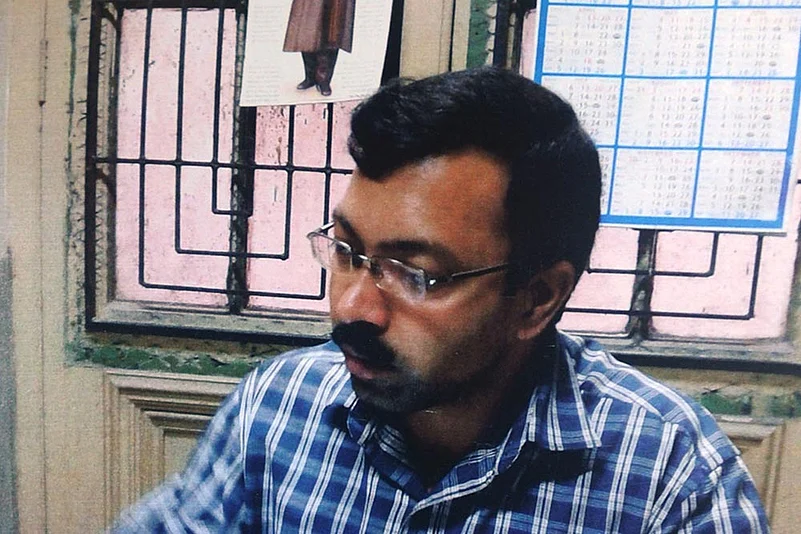

“We are afraid that the case will fizzle out, as most do when the media stops talking about it, and my little brother will never be found,” Anil Upadhyay tells Outlook on the phone from Jaunpur city, UP, where he works as a railway station master. The eldest brother of Sunil Upadhyay, the 35-year-old scientist and chief conservation officer at the Indian Museum in Calcutta (IMK), who is missing since July 2014, says the family has moved the courts in Calcutta for a CBI inquiry. “We do not want to suggest that the CID is not trying,” he says, clearly not wanting to rub the Bengal Police’s detective department, which is handling the case, the wrong way. “But since the CBI is the country’s biggest investigating body, we would feel reassured if it took up the case.”

He wonders why the different agencies cannot work together to trace Sunil. “We are very small people” he says, his voice quivering, “but Sunil was a big scientist. He was a bright student and fought diverse odds, like backwardness, to reach where he did, completing his PhD in Chemistry from Delhi University and being sent to the US for higher studies. Doesn’t the government care about him anymore?” The glimmer of hope when Outlook first spoke to him soon after Sunil disappeared (see Museum of Little Secrets, Aug 4, 2014), has given way to a sense of resignation. “Sometimes my mother searches through the newspapers’ ‘missing persons’ columns and cries. When there is news of a missing person who has been discovered dead, she goes stone cold. We often fear the worst....” he breaks down.

Early last year, the CID had submitted a “final report” to the court of judicial magistrate in Alipore, Calcutta, in which it stated that the investigation drew a blank. The court was not satisfied and directed the CID to continue the probe. CID deputy superintendent Madhushudhan Nath, who is currently in-charge of the case, tells Outlook, “We are leaving no stone unturned. We are following every lead, making inquiries and going through documents. We are even revisiting the leads followed earlier.”

Sources in the CID tell Outlook that their initial view as expressed in the final report suggested the possibility that the scientist may have left on his own. One official justifies this argument with claims such as “he is supposed to have been suffering from depression because of a host of reasons, including work pressure and office politics and was taking medication for it.” Another says, “He didn’t even take his cell phone with him. He could have been in a mental state where he did not want to be contacted.” The scientist is said to have been blamed for the damage to a priceless sculpture, the Rampurva Lion Capital, during the museum’s renovation. Another CID official tells Outlook, “While it is difficult to speculate, the investigation has not ruled out the possibility that the scientist may have met with an accident and lost his memory. We deal with many such cases. It is not unusual.”

But Sunil Upadhyay’s colleagues at IMK, who suspect foul play, are reluctant to accept these explanations. “Sunil was a whistleblower who fearlessly raised questions about corruption in the IMK,” an IMK employee tells Outlook. “IMK is an institute which deals in crores of rupees worth of art and artefacts. From rare gems to antique coins, from priceless paintings to ageless sculptures, the museum is a treasure trove of high-value items. He was convinced that a money-laundering racket was operating with help from within IMK, which formed a chain, involving influential people, including politicians, police and possibly the international art and antique-smuggling mafia.”

