“Is Gandhi himself dead?” This was one of the questions in the e-mail Sunil Menon sent, charging me with this piece in a way that I found unavoidable. I write this to reply: yes. But yes in two senses, and the second sense especially brings us to a Gandhi whose spectre is still alive. For death in both senses, moreover, there is a symptom—the word Harijan.

1

The first yes: after a prolonged illness, an entire life lived tenuously, a certain Gandhi, call him the theological Gandhi, died somewhere in the second half of the 20th century. When exactly he died, we do not know. But of his illness and its progress, there is a rough marker—the demise of the word Harijan. If Google ngram is a measure, then ‘Harijan’ hit its peak in 1974, and then began its rapid decline, becoming less common than ‘Dalit’ around 1994.

To understand the work done by the term ‘Harijan,’ we must begin elsewhere—with the term ‘untouchable’. Through most of the 19th century, the most common word to describe the lowest castes was ‘outcaste’. The Oxford English Dictionary notes the first use of ‘untouchable’ in its distinctly Indian sense in 1909. Prior to this, ‘untouchable’ had not acquired its metonymic and systemic sense. For example, S.V. Ketkar’s classic, The History of Caste in India (1909), describes the position of the Mahars as “foul and untouchable”; for him, untouchable is not yet a noun. The word likely spread explosively from around the 1910s, as did ‘untouchability’ as the name for a system of discrimination. And as the historian Ramnarayan Rawat notes in ‘Genealogies of the Dalit Political', it is only about a decade later that the Hindi word acchut comes into play in its contemporary sense.

This is very intriguing. After all, lower castes had for centuries experienced prohibitions on touching. And such prohibitions were only one part of a whole panoply of vicious forms of subordination they suffered. Even in the 19th century, knowledge of the practices of untouchability was commonplace amongst both the British and the English-speaking Indian elite. Why then, suddenly in the early 20th century, did the nouns untouchable and untouchability become the new metonym for the systemic violence that lower castes had encountered for centuries?

I do not have an adequate answer to this question. But it was possibly connected to the anxieties that accompanied the emerging middle-class nationalism. This nationalism drew on a liberal framework—it demanded rights for Indians, and also some degree of autonomy.

The liberal framework could have, first, made ‘touch’ the most prominent aspect of the various vicious practices of caste discrimination. Liberalism is agnostic about touching as public activity, rendering it a matter of individual choice. This individualisation of choice in relation to touch, crucial to the everyday life of liberalism, would have rendered especially visible the proscription on touching. Could this relation have helped create and consolidate a new metonym for the violence of caste discrimination—untouchability?

Second, liberal citizenship emphasises autonomy, an order where individuals treat themselves and others as ends rather than as only means, and create a law-governed community on this basis. Autonomy presumes self-respect: those who do not respect themselves will not be able to demand that they be treated as ends (or, for that matter, treat others as ends). Where the language of autonomy becomes prevalent, thus, humiliation (which can be minimally described as an assault on self-respect) becomes both especially visible and especially unacceptable. The humiliation involved in untouchability—which Gopal Guru has so powerfully brought out—would thus have become especially visible within a liberal framework.

That visibility would also likely have been heightened by the anxieties of the Indian upper-caste nationalists. When Samuel Johnson remarked of American revolutionaries, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” it did not have much impact on the revolutionaries—they were too ensconced in their racism, and confident in their relation to the British, for such questions to matter. Most upper-caste nationalists, traumatised by the racial humiliation they themselves experienced in colonial rule, shaped by the anxiety that they lacked ‘modern’ culture, could not share this confidence. The ‘untouchability problem’ was at least as troubling as the ‘Hindu-Muslim problem’. Maybe even more troubling—the analogy between the racial humiliation they suffered and the caste humiliation they inflicted was inescapable, and several early 20th century Indian thinkers, including Gandhi, dwelt on it.

