Ironic is it not, that a film on the Emergency was held up by what we call the Censor Board (officially the Central Board of Film Certification)? For it was during this infamous Emergency from 1975-77 that the Indian media, at that time essentially the print media, faced direct censorship for the first, and only time, since Independence.

On June 26, 1975, when the Indira Gandhi-led government declared a state of Emergency and announced that there would be press censorship, none of us knew what this meant. Censorship? How? Who would execute the policy? What were we as journalists supposed to do?

At the time, I was working with a small independent news magazine called Himmat Weekly, founded by Rajmohan Gandhi who was also the editor-in-chief. I had joined as an assistant editor, and as the name suggests, our remit was to have the courage to call out the powerful and write about the powerless. Within six months of the declaration of the Emergency, I became the magazine’s editor as R M Lala, one of the founding editors, stepped down.

On that first day, our small team of mostly young journalists had to decide what to do. Should we submit to censorship? Or shut shop? Or should we find a way around it, even if it meant taking considerable risks given that practically all the Opposition leaders had been swept up and thrown in jail and even journalists and other critics were not spared. Perhaps it was our youth, our ignorance or sheer bravado that made most of us feel we should fight censorship and continue to publish as long as we could.

Much like the other, and better-known instances of defiance, such as the The Indian Express printing a blank front page to inform its readers about censorship, Himmat Weekly too ran blank editorials in its first two issues. Only to be told that even leaving a blank space violated the censorship guidelines.

These “guidelines” trickled down to the press during the days we were not informed that we had to clear all our copy with an official. As a result, in those initial weeks, publications took chances to see how far they could stretch the meaning of these guidelines.

The guidelines were vague. The first one, for instance, stated: “Where news is plainly dangerous, newspapers will assist the Chief Press Adviser by suppressing it themselves. Where doubts exist, reference may and should be made to the nearest Press Adviser.” In other words, we were left to decide what was “dangerous”.

But that window closed quite rapidly. The bigger newspapers were sent a representative from the censor’s office who sat in the newsroom in the evening and checked copy. We, who were small, and one had hoped so insignificant, that we could escape the eye of the censor, had to physically go each day with our typed copy to the censor’s office, wait till he decided what could and could not be printed, and scramble back to find enough copy to fill the magazine.

The guidelines were not set in stone. They morphed and changed as new advisories were sent from the centre through the Information and Broadcasting Ministry, then headed by V C Shukla. The nature and volume of these guidelines came to be known only after the Emergency when a commission of inquiry under Justice J C Shah was established. The Shah Commission report revealed that new guidelines were sometimes issued verbally and a phone call from the ministry in Delhi to the censor could lead to action against a publication deemed to be defiant or running material that was “prejudicial”.

For instance, Himmat Weekly was hauled over the coals for printing this quote from Mahatma Gandhi: “The restoration of free speech, free association and free press is almost the whole of Swaraj.” We were informed that this was “prejudicial” and asked to pay a fine of Rs 20,000—a huge amount in those days for a small magazine that could barely break even. Instead of paying it, we went to court. Another story that got us into trouble was for reporting that on October 2, 1976, Acharya Kripalani and others, including Rajmohan Gandhi, had been detained for going to Raj Ghat on Mahatma Gandhi’s birth anniversary.

On that first day, our small team of mostly young journalists had to decide what to do. Should we submit to censorship? Or shut shop? Or should we find a way around it, even if it meant taking considerable risks.

I give these examples to explain the arbitrary nature of censorship and how power is wielded during times when no one can ask questions. The person in-charge of censoring the press in Maharashtra was a senior journalist, a former editor of The Indian Express. Many of us had known him in his earlier avatar. Yet, as fellow journalists, we could not argue with him or demand an explanation for why he decided what was “prejudicial” or violated the ever-expanding list of censorship guidelines. He knew he had the power, and we knew the price of defiance.

Despite this, small journals like Himmat Weekly, Freedom First edited by Minoo Masani, Janata Weekly, whose publisher Dr G G Parikh is now 99 years old and still as feisty as ever, and others found ways to get around censorship by taking calculated risks.

In spite of our limited reach, these journals remained under scrutiny during the entire period. Himmat Weekly was forced to find another printer as the place where we had printed the magazine from its inception was told that it risked being shut down if it continued to print magazines like ours. We survived, just about, by raising money from our readers to buy a small printing press. By shouldering the legal risk of any fallout from the content we carried, we were somehow able to persuade another printer to print the bulk of the magazine.

Censorship worked in other ways too. The government had divided publications into the following categories: positively friendly, hostile, and continuously hostile. This determined who would receive government or public sector advertising. For journals like Himmat Weekly, obviously in the third category, this meant that the few advertisements we did get from some public sector companies and banks stopped. Given our precarious financial situation, which fluctuated each week depending on the advertisements we received, this was a virtual death blow. Yet, the magazine managed to survive for the entire period.

This form of indirect control on the media did not disappear once the Emergency ended in 1977. Even today, governments, at the Centre and particularly in the states, leverage advertising to exert editorial control. The only difference now, as compared to the 1970s, is that the private sector has grown and is a substantial source of revenue for the media. But then that leads to another kind of editorial control evident in the virtual absence of rigorous investigative reporting in Indian media on the many transgressions of big business.

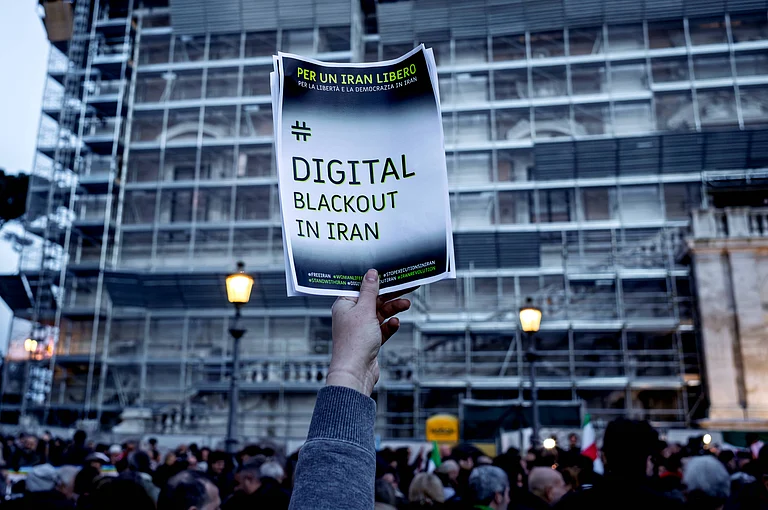

Furthermore, efforts to exert direct control on the media have accelerated in the last decade under the Modi government. The pressure on independent digital news platforms is especially apparent. Even if their reach is much smaller than the bigger media houses, they are under scrutiny, much as small magazines like Himmat Weekly were during the Emergency. Although the current government has backtracked on some of the regulations it had planned to introduce to control independent media, such as provisions in the Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill 2023, the desire to control is evident.

Censorship during the Emergency blocked out the voices of dissidents. But it also silenced the voices of the poor and the powerless. Today, almost five decades later, we must ask ourselves: is the Indian media, bigger and more diverse than during the Emergency, really all that different?

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Kalpana Sharma is an independent journalist and author