Any psychiatrist would tell you that extrovertism is nine times out of ten a losing proposition. And the Bible clearly says, ‘blessed are the meek for they, (and not the bold), shall inherit the earth’.

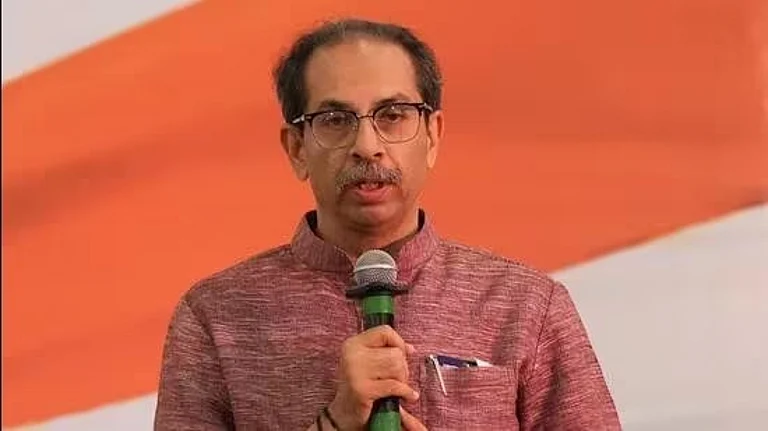

Those two maxims suit the Thackeray cousins, Uddhav and Raj to the T. BJP leaders had always dismissed Uddhav for his humility and modesty as unsuited to politics. They believed Raj to be more of a chip off the old block (Bal Thackeray, the Shiv Sena founder). Yet today, Raj is a spent force while Uddhav is the chief minister of Maharashtra and a very able and successful one at that.

How did this happen? The simple answer to the question is consistency, or the lack of it on the part of Raj, and arrogance, or the lack of it on the part of Uddhav; the pursuit of personal pleasure to the detriment of his politics by Raj, and a clear understanding of the pitfalls in his path by Uddhav that helped him to steadfastly sidestep stumbling blocks and manoeuvre his way to the top.

To begin with, one wonders if Uddhav was at all ambitious about stepping into his father's shoes. It was Raj who believed that the Thackeray legacy was his and his alone, which led him to be rude and arrogant towards Bal Thackeray’s advisors, many of whom were top ministers in the first Shiv Sena-led government in 1995. These so-called 12 apostles—or upnetas—of Bal Thackeray (like Manohar Joshi, Pramod Navalkar and others), then got together to cut Raj’s access to Matoshree by the simple expedient of keeping him continuously on the campaign trail and boosting his ego by saying there was no better speaker than him in the party after his uncle.

Simultaneously, they promoted Uddhav as a go-between and allowed natural ambition to take over and conflict with Raj's interests. Before he knew it, Raj’s supporters were being denied tickets to various elections, he had to wait hours for an audience with his own uncle and his humiliation at the hands of Matoshree’s minions grew too much to bear.

Raj also did not have an original idea to carry forward to the new century, preferring to rely on Balasaheb’s 1960s and 1970s issues of Marathi manoos, migrants, both from south and north, and Muslims. The three Ms have not worked for him the way Uddhav’s inclusivity has worked for the Shiv Sena. Raj continues to define Hindutva in terms of Hanuman chalisas and azaans while Uddhav is now clearly defining his own commitment to Hinduism in terms of what most liberal Hindus believe, and are able to mix their religion with the ideal of Sarva Dharma Sambhav. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Aurangabad last month where Raj did his best to set the two communities on a collision course but no one reacted after an assurance that the chief minister, his cousin, will not allow any untoward incident and would protect the interests of the minorities.

In 2019, it seemed as though Raj had had a change of heart about communal politics, taking on Narendra Modi in no uncertain terms but none of his rhetoric received the desired electoral results. While he got the crowds, they still voted for the Shiv Sena. And while, with his angry demagoguery, Raj is hardly able to win any seats, Uddhav has been doing better than even his own father by netting a substantial number of seats in the assembly. Thackeray never got more than one assembly seat at a time, Uddhav’s scoring rate has been an average of 60 out of 288 seats in the assembly, with or without an alliance with the BJP. It is an indicator that the core Shiv Sena voter is more impressed by calm assurances like that made by Uddhav than the fire and brimstone of Raj which, if it could destroy the peace, would not be in their own economic or social interests.

Their sons, Aaditya Thackeray, who is a minister in his father's government and Amit Thackeray, recently formally launched into politics by father Raj, have made their presence felt but while Aaditya is in his father’s mould, Amit appears more introverted than Raj. While he has been campaigning for the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena, the party’s diminishing electoral returns seem to be keeping him from carving a niche for himself. However, Aaditya’s concerns are younger and go down well with GenNext and if the Shiv Sena's fortunes remain steady he is likely to emerge as one of the pillars of not just the Shiv Sena but also the state’s leadership.

Why Raj needs to redefine his politics in the interest of his son’s future is also because no one does communal politics today better than the BJP. And Uddhav has married the Marathi manoos well to both Hinduism and secularism, so people are unlikely to settle for weak, powerless wannabes in either case. For the moment, though, Uddhav seems here to stay while Raj seems to have no raison d'etre beyond the here and now.

(Sujata Anandan is a Consulting Editor with the National Herald)