2

We can schematically identify four different responses to this new way of organising the experience of caste discrimination—four responses that sought to reconfigure ‘untouchability’: liberal secularist, Hindutva, Gandhian and Dalit.

The liberal secularist response receives its fullest articulation in the Indian Constitution and some subsequent laws. This secularism accepts some degree of responsibility for the violence faced by the lowest castes. Hence, in addition to Article 17 of the Constitution, which abolishes untouchability, Article 16 provides for taking “special care” of the “educational and economic interests” of the Scheduled Castes, for protecting them “from social injustice and all forms of exploitation”. Or again, even as Article 25 of the Constitution guarantees that “all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion”, it goes on to say that nothing in the Article shall prevent the state from “throwing open...Hindu religious institutions of a public character to all classes and sections of Hindus”. A subsequent law, the Untouchability Offences Act of 1955, goes on to specifically prohibit restrictions on temple entry on the ground of ‘untouchability’.

Through such moves, the liberal secularist tradition names ‘untouchability’ and the humiliation it involves as always violent. And it deploys the term ‘Scheduled Castes’ to name untouchability under erasure—both acknowledging the continuing violence of untouchability, and accepting responsibility for redressing past and present violence.

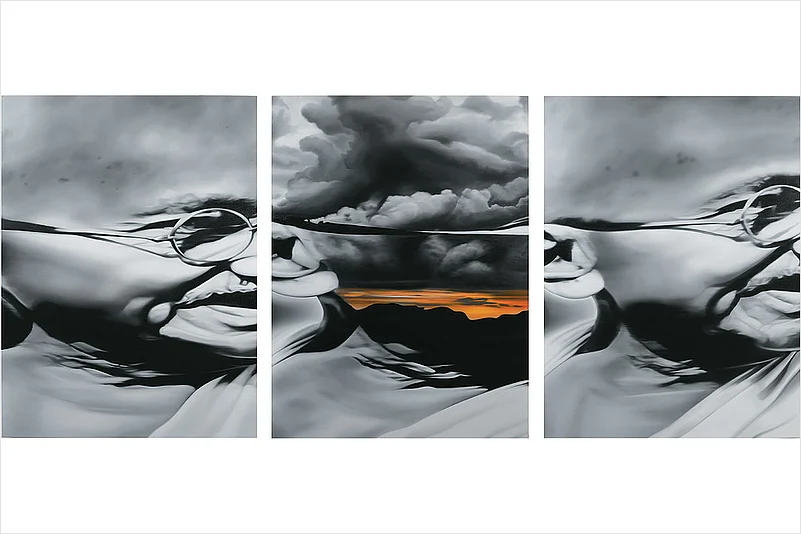

Gandhi from Kochi, oil on canvas series by Riyas Komu

Of course, liberal secularism remained blithely upper caste, not only in the way that its legal provisions were poorly implemented, but also in the way secularists often denied, minimised or remained unaware of the violence and humiliation involved in caste. Thus, caste was often framed (continuing a colonial tradition) in terms of the structural or systemic principle of hierarchy (hence, ‘caste system’), as distinct from the principle of equality that purportedly marked classes in the West. Here, untouchability (and sometimes even the proliferation of castes) was seen as a later accretion and excresence. And many secularists also idealised varnashramadharma, which was understood as a hierarchy where prohibitions on interdining or intermarriage worked to create a society based on complementarity and division of labour. Indeed, if Indian nationalists such as Nehru (and before that, colonial officials such as Henry Maine) celebrated those mythical ancient panchayats, this was surely in part because the panchayats, where representatives from various castes were presumed to have amiably conferred together, seemed to show that caste with its hierarchical complementarity was quite compatible with citizenship and even democracy.