Sunil’s cousin, Sirish Upadhyay, tells Outlook, “Just a few days before he disappeared, Sunil had told us that he had been offered Rs 90 lakh as bribe by unknown IMK officials so that he would keep his mouth shut about the smuggling out of some antiques. But he refused. Anyone offering that kind of money cannot be a petty thief. It would have to be someone capable of foul play like kidnapping and eliminating someone.” Not willing to accept other explanations behind Sunil’s disappearance, he says, “If he had gone off on his own, he would have at least withdrawn money for basic survival. But police found no transactions since his disappearance. He only had Rs 50,000—showing how an officer of his stature, who could have minted money, was honest to the core.”

According to insiders, Sunil, who was suffering from depression and possible heart disease when he disappeared—was a rare voice of dissent within the IMK, where corrupt officials allegedly accepted bribes from art and antique smugglers for looking the other way. One such serious charge against these operatives within, according to IMK officials who spoke to Outlook, is that they help in producing duplicates of original artefacts and even in smuggling the originals out, to be later replaced by the replicas. “In one case, a dozen Burmese teakwood beams were burgled out and sold to furniture manufacturers,” an IMK official reveals. The institute was embroiled in a scam in 2011, when a few (among several) Rabindranath Tagore paintings from the museum, which were put on display at the Government College of Arts and Craft, were found to be fakes. “The perpetrators had hoped that the fakes, once passed off as the real thing, would fetch attractive dividends if they could be sold,” the IMK official points out. In another instance, before a visit by then PM Manmohan Singh for the bicentenary celebrations of IMK in 2014, antique coins were hurriedly put on display using common glue (Dendrite, to be precise), instead of a special chemical that is non-corrosive. “The pieces were ruined forever,” the official says. “But behind this was more than mere neglect. It was an attempt to have the coins brought out for repairs and deliberately misplaced.”

Aletter written by Saumyo Mukherji, an outgoing legal consultant of IMK—who infers that his contract was not renewed due to his pursuance of cases of mismanagement and corruption as well as the resultant disagreements with higher ups—addressed to the governor of West Bengal, who is also chairman of the board of trustees of the IMK, enumerates a host of such alleged irregularities, including misappropriation of funds, disproportionate expenditure and underutilisation of allocated money, and even mishandling of and damage to invaluable and rare works of art, sculpture and other memorabilia. The letter raises questions about a sum of nearly Rs 100 crore allocated to the museum for renovation work, which “remains unaccounted for”. Furthermore, to bring the governor’s notice to slackness concerning the safekeeping of the precious collections at the museum, Mukherji writes, “It is generally known that only five to six per cent of the total number of art objects in a museum are put on display.... The rest are kept in separate reserves and exhibitions take place on rotation basis. IMK’s collections exceed one hundred thousand items. Obviously, a large number of objects at any given time are stored in reserves. These reserves are not just in a ramshackle condition, simple security mechanisms such as CCTV cameras have also not been installed, making these vulnerable to theft and burglary.” He points out that this is all the more shocking considering that break-INS, thefts and burglaries have already taken place on more than one occasion.

Another IMC official goes to the extent of suggesting that this is not mere negligence, but a deliberate ploy to keep the option of siphoning off of valuable materials open. “In the past items have been stolen and there was no record of who entered and went out of the vaults. That there were no CCTV cameras to guard the safes was one of Sunil’s biggest complaints,” says the officer. “But for some reason, the authorities seem reluctant to take this most basic security measure.”

In an interview to Outlook (see box), Dr Jayanta Sengupta, who has been given additional charge of the museum since 2015, replies to the allegations against the institute he heads, though IMK workers who make the charges are quick to point out that the soft-spoken professor and scholar, also director of the iconic Victoria Memorial Hall, is himself not culpable. “He is a gentleman who is trying to revive the cultural tradition of IMK, but the museum is crumbling from within because of corruption at various levels; criminal gangs are controlling money laundering rackets inside,” an IMK official says. “We believe our colleague Sunil Upadhyay was silenced because he knew too much and because he raised his voice. And those who removed him are still lurking in these corridors.”