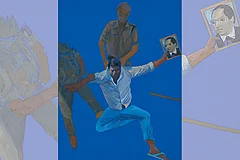

Seventy-seven years ago, our martyrs won freedom from British colonial rule. Three years later, we gave ourselves a Constitution that guaranteed a plethora of freedoms, inspired not by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) but the indigenous ethos of our own freedom movement. Today, having traversed into the Amrit Kaal, these guarantees appear to have expired, needing a new guarantee from our supreme ruler that the Constitution itself will survive. If the likes of Bhagat Singh were to see the state of India’s freedom today, they would certainly ask themselves what was wrong with the British rule that they went to the gallows fighting them.

Bhagat Singh rather had presciently realised the futility of freedom if it just meant transfer of power from British capitalists to Indian capitalists. Precisely the same happened in 1947. The Congress party, which assumed power after the departure of the British, essentially represented the capitalists and landlords. It continued with the colonial state apparatus that had ample scope for liberal vibes in consonance with the new Constitution, which was a rehash of the British Constitution. It could adopt a republican camouflage to manage the Keynesian mixed economic model with heavy state investment in infrastructure that would facilitate capital to prosper. In the process, some benefits trickled down to the common people. Over the next 40 years, it faced several crises, which it responded to with an increased authoritarianism culminating in the declaration of Emergency in 1975 and thereafter a switch to a neoliberal economic model, representing the rise of conservative and anti-socialist forces. It came handy for the right wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP,) which was hitherto a marginal force, to come out with its communal gimmicks and grab political power in 1998 by coalition and on its own in 2014.

Peoples’ freedoms underwent systematic erosion during the Congress rule over five decades. It creates an illusion therefore that the blatant decimation of peoples’ rights under the BJP rule today is not a new phenomenon. It needs to be understood that the BJP is a political offshoot of the ideological fountainhead in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), whose goal is to re-establish the Hindu Rashtra, patterned on a weird mix of Brahminism and 19th century fascism. This corporatist creed does not recognise peoples’ freedoms. It imposes duties on them towards the state which behaves like a fiefdom. The apparent quantitative increase in violations of peoples’ freedom needs to be seen as qualitatively different from what has happened so far.

Isaiah Berlin’s distinction between negative and positive liberty provides a nuanced understanding: negative liberty is freedom from interference, while positive liberty is the capacity to act upon one’s free will. Both forms, however, are fraught with complications.

Freedom, a concept deeply embedded in the human psyche, has been a clarion call for revolutions, the foundation of democracies, and the aspiration of individuals across the globe. It is celebrated as an inherent human right and a cornerstone of modern civilisation. However, the reality of freedom is often more complex and elusive, resembling a mirage that recedes as one approaches it. Freedom, in its purest form, is the absence of external constraints on an individual’s actions. Philosophers John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau posited that individuals possess natural rights to liberty, the protection of which is the reason governments exist. However, this idealised vision of freedom is inherently limited by human society.

This all translates into people having certain basic freedoms to live as human beings, and which further extends to having other civil rights so that they realise their human potential in a social setting and also contribute to the development of the latter. All these freedoms have been well enshrined in our Constitution. But what is the reality on the ground? The very basic freedoms that enable people to live as humans, such as freedom from hunger, freedom from disease, freedom from livelihood uncertainties (lack of means of production and employment) and freedom from injustice appear to be meaningless rhetoric for a vast majority of our people.

There are nearly 195 million undernourished people in India, and 43 per cent of children are chronically undernourished.

Last year, the Global Hunger Index ranked India 111th out of 125 countries with a score of 28.7. India ranked lower than all South Asian countries except Afghanistan. Even our bête noire Pakistan got the 102nd rank and a score of 26.6. Our neighbouring countries Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka were also better ranked at 81, 69 and 60, respectively. According to the UN, there are 195 million undernourished people in India, a quarter of the world’s undernourished population. In addition, 43 per cent of Indian children are chronically undernourished. The very fact that the government had to resort to provision of free food grains to 81.35 crore beneficiaries for the next five years bespeaks of the reality of freedom from hunger. It costs peanuts to the government to feed people like pigs in pigsties so that they do not create a nuisance in its process of transferring the country’s wealth to its cronies.

As for freedom from disease, suffice to say that India’s healthcare system is the world’s most privatised. A 2019 survey found that over 37 per cent of Indians reported at least one health condition. In 2017–2018, 41.73 per cent of adults and the elderly in India reported at least one chronic disease. The most common chronic diseases were hypertension, diabetes and arthritis. In 2019, 17 per cent of Indians reported anxiety and 10 per cent reported depression. Despite bombastic slogans like Swachh Bharat, poor sanitation, hygiene, and lack of clean drinking water make India vulnerable to communicable diseases, with 1.2 billion people at risk. Diarrheal diseases, lower respiratory infections, iron-deficiency anaemia, neonatal disorders, and tuberculosis are still major public health problems in many poorer northern states. The Ayushman Bharat scheme of the government to provide health coverage to underprivileged citizens disproportionately benefits insurance companies and further impoverishes people.

A 2014 report by UNESCO, says India has 287 million illiterate adults, 37 per cent of the world’s total. However, some estimates suggest that over half of the population lacks basic literacy skills. The overall situation of our educated people is no better. Their numbers are swelling because of the whims of the unscrupulous rulers to create optics for burgeoning youth, but they’re often dismissed as unemployable. The so-called demographic dividend is turning into a veritable disaster, endangering the future of the country.

These are data bits in evidence for the pathetic state of our basic freedoms. The injustice people are made to endure is homomorphous with their lives. Beyond these basic freedoms, there are many freedoms couched as fundamental rights. They are equally crucial for our healthy civic life. Entire part III of the Constitution enumerates these rights: Right to Equality, Right to Freedom, Right against Exploitation, Cultural and Educational Rights, and Right to Constitutional Remedies, which is to move the Supreme Court for the enforcement of any of the fundamental rights.

However, these freedoms are not absolute, and truncated with 'reasonable restrictions' that the State can impose in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, State security, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency, or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation, or incitement to an offence. This constitutional space has been exploited by successive governments to deny all freedoms to the people. It has created holy cows of national security, and public law and order, which led to inventions of several labels like terrorist, Jihadi, and Maoist, which in turn led to creating an arsenal of draconian laws and surveillance infrastructure. It serves the government to eliminate any impediment in their path to achieve the Hindu Rashtra, which Ambedkar had presciently called “the greatest calamity for this country” that “must be prevented at any cost.”

Unfortunately, it has exposed the limitations of his Constitution in both ways: First, in providing enough checks and balances over unscrupulous governments turning against the people. Its statist core at the cost of people stands totally exposed by the manner in which the institutions collapsed to subserve the partisan interests of people in power. Second, it did not provide any recourse to the people to prevent these overtures, except for approaching the Supreme Court, knowing full well that it would be nothing but a legal fiction. The judiciary, the ultimate constitutional watchdog, has become a tool to put a stamp of approval on every whimsical move of the government against people.

While the people have been losing their freedoms, a minority of wealthy people are enjoying all freedoms: freedom to have policies in their favour, unbridled freedom to exploit and amass wealth, and freedom to display it vulgarly. The inequality that has grown in recent years exceeds that during the British period, and is telling evidence for the pathetic state of freedoms of the common people.

Returning to Bhagat Singh’s dictum, we need to rethink our entire tryst with destiny.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Anand Teltumbde is an Indian scholar, writer, and human rights activist

(This appeared in the print as 'The Death of Freedom')