3

To understand Hindutva, it helps to reformulate the point Ashis Nandy has often made—that Hindu nationalism is secular. The reformulation: Hindutva is a secularity without secularism. As a shorthand: secularity or secular ideology (1) understands our everyday world in terms of immanent or natural causes—that is to say, without invoking divine intervention or ‘transcendent’ causes; (2) involves forms of government that do not concern themselves with managing citizens with a view to their afterlife or transcendent goals. By contrast, secularism or secularist ideology insists additionally that citizenship or participation in public life will be only on the juridical basis of belonging to a nation-state. In other words, a citizen’s religion (and increasingly, other substantive qualities such as race, gender or ethnicity) will be private, irrelevant for determining participation in public life. Secularity is usually a condition or historical situation, secularism is usually also a project.

Much like the Zionists around the same time, V.D. Savarkar initiates a new project or programme: a secularity that rejects secularism. His greatest innovation in Essentials of Hindutva is to provide a purely secular definition of Hindus as a community. Thus, for him, Hindus could be identified not on the basis of shared belief about divinity or transcendent matters, but by four secular criteria—a common pitrubhumi or fatherland, common blood, “common Sanskriti (civilisation)” and a common punyabhumi or holy land. Even punyabhumi is secular: its object is something immanent, a land. Because Hindutva is defined by secular criteria, for Savarkar even rationalists may join the Hindu Mahasabha. But Savarkar is by no means a secularist: in the society he seeks to create, public life will exclude or marginalise those who do not belong to the community defined by these four secular criteria.

The four criteria are explicitly honed so as to exclude Muslims most effectively from the political community. But that exclusion also works by articulating a very distinctive upper-caste ideology. Two forms of Hindu nationalism were especially prominent in the early 20th century—that articulated by the RSS, and that articulated by Savarkar, who led the Hindu Mahasabha. (This distinction may not be as relevant for the present. As the political theorist Jyotirmaya Sharma pointed out in an e-mail to me, one significant change brought about by Mohan Bhagwat was the remoulding of the RSS so as to bring it closer to a Savarkarite ideology.)

In the early 20th century, the RSS aggressively affirmed caste hierarchies, and also actively defended untouchability. By contrast, Savarkar forcefully criticised untouchability. In 1939, for example, he states in his presidential address to the Mahasabha that “in public schools, conveyances, posts, services and in every aspect of public life no Hindu should be permitted to deprive other Hindus of their public rights on ground of caste untouchability alone”. Again, in 1942, he sends a message to Ambedkar’s Golden Jubilee Committee, hailing Ambedkar’s efforts to eradicate untouchability and stressing “my own persistent efforts for the last 30 years or so on my own lines to uproot untouchability”.

In practice, however, Savarkar and his Hindu Mahasabha not only did very little to actually reduce caste violence, but often systematically promoted upper-caste domination. This is not surprising. As a sociological phenomenon, the Mahasabha’s opposition to untouchability was internally conflicted: the Mahasabha and RSS had overlapping constituencies, enabled by the assumption that the RSS was concerned with ‘cultural’ activities and the Mahasabha with ‘political’ activities.

But it would be intellectually shoddy to dismiss the Savarkarite critique of untouchability only by invoking this internal contradiction. For we understand nothing of Savarkar, and certainly nothing of the Modi phenomenon, unless we recognise that a powerful stream of Hindutva is opposed to untouchability.

So our question must be: what is conceptually distinctive about Savarkar’s attacks on untouchability? What are the “my own lines” that Savarkar identifies in his felicitation of Ambedkar? What differences make Savarkar say in his 1939 presidential address that “the approach of the Hindu Sabha to the question of the removal of untouchability differs at the root from the approach of the Gandhist attempt to remove it” [italics original].

A succinct way of describing the differences could be: Hindutva is anti-untouchability, but in a way that perpetuates caste and caste hierarchies. The liberal secularist and Gandhi’s approaches are anti-untouchability, and bear the potentiality to be, in very different ways, anti-caste. Ambedkar’s critique is dismissive of anti-untouchability politics because it usually perpetuates caste hierarchies; his critique is emphatically anti-caste in a way that differs from the potentialities borne by either liberal secular traditions or Gandhi’s writing.

