Waiting

Are we in a post-ideological age? No, we are submerged in it. The term ‘post-truth’ is merely an example of the impact of ideology on our speech habits. What does it mean? We can approach the meaning of the term ideology by recalling certain historical events; locating the presence of ideology in them; and, in the way they are understood.

But we need to be cautious. The self-images and justifications of rulers across the world are certainly weakening. Their proclamations carry less conviction. We could call this ideological implosion, a phenomenon indicated by names such as the USSR, Brexit, Zionism and MAGA. Establishments are grappling with self-made crises. This does not signify the end of ideology. It shows us that faced with political disintegration, rulers are ramping up hateful and militarist propaganda. Now, ideologies which celebrate violence can unleash a reckless momentum that can be very dangerous. I call this tendency nihilist, because the term has the same root as annihilation.

Turning Points

On June 20, 1791, France’s monarchs attempted to flee from Paris toward the German border. They were recognised and arrested at the village of Varennes, not far from their destination. The crucial factor was the slow movement of their coach, heavy with the Queen’s possessions. Their arrest ended the chances of a limited monarchy and strengthened the proponents of republicanism. It also led eventually to their execution.

On November 7, 1917, the Bolshevik party seized power in Russia in the name of the working class. Soon after, 44 million Russians voted for a Constituent Assembly, a long-awaited milestone for Russian democracy. But the results did not give Lenin’s party a dominant position. When it met on January 5, 1918, the members refused Lenin’s demand that they limit their own power. On January 6, the Assembly was forcibly dissolved, thus ending the possibilities of a moderate turn in Russian history; and igniting a bloody civil war. The whole affair was an ideological contest about the legitimate representation of Russian workers and the Russian people.

October 27, 1962, was the most dangerous day in history. The US Navy had blockaded Cuba during the missile crisis. A Soviet flotilla was on its way, accompanied by a submarine armed with nuclear torpedoes. In the Caribbean, its crew could not communicate with Moscow. When an American destroyer began to drop depth charges on the submarine, its crew armed their torpedoes. But the launch required the consent of all three senior officers aboard. Vasily Arkhipov was alone in refusing permission. The crisis subsided, but not due to high-level statesmanship. Neither Kennedy nor Khruschev saved the world from nuclear war. It was a lone commander in the Soviet Navy.

In December 2000, the US Supreme Court intervened in the presidential election results in Florida, and effectively handed the Presidency to George Bush despite clear indications that Gore could win. The consequences that flowed from this included two Iraq wars, and other ramifications for American democracy. We are left with the question: who elects America’s presidents?

All these events involved decisions with momentous consequences. Yet there are schools of thought which believe in the inevitable motion of history. But nothing is inevitable. There is also a tsunami of opinion which wants to ‘rectify’ history, to purge it of unpleasant memories. These thought patterns, the first academic, the second a product of political dream factories, are instances of ideological thinking. And they are related to the way we understand time.

Endless Deferral

The word ideology was invented by French academicians in the 1790s as part of research into the source of ideas. This usage changed—Napoleon used ideology as a nickname for theories which prevailed amongst ‘hot-brained boys and crazed enthusiasts.’ These days, we use ideology to refer to party programmes. Three themes link us to our subject matter: time, language, and conscience. All of them concern the way we think, speak and act. These issues are complex, but cannot be brushed aside. An excellent introduction to them is George Orwell’s 1984, whose first chapter contains this insight: ‘Who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’ This implies that the control of the present is a means to manipulate public imagination. Nietzsche put it another way. Commenting on his fellow Germans, he said: ‘They belong to the day before yesterday and the day after tomorrow—but they still have no today.’

This sums up the ideological imagination: we have no today. We hate the present; we dream about an imaginary past; and, we yearn for a bright future. The future is the place where the past will be rectified. And thus, we find ourselves in a permanent waiting room. We pass time. Life becomes ‘a joyless quest for joy’.

Doctrines about the bright future can be termed dynamic. There are also status-quoist doctrines, such as market fundamentalism (capitalism as a force of nature); legal ideology (the equation of justice with law); and, eternal dominion, as in Pax Brittanica, or the ‘end of history’. These habits of thought are seriously misleading, but efforts to understand them are few and far between.

Language Games

Ideology is a version of sophistry. Whereas philosophy is the love of wisdom, sophistry is the love of skilful rhetoric. It is not concerned with truth, but contests the very reality of such a concept. Thus, in the first chapter of 1984 we find terms such as newspeak, doublespeak, doublethink, reality control; and the slogans ‘War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength’. All these are examples of the destruction of language.

The term narrative has become fashionable nowadays. There are many words available to refer to events, such as description, version, report, and story. But we rarely use them. Everything is a narrative—a term which carries the flavour of fiction, and has its place. But if there is no difference between events and accounts of those events, then how can we discriminate between competing versions? Don’t they all become true or false as per our convenience? What becomes of justice? Is it just a throw of the dice? Is that what we want it to be? How may we talk about global warming, conflict, or any contentious matter if we flatten all differences with the word narrative?

