It is a truism familiar to peacemakers: that the solution to an ethnic conflict is drawn long before the parties are willing to accept it. In Northern Ireland, the solution was sketched 20 years before the Belfast Peace Agreement. In Bosnia, the contours of a solution—one that the international community could force upon the warring parties—were discussed even before the war broke out. In Sudan, the solution was mooted 30 years before the Comprehensive Peace Agreement.

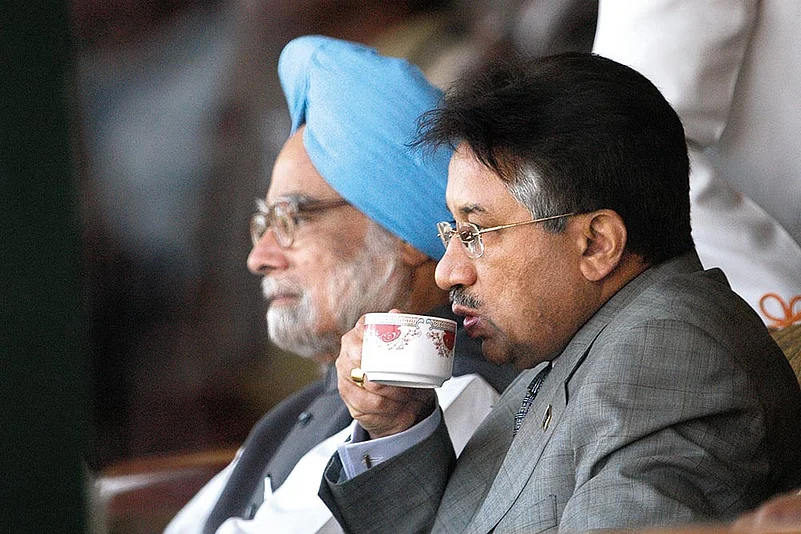

In Kashmir, successive Indian, Pakistani and Kashmiri governments as well as dissidents discussed possible solutions for decades. They came close to a framework agreement in 2004-06, in the backchannel of then Indian PM Manmohan Singh and then Pakistan president Pervez Musharraf. The elements that went into the framework had been on the talks agenda in one form or another for over 20 years. In brief, they comprised autonomy or self-rule for divided Kashmir, freedom of movement and joint economic development, combined with demilitarisation and security guarantees by both India and Pakistan.

The advantage of the framework solution was that it offered something to everyone. The Indian government could claim autonomy had always been the bedrock, the Pakistan government could claim it was accepted as a party in Jammu and Kashmir, and Kashmiri dissidents as well as elected leaders could claim they had reunited divided Kashmir, albeit de facto and not de jure. The roadmap that anchored the talks combined CBMs (confidence-building measures), parallel tracks, a solution partially acceptable to all, and the coming together of several key actors, in an internationally favourable environment (the US, EU, China and Russia all backed it).

Why, then, did the framework talks fall apart when they were so promising? To begin with, the actors were divided. Whether Musharraf was ever serious is in doubt. The Pakistan Army’s corps commanders split down the middle and the country’s political parties were not consulted. Groups such as the Lashkar-e-Toiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed were implacably opposed—indeed, they consistently targeted the peace process with terrorist attacks. In India, the BJP, then in Opposition, was vociferous. An inexperienced media was more often hostile than supportive.

Changing circumstances since then underline how costly the lost opportunity was. Musharraf’s civilian successors tried to restart peace talks with India, but were halted by the Pakistani military. The NATO drawdown in Afghanistan and the Syrian war deflected international attention. The withering of the 2004-07 process left a vacuum that spoilers were able to exploit. New forms of protest broke out, such as pelting stones at the police and security forces. The summer of 2010 saw daily stoning protests in which 120 young men died and several thousand civilians and security forces were injured.