Consider Savarkar’s attacks on untouchability. First, in contrast to the secularist perspective, Savarkar disavows any upper-caste or social responsibility for the humiliation and violence involved in caste. Rather, he attempts to generalise and thus erase any responsibility for untouchability, for caste violence and humiliation. The 1939 address goes on to say: “It must be plainly mentioned here that even those who are at present bracketed as untouchables are themselves guilty of this sin just like those who are bracketed as touchable Hindus. For, every untouchable caste treats some other caste supposed to be inferior to it as untouchable as ruthlessly as it is treated itself by others. The sin is common to all of us and therefore let us all join hands together and be determined to remove this curse with a supreme effort” [italics original].

A common sin, then: a cultural trait for which upper castes like Savarkar need feel no particular responsibility. Here, the historical and structural violence inflicted on the lowest castes need not be acknowledged or redressed. Indeed, there is an obsessive denial of responsibility for untouchability. Symptomatically, in his last work, Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History, completed in 1963, Savarkar asserts that untouchability and other “native shackles...did never appear to be shackles or fetters to the Hindus of those times, when the Muslims had begun invading India. To them they were but the charmed amulets or protecting bands.”

He also takes issues with “those who ignorantly or maliciously blame the Peshwas for the malicious treatment given to the untouchables”, arguing that those who do so should also blame previous regimes. Likely responding implicitly to Ambedkar (whom he describes by now—1963—as a “Hindu hater” and whose “vulgar remarks on Hindu history” he attacks in the book), he assigns special blame for untouchability to “the Buddhists”, who “I should like to repeat, aggravated and not mitigated ‘Untouchability’.... The untouchables like the Chandals and others preferred the Vedic regimes as more congenial to the unrelenting and uncompromising Buddhist ones.” If in Essentials of Hindutva, Buddha and Buddhism served as a surrogate for Gandhi, now they are a surrogate for Ambedkar.

Nor, Savarkar’s argument implies, should upper castes be required to give up on practices like the prohibitions on temple entry. “[W]e should on no account molest or disrespect the sentiments of our Sanatani brothers so far as their personal freedom is concerned,” he writes. This stipulation is not innocent: it is precisely by invoking personal freedoms, by claiming that temples were not public spaces, that upper-caste nationalists fought back against the efforts to push temple entry.

Six Glorious Epochs also lists what there is to “gratefully cite” about the “caste-system”. But for the religious duties “prescribed for the particular castes and subcastes like Pariyas, Bhangis, Kolis [and] Bhils”, the “Hindu faith...would never have otherwise remained so steadfast through all these perilous centuries.” Where the book criticises caste, it is not so much for its vicious violence as for the way its “silly superstitions” weakened the possibility of a community organised around Hindutva. As the historian Vinayak Chaturvedi, who is completing a book on Savarkar, notes in an e-mail, Savarkar “is interested in abolishing untouchability not simply for the purpose of ending untouchability, but because he views it as a step closer to creating a pan-Hindu identity”.

Second, again in contrast to the secularist critique that sought to create a world of autonomous and casteless citizens (and failed to do so in India, as it has everywhere; though, to broach a theme which there is no space to discuss here, this failure is perhaps its greatest gift), Savarkar’s attacks on untouchability reinstitute a caste hierarchy—now in the form of Hindutva.

This reinstitution is not immediately apparent. Essentials of Hindutva insists that all Hindus, whether Brahmin or Chandal, are one because of the four elements they share (the secular criteria noted earlier) and that differences between them are irrelevant compared to this shared identity. In its explicit arguments, thus, Essentials of Hindutva dismisses caste entirely. And on a quick reading, it might seem that caste survives here primarily in the sense that the substantive content of Hindutva is upper caste, that Hindutva imposes upper-caste norms on lower castes.

