanskritisation, but, then, the deities he chose were of pre-Vedic origin. His temple-building activity prompted some to conclude that he was a Hindu sanyasi. But he dispelled the idea, saying he was ready to build places of worship for followers of other religions too.

On one of his visits to Kerala, Mahatma Gandhi had long discussions with him with the help of an interpreter. The transcripts, preserved at Sivagiri in Varkala, where the Guru had his headquarters, make interesting reading. “Does Swamiji know English?” asked Gandhi. Sree Narayana said, “No” and enquired if Mahatmaji knew Sanskrit. “No,” Gandhi replied. Thereafter Gandhi asked if Swamiji did not believe Hinduism was enough to attain salvation. At that time, the lower castes were converting to Christianity or Islam in large numbers to free themselves from the curse of untouchability, and Gandhi was keen to check the resulting erosion of Hindu ranks. Not satisfied with Sree Narayana’s answer that “any religion will suffice for salvation”, Gandhi repeated the question until the Guru said, “The Hindu religion, too, will suffice.”

Recently, Kerala celebrated the centenary of the Guru’s “No Caste” proclamation, issued shortly before he died. In the proclamation, he said he had transcended the caste and religion he was born into. Yet many, for whom transcendence of caste and religion is a concept beyond their comprehension, still try to put him in a religious pigeonhole.

C. Kesavan, an OBC leader, went on to become CM

In 1903, his followers formed an organisation and called it the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (society for propagation of the ideals of Sree Narayana) with the Guru himself as the president. Four years later, Ayyankali, who was fighting for the rights of Dalits, founded the Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham (association for protection of the poor). At this time, Islamic scholar Vakkom Abdul Khader Moulavi was campaigning for reform among Muslims. These visionaries were not English-educated, but their movements benefited from the educational efforts of Christian missionaries.

As the citadels of feudalism started crumbling under the movements’ impact, the upper castes initiated reforms in their own communities to protect their interests in the emerging new order. When political parties came up and held out promises of freedom and equality, the downtrodden sections that had been radicalised by the reform movements threw in their lot with them in the hope that they would fulfil their dream of an equitable order. With the beneficiaries of the old order dominating the main political parties, the transition to a new order, however, proved to be interminably long.

Politically, the Renaissance’s high point was the election of the CPI to power in Kerala in 1957. Various caste and religious groups soon came together to challenge the CPI-led government’s land and educational reforms, and the Congress party’s alignment with them paved the way for the feudal remnants to stage a comeback. For the next two decades, the state witnessed a tussle between forces eager to pull the state in different directions. A virtual consensus emerged by the early 1980s, and the social justice platform became the main casualty.

The Renaissance swept up a host of OBC leaders. C. Kesavan and R. Sankar of the Congress became chief ministers, while the CPI(M) informally projected the feisty K.R. Gowri as a CM candidate in an election, only to drop her and instal a trustworthy paternalist after winning. Since then the CPI(M) too has thrown up two OBC CMs.

The pioneer of the reform movement in Tamil Nadu was E.V. Ramasamy Naicker ‘Periyar’, who began public life in 1919 in the Congress, but quit the party six years later, dubbing it a tool of caste supremacists. He then joined the anti-Brahmin Justice Party. On becoming its president, he changed its name to Dravida Kazhagam. His Self-Respect Movement eliminated Brahmin priests from weddings and other ceremonies, while he promoted the use of Tamil to strengthen the Dravidian roots. Tamil Nadu has so far blocked all attempts to make Hindi the country’s sole official language.

Shortly after Independence, some of Naicker’s young followers walked out of the party led by C.N. Annadurai, resenting his marriage with a much younger Brahmin woman. They formed the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), which carried the movement forward using literature, cinema and theatre with consummate skill. Initially, they proclaimed an independent Dravida Nadu as their goal, but gave up the secessionist slogan when they sensed the possibility of coming to power in the state under the prevailing constitutional scheme.

The state Congress too underwent ‘dravidisation’, and K. Kamaraj emerged as its tallest leader. But the transformation came too late to prevent the DMK’s rise to power in 1967. Since then, the DMK and its breakaway All India Anna DMK, founded by movie idol-turned-politician M.G. Ramachandran, have alternated in power in the state.

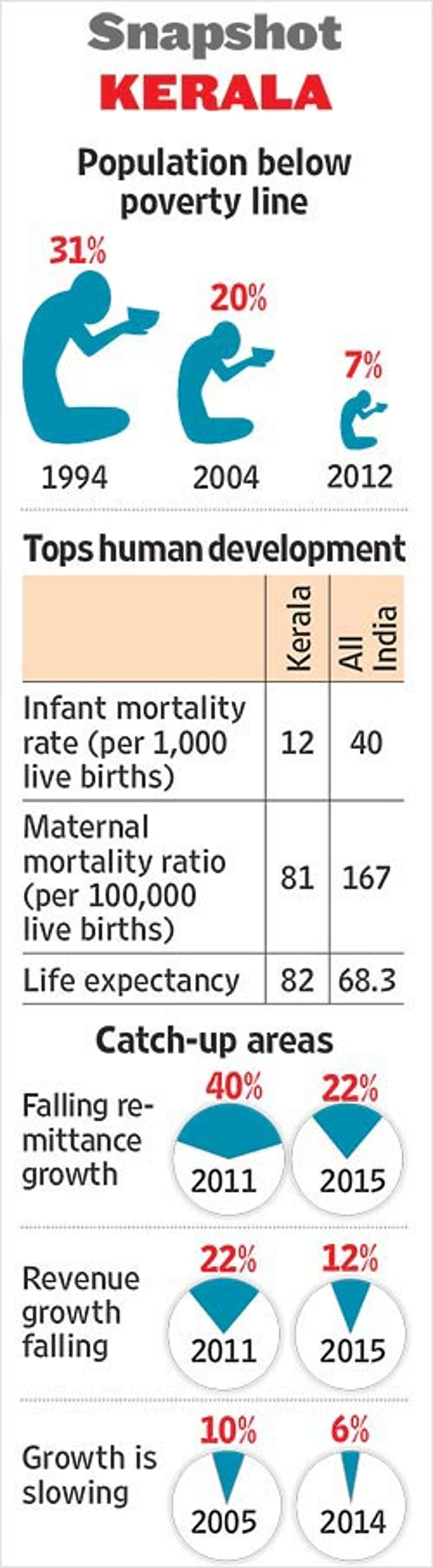

In both Kerala and Tamil Nadu, the OBC legatees of the Renaissance movements, now preoccupied with power politics and the fight for spoils, have forgotten the goal of social equity. Fortunately, some of the gains of the movements remain. Thus Kerala tops India’s human development index table and Tamil Nadu is striving to catch up in social development. The plight of women, Dalits and Adivasis in the two states, though, testify to the collapse of the ideals that animated the early reformers. While Dalits have seen great progress on the education front, empowerment is elusive. Untouchability is still a live issue in many Tamil Nadu villages, and relapse into this evil has been reported from some areas in Kerala too. It was the impact of the OBC movements that held Hindutva forces at bay in the two states during the past 65 years. With their weakening under self-serving leaders, the BJP is making a strong bid to register its presence.

(The writer is a senior political commentator.)

.jpg?w=200&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)