At the beginning of June, when a teacher at a government-sponsored school in Parokata gram panchayat of Alipurduar district in northern West Bengal applied for a loan from Uttarbanga Kshetriya Gramin Bank, a regional rural bank sponsored by Central Bank of India, he was asked to produce a unique document—a certificate of passing the state’s Teacher Eligibility Test (TET). The branch manager later told the media that they were taking no risks while disbursing loans to teachers in government -aided and -sponsored schools, and were therefore asking for the TET result.

In mid-June, a woman in Cooch Behar district’s Nishiganj area sat on dharna in front of the house of a college lecturer. She alleged that she was having a romantic affair with the lecturer but he stopped taking her calls since she lost her school teaching job following a high court order.

By the end of the month, the matrimonial columns in a Bengali daily featured an advertisement saying that parents of a woman in Uttar Dinajpur district were looking for a ‘suitable groom’—that excluded school teachers.

For ages, school teachers have remained a favourite as prospective grooms or brides in Bengali middle class society. But a chain of events that unfolded since the end of last year has so far resulted in the Calcutta high court terminating the services of over 1,200 employees in state government -aided and -sponsored schools, terming their appointments as fraudulent and illegal.

This included 271 assistant teachers for classes IX and X, 609 Group D employees and 381 clerical (Group C) posts. All these recruitments happened through the School Service Commission (SSC) between 2017 and 2019. The court has ordered stopping their salaries immediately, leaving open the scope for asking for a refund of every rupee they have received as salaries. The CBI is also free to ask them how they got their jobs, the court said. Several of these teachers hadn’t qualified in the TET at all.

One of the school teachers who faced termination of job is Ankita Adhikary, daughter of current minister of state for education, Paresh Adhikary. A Left Front leader and minister during the last Left Front government in the state (2006-2011), Adhikary switched over to Trinamool Congress (TMC) in 2019, following which his daughter’s name jumped ranks in the waiting list. The court, in May, ordered Ankita to return all money received as salary within two months, while Paresh is facing a CBI probe.

In this backdrop, last week’s arrest of TMC heavyweight Partha Chatterjee, who was the education minister when the school recruitment scam took place, has left Mamata Banerjee’s party on a sticky wicket. It’s not the first time a major scam has hit the TMC. Neither is the sight of the TMC chief defending her party leaders arrested by central government agencies on charges of corruption a rare one. She roared and thundered, blaming political use of central agencies in all such cases.

Many still remember how, in November 2014, Banerjee led a rally in Calcutta after the CBI arrested TMC Rajya Sabha MP Srinjoy Bose in connection with the Rs 2,500 crore Saradha chit fund scam, and sent summons to several other party leaders, including ministers Madan Mitra and Shyamapada Mukherjeee. In the rally, TMC supporters were seen sporting aprons or carrying placards with “We are all thieves” written on them. In February 2019, she sat on a 70-hour dharna at Esplanade in the heart of Calcutta, to protest an attempted raid by the CBI at the residence of then Kolkata Police Commissioner, Rajeev Kumar, in connection with the same scam.

Even last year, soon after returning to power, she rushed to the CBI’s office at the Central Government Office (CGO) complex in Salt Lake, after the agency arrested ministers Firhad Hakim and Subrata Mukherjee, MLA Madan Mitra and former minister Sovan Chatterjee in the five-year-old Narada cash-for-favour sting operation case. She demanded before the CBI officers that she too would have to be arrested.

The party had a point. The agency hadn’t arrested Suvendu Adhikary, another accused in the same scam, after he had joined the BJP and become the leader of the Opposition in the state assembly. She left after a few hours, though.

But things were different this time. The moment the news broke on July 22 that the Enforcement Directorate (ED) had recovered Rs 20 crore in cash from the residence of Chatterjee’s ‘close associate’ Arpita Mukherjee—the raid at Chatterjee’s residence was going on simultaneously—TMC spokesperson Kunal Ghosh tweeted that the party had nothing to do either with Mukherjee or the cash.

As it appears from Chatterjee’s arrest memo, ED officials, after arresting him at 1.35 am on July 23, asked Chatterjee if there was anyone he wanted to contact. Chatterjee had named the chief minister. The ED officials allowed him to call her four times—from 2 am to 9.30 am—but she did not take any of the calls. While being taken to a hospital for a mandatory health check-up upon arrest, Chatterjee told the media he had tried to contact the party chief but failed.

Gradually, news emerged that the ED found several property deeds in the name of Mukherjee, who did some modelling and acting in the past, in Chatterjee’s possession. In the evening, ministers Firhad Hakim, Arup Biswas, Chandrima Bhattacharya and spokesperson Kunal Ghosh told the media that the party had ‘full faith’ in the judicial system and would take action against Chatterjee if the court found him guilty. There was no word of support for Chatterjee, no suggestion that he might be a victim of political vendetta.