But there is also a more structural or constitutive sense in which Hindutva modernises and reinstitutes caste. Recall the way Savarkar draws on the secular distinction between public and private—insisting, for instance, that untouchability and caste differences in public life will not be allowed. The implication, of course, is that caste differences are allowed in private life.Thus Savarkar says his 1939 address: “Our Sanatani brothers may rest assured that barring the fundamental rights to which every citizen is entitled in public life, the Hindu Mahasabha will always refrain from having recourse to law to thrust any religious reform…even in the case of untouchability.”

The problem, however, is that private life is never only private. In addition to the public realm of citizenship and the private realm of individual relations and choice, there is also a third realm—what Hannah Arendt has called the realm of society, “that curious, somewhat hybrid realm between the political and the private”, which has discrimination along various lines (such as “profession, income, and ethnic origin”) as its organising principle. Private life in other words is often unavoidably social.

This need not necessarily be bad—some groups that are simultaneously private and social may enable a vigorous citizenship. But caste, constitutively founded on relations of domination and subordination, would necessarily have the most vicious and violent effects in both social and political realms. And Hindutva, to the extent that it vigorously defends a private space for caste, aggressively promotes this violence.

Among the most prominent Indian leaders of the mid- and early 20th century, only Ambedkar worked with a distinction between the private, public and social. This is what allowed him to pose the “social question” in the distinctive way that he did. More than anybody else, he realised the importance of redefining the private in such a way as to reduce the effectivity of forms of domination such as those involved in caste and gender. Hence, perhaps, the limitations of the Indian Constitution on religion as a private right. Some years later, it was again at stake in his drafts in the early 1950s of the Hindu Code Bill. This time, the Mahasabhaites and upper-caste Congressmen fought back more successfully, watering down the bill so much that he thought it better to resign.

4

While Nehru and Savarkar respond to the “untouchability problem” with two opposed secular programmes, Gandhi offers a religious response. Here I wish to stress only one aspect of religion as a ‘concept’: the nature of its responsibility. Ambedkar remarks in Annihilation of Caste that responsibility is the “essence of a truly religious act”. We could draw out this observation by asking further: how is responsibility more the essence of a truly religious act than of a truly secular act?

Very simply put, one might say: secular responsibility engages, at its best, in a rational division and distribution of responsibility; it parcels out responsibility between various actors. A secular analysis reveals, always, that no one person or entity is responsible for an act. Secular responsibility is never borne singularly (though secular guilt, at least as a juridical category, is borne singularly: for example, while upper castes bear an inescapable responsibility for all violence against lower castes, their guilt must be determined in each singular case). Religious responsibility, by contrast, is sole or absolute for every individual bearing it. Religious responsibility can be shared, not parcelled out—even when shared, it does not in the least reduce the responsibility of the others bearing it.

9/11/2016, oil on canvas by Riyas Komu

This assumption of sole responsibility is the crux of Gandhi’s politics. For instance, in Hind Swaraj the Editor says: “The English have not taken India; we have given it to them. They are not in India because of their strength, but because we keep them.” As a secular statement, this is sheer nonsense. Indians certainly colluded in British rule, but equally certainly the English were in India because of their strength. From a religious perspective, however, Gandhi’s statement makes perfect sense: even if the English were in India because of their strength, that cannot in the slightest obscure the Indian responsibility for it. Moreover, this is also a sole responsibility—while the English too may be responsible for it, the responsibility of others does not diminish the responsibility of Indians.

Again, satyagraha is nothing but the assumption of sole responsibility. Satyagrahis say they are responsible for the violence they face or participate in; their responsibility makes them resort to satyagraha. Through satyagraha, they hope to bring their interlocutors to the responsibility that the interlocutors have forgotten. But if they fail, then it is not because of any shortcoming of the interlocutors; it is rather because the satyagrahis have not assumed their responsibility vigorously enough. Indeed, it is of the nature of sole responsibility that it cannot knowably be discharged: those bearing it remain aware only of their inadequacy to meet it.

