“It was a memorable day for me, being able to honour my roots and the hard work of my migrant parents, and to support the incredible work by Save the Loom,” wrote lawyer Amanda on her recent Instagram post. The accompanying photograph shows her standing before the Supreme Court of New South Wales in a grey sari with a black flare and white stripes under a black jacket. The next image in the post is a handwritten letter from Save the Loom (STL), a Kerala-based social impact agency whose sari Amanda was wearing. It is called the Usha sari from STL’s Vidhi (Sanskrit for law) range of 15 handloom saris for women lawyers. In the letter, STL said it views the saris as a medium to build “better workspaces and pay the right wages”. To the left side of the letter is a tiny label (that is stiched to the sari hem) and reveals the name of its weaver; in this case, Preethy R.K.

That Insta post was possible because three women came together. Amanda, on a career-high, bought the sari. The late Justice K.K. Usha, who inspired the sari’s name, is the first Malayali Chief Justice of the Kerala high court, a champion of women’s issues and fought against discriminatory practices. Preethy R.K., one of Kerala’s many faceless weavers, toiled for 16 hours (two-day shift) on the loom to weave the sari. Law and weaving were once fiercely male-dominated professions, but recent figures show a remarkable turnaround. According to a report by the law ministry in July 2022, women now constitute 15.3 per cent of the law workforce; a long way from when the legal profession was opened to women in India in 1923. And about 92-96 per cent of weavers in Kerala’s Ernakulam district are women after the men left the trade for jobs providing higher pay and better incentives.

The beginning

STL (www.savetheloom.org) founded by Ramesh Menon was the first rebuilding initiative (before others like Care 4 Chendamangalam and Samrakshanam-Reloom) in the aftermath of the 2018 Kerala floods that ravaged the homes, and along with it, 273 looms, in Chendamangalam, the handloom cluster producing GI-certified cotton dhotis (kavi mundus) and saris. It managed to crowd source Rs 4 crore to revive seven handloom cooperatives and the Gandhi Smarak Grama Seva Kendram khadi centres in the state.

But the milestone hardly felt momentous as the handloom industry in Kerala constitutes an ageing workforce—85 per cent of weavers are over 45 years old—earning a minimum daily wage Rs 150, as stipulated by the government then. Weavers would rely on traditional festivals like Durga Puja, Diwali, Onam, Vishu, and Baisakhi, occasions when handloom sales skyrocket from the high demand for traditional wear. But the 2018-19 Kerala floods, followed by the 2020-21 pandemic, put a pause on celebrations. There was a desperate need then to create new inroads into the marketplace, attract young buyers, and ensure better pay for weavers. And a collection of women lawyers opened that door.