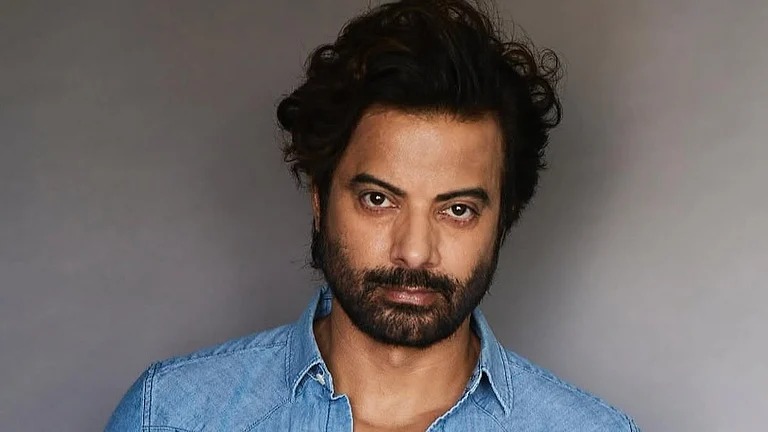

Chatterjee is not any other TMC leader. The 70-year-old, a five-time MLA, is the party’s secretary-general and one of its main spokespersons. He also heads the TMC’s disciplinary committee and serves as editor of the party’s mouthpiece Jago Bangla. After being leader of the Opposition during 2006-2011, he served in different ministerial roles since the TMC came to power in 2011—first as commerce and industries minister, then as education minister from 2016, and finally returning to his old portfolio of commerce and industries in 2021. All the while, he maintained the crucial portfolio of parliamentary affairs minister. He is still the deputy leader of the state assembly.

But the gravity of the scam and the circumstances of Chatterjee’s arrest have pushed the TMC on the backfoot. Justice Abhijit Gangopadhyay’s single bench at Calcutta high court first pointed out a potentially large scam while hearing a series of petitions alleging irregularities in the recruitment for posts of assistant teachers, Group C and Group D employees, and ordered a series of eight CBI probes. All these orders were stayed by a division bench, which replaced the CBI investigation with a probe by a committee led by a retired judge of the high court.

After the committee’s investigations not only corroborated Justice Gangopadhyay’s findings, but also came up with additional details, the division bench gave its go-ahead to the CBI probe and gave the single bench a free hand to direct the investigation the way it deemed fit. The single bench subsequently asked the ED to help the CBI in unearthing the money trail. Chatterjee had to face CBI grilling multiple times following directions by the court.

His arrest gave the TMC’s principal critics—the CPI(M) and the BJP—two days to brand it as an “utmost corrupt party”, and demand the CM’s resignation, taking responsibility for such a massive scam involving a top personality in the party and government. It has been common knowledge that Chatterjee was one of the prime links between the party and the government.

The chief minister broke her silence on July 25, but mostly to defend herself. She cited how she provides voluntary service by not taking any salary, and earns from the royalties of about 120 books she has authored, and from songs she has written and set to tune.

“The CPI(M) and BJP are mudslinging my name and I will never accept it,” she said, adding, “Please do not play with fire. If anyone has done wrong, prosecute him. But do not touch me. I know how to fight back, for I have done nothing wrong.” She also said she was unhappy with some “recent developments” and hinted that Chatterjee may have made “a mistake.”

“In politics, people do make mistakes, but it is important to rectify those. As Swami Vivekananda once said, ‘We have the right to make blunders.’ If anyone makes a mistake, it is better to apologise and rectify it,” she said, adding that she wanted a “time-bound probe” by a fast-track court. “Take three months, but get to the bottom of the SSC scam,” she said, while criticising the “media trial”.

It was possibly not the appropriate occasion—the ceremony to confer Banga Bhushan, the state’s highest honour—for her to make such statements. Realising it, she explained, “If I had not said anything, the people and the media would have said I’m scared, and hence I’ve become silent. But as you can see, that’s not the case.”

A seasoned streetfighter, the TMC chief has always sported a brave face every time a disaster hit her party since its birth in 1998. How and whether she manages to take her party out of the mess of the school recruitment scam will be one of the keenly observed developments in the state in the coming days. After all, she has formally acknowledged that there is a scam, even if she tried to downplay its magnitude.

The CPI(M)’s Rajya Sabha MP Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharya, who has been the main lawyer fighting for aggrieved job aspirants in the SSC scam case, predicts the TMC will find itself further entangled in the scam as the investigation progresses, as he expects the search for the money trail would lead central agencies to the door of more prominent leaders of the party. “Top to bottom of the party and government are involved in it,” he alleged.

As of end-July, public sentiment was hardly in favour of the TMC. “It has become a social problem. I got my job in 2019 and got married last year. After this scam broke out, my wife asked me in passing if I had all my qualification documents right. Every teacher who got a job between 2018-2019 is now being looked at as a potential fraud,” a school teacher from Uttarpara town in Hooghly district said, unwilling to be identified.

(This appeared in the print edition as "School for Scandal")

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya in Kolkata