5

Religious responsibility is at work also in Gandhi’s term Harijan. He comes to that term somewhere around 1921, but it becomes a serious concept for him only around 1931. He writes that year: “It was a word used by the great saint Narasinha Mehta, who…defied the whole community by claiming the ‘untouchables’ as his own. I am delighted to adopt that word, which is sanctified by having been used by such a great saint, but it has for me a deeper meaning than you may imagine. The ‘untouchable’, to me, is, compared to us, really a ‘Harijana’—a man of God, and we are ‘Durjana’ (men of evil). For whilst the ‘untouchable’ has toiled and moiled and dirtied his hands so that we may live in comfort and cleanliness, we have delighted in suppressing him. We are solely responsible [italics added] for all the shortcomings and faults that we lay at the door of these untouchables. It is still open to us to be Harijana ourselves, but we can only do so by heartily repenting of our sin against them.”

“We are solely responsible…” It is the soleness of this responsibility, more than the term’s meaning, which promises to make ‘Harijan’ a religious word.

But in the way this responsibility is worked out in Gandhi’s politics, to extend the arguments I make in Unconditional Equality, soleness is abandoned and the term ‘Harijan’ becomes violent in its distinctive way.

First, that responsibility does not remain sole. The Harijan Seva Sanghs, which work for the ‘uplift’ of the Harijans, impart an education steeped in upper-caste norms, such as the injunctions against meat-eating. These norms at least implicitly perpetuate the pervasive upper-caste assumption that lower-caste practices are also responsible for caste violence.

Second, contrast the situation here with the Editor’s claim that Indians were solely responsible for the presence of the British in India. There the Indians were the oppressed and the British were the oppressors. Faced with this racial humiliation, Gandhi stressed that it was impossible for the British to give swaraj to Indians even if they wished to; it would be swaraj only if Indians took it themselves. Indians are solely responsible, thus, not only for the British being in India, but also for getting swaraj from the British. That sole responsibility is carried out through satyagraha. And where satyagraha is successful, sole responsibility is shared—the British too recognise their responsibility and relinquish their hold over India. Satyagraha is the sharing of, or more precisely, giving and receiving of, sole responsibility.

But with the untouchables, things are flipped around.

Now Gandhi’s position is analogous to the British. (This he is aware of—he finds it apposite that the upper castes are humiliated by the British just as they humiliate the untouchables.) Should it not then be impossible for the upper castes to give freedom from caste oppression to untouchables? Should not the untouchables themselves take their freedom from upper castes? In other words, even if Gandhi’s response, as an upper-caste figure religiously accepting responsibility for caste violence, is to render the untouchable into the Harijan, should not that very rendering take the form of enabling Harijans to offer satyagraha against the upper castes? But Gandhi refuses to countenance this: he asserts on several occasions that Harijans must not offer satyagraha in the sense of passive resistance to upper castes.

Third, and relatedly, to stop being durjan and become Harijan, satyagrahis must atone for the sin of untouchability through what Gandhi on occasion calls “repentance”. If this repentance is to remain religious (which is to say: if the responsibility for untouchability is to remain absolute), then the satyagrahi can never repent enough, and therefore can never claim identity with the Harijan. Identity remains an impossible but necessary ideal. But Gandhi repeatedly claims identity with the Harijans—in 1931 during the Round Table Conference, for instance, he declares that if Dr Ambedkar was the “real representative” of the Depressed Classes, “I should have withdrawn.… I repudiate his claim to represent them. I am the representative of the depressed classes.” By so claiming adequate repentance, Gandhi again violates the religious problematic he introduced with the term Harijan.