The Manmohan Singh administration, in paralysis for three months while violence escalated, finally rallied to adopt a multipronged ‘hearts and minds’ policy, combining CBMs, security reforms, political dialogue towards a solution, and governance, which gradually yielded results. By late 2011, the state was ripe for a renewed peace process, as the steeply declining figures of attacks and casualties showed.

As one of the Indian government’s Group of Interlocutors, who submitted a report in October 2011, I and my colleagues were deeply disappointed that our report was shelved. Many of the issues we touched upon then lie today at the core of renewed crisis in Jammu and Kashmir—instituting security and human rights reforms, including phasing out the use of pellet guns, taking political dialogue to the next level of policymakers and dissident leaders, addressing youth alienation through diverse economic, social and perspective measures, and healing the rift between Jammu and the Valley.

Though we believed these measures were urgent, we were not able to convince the Manmohan Singh administration. My colleague in the Group of Interlocutors, Dilip Padgaonkar, tried hard to persuade the subsequent Modi administration too, but failed. Looking back, I now wonder whether 2011 was the last chance of peace for a decade or more. Bad as the situation was in 2010, it is infinitely worse now.

Coming in rapid succession, Shujaat Bukhari’s killing, the withdrawal of the Ramzan ceasefire and the BJP’s toppling of the coalition government have plunged Kashmiris into the depths of despair. Commentators warn that fear has gripped the Valley, with a deep and abiding sense that the Indian government and, by extension, the Indian people care little for Kashmiri lives. Many sadly believe the grave situation will persist until the 2019 general elections. That would be a disaster, leading to more deaths, more anger and more alienation. This cycle of violence has to stop.

History shows we can do a great deal to lower the violence, if not completely end it. The Manmohan Singh administration’s ‘hearts and minds’ policy led to a fall in deaths, injuries and human rights violations in 2012. It also showed the policy should have continued even after the track with Pakistan had shut down in 2007. The 2008 Mumbai attacks and the vacuum that followed allowed Pakistani armed groups to resume their spoiler role. Now, with the elections in Pakistan closing in, and so many Pakistani sectarian and radical Islamist groups allowed to contest, spoilers will multiply.

From 2014 on, the peacemaking vacuum has been highlighted by one or another crisis in the Valley and parts of Jammu, culminating in the recent horrors of June. If worse is to be prevented, there are several urgent steps to be taken, such as improved administration, security reforms, human rights protection, interlocutor-based CBMs and reconciliation moves, especially cessation of rhetorical hostility. And then, after six or nine months, fresh elections.

Governor N.N. Vohra is a seasoned Kashmir negotiator and administrator. He has already started stepping up administration and, if he accepts a further extension and is given a free hand, he could restore sufficient confidence on the ground for a peace process to restart by 2019.

Ironically, several of the issues raised in the report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights that so offended our policymakers—it has serious gaps and the occasional inaccuracy, and could not have been worse-timed, but nevertheless makes valid points—were the subject of recommendations in our report too. We had discussed the proposals made for repeal of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) by the Justice Jeevan Reddy committee of 2006 and suggested a new Army Act incorporating the Supreme Court’s guidelines; recommended drastic amendment of the state’s Public Safety Act; asked for amnesty for stone-pelters (except those guilty of causing significant injury); transparency in the Macchil court martial; full implementation of the human rights recommendations of the Prime Minister’s Working Group of 2005-06; and a judicial -nquiry into the unmarked graves.

A few of these recommendations were acted upon by the Manmohan Singh administration. An experts group suggested non-lethal measures to replace the use of pellet guns, and then CM Omar Abdullah announced an amnesty for first-time stone-pelters. But implementation of the latter was weak and, before the former could be implemented, the 2014 general elections brought a BJP-led government to power.

Will any of these measures be taken now? Today, the problem of actors outstrips the problem of circumstances. Over the decades, successive Pakistani governments repudiated the gains made in India-Pakistan peace initiatives, while successive Indian governments did not. Until this time.

(The writer is a political analyst)