All ideologies are narratives, so if people change affiliations for clearly selfish reasons, obviously truth means nothing to them. But should it mean nothing to the rest of us? Or have we accepted that the means justify the ends, and that it is fine for some people to indulge in non-stop lying in order to exercise total power over others?

Orwell describes the servants of a totalitarian order denying objective reality while keeping account of the denied reality: “Even in using the word doublethink it is necessary to exercise doublethink. For by using the word one admits that one is tampering with reality; by a fresh act of doublethink one erases this knowledge; and so on indefinitely, with the lie always one leap ahead of the truth.”

Once reality is reduced to fiction we are in a world of total control. This is the goal of tyrants: to replace truth with the ‘spirit’ of nations, classes, communities and castes. Truth will have no autonomy, and conversation will be reduced to shouting. We shall be left with nothing but recipes for endless warfare.

Sovereignty as Eternity

Traditional epics depict the quest for justice; the tragedies of life; and, the assurance of the victory of the good. But goodness cannot be defined by science. There is something metaphysical about goodness, whether or not we believe in God. And because authority needs to present itself as good, there is a connection between theology and power.

But what happens to multi-faith societies? In philosophy, this query is described as the theological-political problem: should we be ruled by divine guidance or by unaided human reason? How may we decide this? If the first, who represents God? If the second, how can we discuss justice unless we are free to think and speak? To insist that the faith of the numerically dominant is the ultimate truth is another way of saying might is right—a recipe for civil war. The decent way is to accept that justice and virtue are prevalent in all cultures; and that a responsible polity will maintain a peaceable dialogue between them. This is what Gandhiji was attempting.

Over the past two centuries, the sovereignty of justice and the good has been perverted into the tyrannical fantasy of eternal power. This humanisation of eternity is an illusion. Some people and parties think they are destined to rule forever, in the name of the Nation, Proletariat, People, etc. But the Creator of the universe is unlikely to be bothered about nations and parties; nation-worship and party-worship are new forms of atheism. They are ideologies.

Where the Mind is Without Fear

For classical philosophers, conscience was the judge within the soul, the spark of the divine. But conscience can be self-destructive, and ideological fixation generates this tendency. In his book Treason of the Intellectuals (1927) Julien Benda wrote: “Our age is the age of the intellectual organization of political hatreds… one of its chief claims to notice in the moral history of humanity.” He was referring to the surrender of moderation to the nationalist cults of the 1920s.

One of the sources of evil is the uncontrolled ego, noted in texts such as the Bhagwad Gita (ahankara), and in Dostoevsky, for whom the will to power was the root of evil. Ideology trivialises good and evil; and undermines our capacity to recognise the difference. An example for us is the moral tension on the question of ahimsa, represented by the figures of Mahatma Gandhi and V D Savarkar.

Ideology silences conversation, and replaces it with sneering. We do not possess it but it possesses us. It destroys our capacity to think; while giving us the illusion of complete knowledge. Keeping a distance from ideology does not imply permanent neutrality; but permanent alertness.

We can rewrite history books, but we cannot rectify history. We cannot un-invent the atom bomb, undo the harm done by the beheading of Loius XVI and his Queen; punish Palestinians for the Holocaust; or indefinitely fight battles with the Mughals. We cannot punish the living for the wrongs done by the dead. We cannot keep dreaming of the ‘final victory’ of our faith or doctrine. Final solutions are never final.

Rabindranath Tagore’s 1910 poem Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo (‘Where the Mind is Without Fear’) is an answer to the propaganda machine. Public opinion will never be devoid of ideology; but we shall destroy ourselves without philosophical courage. There’s a Yiddish proverb which says: The truth never dies, but is made to live as a beggar. Let us sprinkle some water on this wilting plant that refuses to die.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

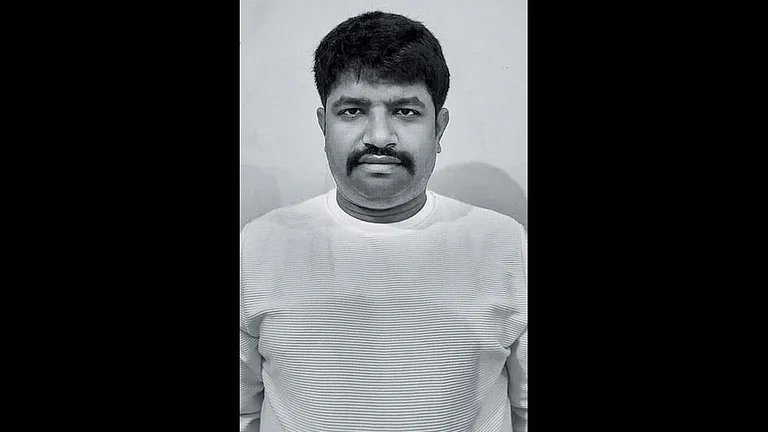

Dilip Simeon is a public intellectual and scholar of the history of labour