Fourth, given all this, the term Harijan was often disempowering for the very communities so named. How and why this was so has been summed up powerfully by the late D.R. Nagaraj in his book The Flaming Feet: “In the intensely moving romantic tragedy of self-purification...there was scope for only one hero, that is, Gandhiji himself.”

“Babasaheb had no other option but to reject the Gandhian model. He had realised that this model had successfully transformed Harijans as objects in a ritual of self-purification, the ritual being performed by those who had larger heroic notions of their individual selves. In the theatre of history, in a play of such a script, the untouchables would never become heroes in their own right, they are just mirrors for a hero to look at his own existentialist angst and despair, maybe even glory.”

Nagaraj also provides a brilliantly insightful account of that moment in Gandhi’s May 1933 fast when Mahadev Desai tries to persuade a Harijan boy to come to offer orange juice to Gandhi to break the fast. The boy, Desai notes, never turned up. Why not? speculates Nagaraj. And he suggests: “The Harijan boy who took a decision not to keep the appointment with Gandhiji was reborn as a Dalit youth.”

In popular usage, the term Harijan took longer to die. Till more ethnographies and histories become available, we can only speculate why for several decades so many Dalit groups assumed that name for themselves. Was ‘Harijan’, however profoundly inadequate as an act of upper-caste responsibility, nevertheless less violent than those available in other upper-caste traditions such as the secularist ‘Scheduled Castes’ or Hindutva’s disowning of any responsibility? Whatever the reason, by the 1960s the violence of the name ‘Harijan’ was both greater and more visible, and more and more Harijans died to be reborn as Dalits.

Such rebirth, need one say, was also the death of a certain Gandhi—call him the theological Gandhi, or Gandhi the Father of the Nation. I draw on the term theological to denote the kind of religion where practitioners disown “sole responsibility”. Theological religion institutes instead a division and distribution of responsibility. As this description suggests, theological religion has always been around—it is at play, for example, whenever worshippers assign to divinities a responsibility separated from their own. Liberal secularism killed the theological gods (or at least reduced their power greatly), but it did so only in order to institute a more rational and systematic division and distribution of responsibility. In this sense, liberal secularism conserved theology even as it killed God.

6

The second yes: the term Harijan also probably dies in another sense, this time because of a radical assumption of sole responsibility. Already, in an essay in 1921 describing his abandonment of the belief that he was “a citizen of the Empire”, Gandhi draws an analogy with the untouchables: “The whole situation is now changed for me.... I can take no pride in calling the empire mine or describing myself as a citizen. On the contrary, I fully realise that I am a pariah untouchable of the empire. I must, therefore, constantly pray for its radical reconstruction or total destruction, even as a Hindu pariah would be fully justified in so praying about Hinduism or Hindu society.” In an interview in 1927, he goes further: “If varnashrama goes to the dogs in the removal of untouchability, I shall not shed a tear.”

This position parallels in striking ways Ambedkar’s INSistence that the destruction of untouchability requires the destruction of varnadharma. Unlike Ambedkar, of course, Gandhi comes to his argument most reluctantly and continues to recoil from it all his life.

And yet, by the late 1930s, as he himself assumes the identity of a Bhangi more emphatically, his prayers become ever more paradoxical: he must pray for varnadharma by seeking its death. In this self-sacrifice, varnadharma must be displaced by what untouchables put in its place—“they will someday or the other dictate their terms”. From this perspective, should not the quasi-concept ‘Harijan’ seek to sacrifice itself to that other quasi-concept, the Dalit? Is not this very death the destiny ‘Harijan’ must seek to receive from ‘Dalit?’ Is an absolute responsibility assumed in the peculiar death of the term ‘Harijan’? The very nature of absolute responsibility—its unknowability—precludes an answer to this question.

7

With the death of the term Harijan in the second sense, a second Gandhi also dies—call him the mystical Gandhi. But this mystical Gandhi does not just die. In his very death, he flickers into life, becomes a spectral force.