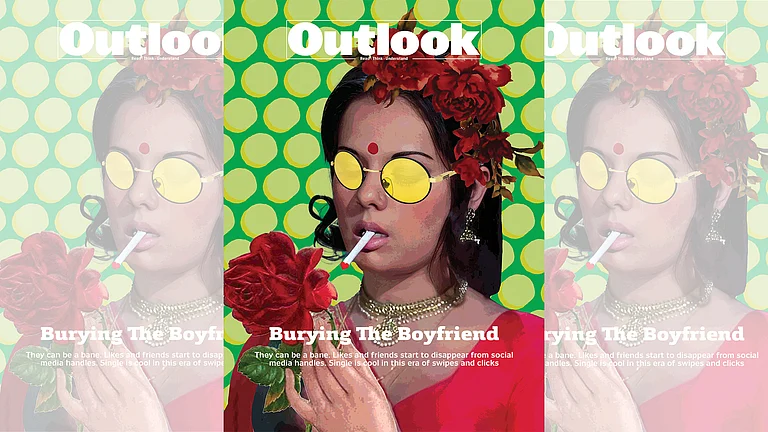

Contemporising a dress code set in stone

Part VI, Chapter IV of The Bar Council of India (BCI) has specific rules relating to the “Form of Dresses or Robes to be Worn by Advocates” in black, white, and grey hues. Women can wear a full-sleeve jacket/blouse, stiff or soft collar, and gowns; or an open-breasted coat with a collar/collarless blouse; saris/ long skirts even in “mellow or subdued colour”; or Punjabi churidar-kurta/salwar-kurta. The Vidhi collection adheres to this BCI-approved dress protocol but even ensures what the young law graduate, intern and lawyer, wants. The generation settles for Punjabi suits or classic shirts and trousers. The additional layers of black jacket and coat, they find, restrict movement and are stifling during summers in courtrooms with poor ventilation, and unfashionable for an evening soiree right after the day’s courtroom session. Following the dress code is sacrosanct, going by the retirement speeches of senior judges like Indu Malhotra, and the numerous occasions when the judiciary admonished lawyers and litigants for dressing casually. Menon was mighty pleased when the R&D dug up serendipitous finds such as the first Supreme Court woman judge, Justice Fathima Beevi, and the first woman lawyer, Anand Chandy, both of whom hailed from Kerala, STL’s headquarters. It felt befitting to launch Vidhi on Justice Chandy’s birth anniversary in 2021.

Nine women weavers weave the Vidhi range of designs named after stellar women judges, namely Cornelia Sorabjee, the first female advocate in India; Justice Leila Seth, the first Chief Justice of the Himachal Pradesh high court; Justice Sujata V. Manohar, who crossed many hurdles;; and the late justices Usha, Beevi and Chandy. These women lawyers of yore were all connoisseurs of handloom saris, had a personal launderer to ensure the saris were crisply draped, played with a wider palette and bold motifs like jacquard; to stand up to stand out, often as the only woman in a courtroom. Comparatively, Vidhi saris blend with the crowd. “The woman of today is no longer fighting for space, rather establishing equal ground, comfort and style,” explains Menon.

Vidhi’s black, white and grey saris, made from pure cotton, use a superior thread count of 2x120 than the usual 80 by 80, and combed yarn to reduce wrinkles. The saris, claim STL, can be washed with other garments as the dye does not bleed. With 60 minutes of drying time, the saris can be worn every day and do not require heavy ironing. They are pre-washed and de-starched by the washermen at the colonial era Dhobi Khana in Fort Kochi.

Justice Usha’s family is STL’s longstanding patron, participating in Menon’s 2018 fundraising campaign. He recalls retired Justice K. Sukumaran, one-half of India’s first judge couple, who visited a weaver’s collective in Chendamangalam with his daughter and Advocate Karthika wrote three cheques: Rs 30,000 to fix the loom of a weaver he used to patronise; Rs 50,000 in his wife’s name for a deserving woman weaver; and Rs 50,000 as an advance payment for his handloom purchases that year. In 2020, in her memory, STL instituted a scholarship titled Usha (University Scholarship for Handloom Artisans) for handloom artisans and their children. Talks are on to facilitate student exchange programmes with the likes of the National Institute of Design and universities abroad. In fact, the specially-abled people from NGO Sree Narayana Sevika Samajam, run by Justice Usha’s daughter, hand-hem the saris for STL.

The plight of women weavers

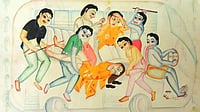

In her 2014 Marg publication, Sacred Textiles of India, which documents the role of handwoven and hand-printed fabric traditions in religious rituals, crafts exponent Jasleen Dhamija links the activity of weaving to prana (Sanskrit for a breath of life) that “uses the human body as a yantra, a meditative powerhouse. This diurnal (daytime) activity is akin to Dhyana Yoga, where the body is disciplined to follow the repetitive movements of the loom—repetition being the core element of any meditative practice. Dhamija compares the union of the warp and weft to the union of man and woman. “The stretched, taut warp that is the base of the fabric is a symbol of the male potency, while the pliable weft that unites, represents female fecundity.” The women have it tougher, she implies, by comparing the creation of the woven handiwork by women weavers to the tedious process of giving birth, as certain looms exert continuous pressure on the loins and the small of the back.

Eight hours of moving to the whims of the loom is just one part of her day. There are household chores and tending after the children and husband. Every weaver, adds Menon, is battling health issues like cancer, arthritis, eye/back problems, and most often, an alcoholic husband. There is no incentive for sick leave or vacation, and the day she’s absent sees a loss of daily wage. At work, she must watch the threads with a hawk’s eye. The threads are brittle, and can break, and unless the broken yarn is seamlessly fixed, the work becomes defective. She has no technical assistance to keep count. For instance, for every 10th count, she must remember to change the shuttle to a new yarn colour if the design demands it. Black yarn can prove nightmarish; the eye gets strained to try to locate defects/errors, which slows down the speed of weaving. When the starched yarn is beaten, a kind of dust mite is released, and to avoid inhaling it, no fan/air conditioner can be installed.

Weaving cooperatives lack capital money and are forever in debt due to the government’s rebate scheme, intended to help faster sales of unsold stocks. If a Rs 1,000 sari is sold at Rs 800, the government is supposed to reimburse the Rs 200 to the societies. “But it can take 3-4 years for the money to reach the weavers,” Menon reveals. For these reasons, existing weavers have barred their progeny from taking to the loom. Their life’s achievements and certificates are because of the loom, yet the loom is why they live in abject poverty. Even their children look down on them. On the 8-9th day of documenting the 2018 floods, when other weavers were frantically looking for parts of their looms that were scattered about their houses by the raging waters, he found one lady happily weaving. Her loom was intact because her husband, before rushing to the relief camp on seeing the flood waters rise, had the presence of mind to dismantle it and secure it to the ceiling. Menon wrote an article about the couple that appeared on Page 1 of a leading daily. But the daughters were angry. “They were embarrassed that everyone now knew that their mother is a weaver.”

Need of the hour

Sceptics point out that the young are not wearing handlooms, and the young are not weaving handlooms. The solution, says Menon, is to create “an aspirational value” in both the maker and the buyer. It is why the Vidhi saris are named after exemplary women in law. With green architect Vinu Daniel, Menon is working to build a publicly funded ‘living museum’, functioning like a studio setup that is well-ventilated space and equipped with good facilities, such that tourists can visit and watch the weavers at work. To see how a thread takes 28 days to become a fabric, how women weavers toil on the loom with only a few breaks and comprehend why handloom fabrics are priced higher than power loom. The circular economy can instil pride in the profession.

The Kerala government engages weavers at a slightly higher minimum daily wages to weave school uniforms. The repetitive exercise of weaving without experiments in dye or design can feel mechanical. Moreover, the uniforms are distributed free of cost. “On growing up, accustomed to the free uniform, this child will never find the handloom aspirational or of value,” says Menon. A small fee can make a difference if directed towards weaving collectives and weaver’s remuneration packages the year round.

STL only produces unstitched yardage and doesn’t venture into design experiments like pre-draped saris, unless a collaborative effort like their ‘Colours of Resilience’ show at the 2018 Kochi Muzuris Biennale, where 20 designers created garments from 15 metres of yardage provided to each one. Instead, the focus lies in improving day-to-day operations. For instance, every handwoven product from a cooperative has the weaver’s registered society number attached. If the fabric is found with defect and returned, the weaver is identified and subjected to a pay cut. “Instead of only punishing them, why not reward them for all those unreturned, well-made saris?” notes Menon.

Meanwhile, the Vidhi saris have found ardent admirers, particularly among senior SC lawyers and judiciary in Calcutta, Bengaluru, besides Kochi. Above all, STL has found a new market. Convocation ceremonies. “A number of law students contacted us before the ceremony, so much so that we were not prepared,” says Menon, who will rectify that next time around.