I draw on the term mystical to refer to those moments when religion comes to be seized by “sole responsibility”. This is not a new Gandhi. Indeed, this is perhaps the oldest Gandhi. His mysticism is what is most intriguing in Gandhi, and what he calls pure satyagraha is nothing but mysticism. Moreover, his is a political mysticism: unlike many mystics who seek freedom by shedding social bonds, Gandhi’s mysticism concerns a freedom in society. If so many generations have found Gandhi so good to think with, this may well be because there erupts unpredictably in his writing this political mysticism. I say unpredictably because this mysticism is often obscured from Gandhi himself, and we can elicit it primarily by reading him carefully, sometimes against the grain of his explicit assertions.

For now, I want to stress just one element of his political mysticism—its distinctive finitude or vulnerability.

Secularity as a condition is not unfamiliar with vulnerability. As Simona Sawhney writes in an e-mail, “in the experience of the secular, … there is a glimmer—often no more than that—of being skyless. It is, or can be, an earth-shattering glimmer.... [But] this glimmer usually gives way, right away and imperceptibly (and this is not even a temporal movement), to another sky.… One starts living under its shade and gaze, as one lived under the shade and gaze of God.”

These new and immanent skies, as they secure themselves against vulnerability, take many forms: great men, laws of history, the scientific truths of nature, the nation and so on. For those who grew up taking the new secular skies for granted, the experience of vulnerability may be very faint indeed.

Liberal secularism is one influential framework that organises the new skies. Its invulnerability is institutionalised primarily through the assumption that individuals own themselves and that inalienable rights, qualified only by national interest, flow from this ownership. But liberal secularism also simultaneously institutionalises vulnerability: it insists that citizenship requires questioning, that citizenship requires the exercise of a reason that keeps all its practices open to critique—in a word, vulnerable. Symptomatic of this institutionalisation of the question is the prominent role that universities often play in secularist societies. Universities institutionalise two kinds of questions: the unanswerable ones pursued largely by the humanities, and the answerable ones pursued largely by the sciences and social sciences.

Of course, as many have argued since at least Marx, the distortions of the public realm ensure that critical reason does not actually rule in the secularist societies. Moreover, critical reason cannot actually rule, for that would be a paradox: how can vulnerability be institutionalised as sovereign in an order organised around the invulnerability of self-ownership? Indeed, can vulnerability be institutionalised?

A second framework that organises the new skies is exemplified in Hindutva and Zionism. This programmatic secularity accepts the language of ownership, but privileges the ownership exercised by nation and religion. It takes fright also at even the limited institutional space that liberal secularism provides for vulnerability, for the question. This programmatic secularity epitomises what it means to become incapable of religion as vulnerability and finitude. It is frightened especially by unanswerable questions, and this fright often takes the form of vicious rage at the humanities. The only questions it can tolerate are answerable ones, such as those involved in the sciences, or the social sciences narrowly defined. But answerable questions wither unless nourished by unanswerable ones, just as unanswerable questions wither without answerable ones.

8

Gandhi’s brilliance, the immense fearlessness of his thinking, lay in clinging to the glimmer of skylessness that accompanied the thunderclap of secularity.

The glimmer of skylessness is always an experience of vulnerability. Political mysticism clings to that experience by practising a politics of finitude or vulnerability. Vulnerability presents us with another equality, one very different from the equality of self-ownership. While the latter is exclusionary, the former is organised around interdependence. Also, while the latter is limited to some humans, vulnerability is constitutive of all being everywhere. Pursuing this other equality, political mysticism therefore seeks to conserve and nourish vulnerability.

But what vulnerability is to be conserved? Clearly, not privative vulnerability—not vulnerability as disempowerment: as oppression, humiliation, deprivation or exploitation, for example. To ask the already disempowered to further disempower themselves—this would be very violent. Rather, what is to be conserved is a vulnerability that, without institutionalising self-ownership, empowers those at the margins of society.

Symptomatic of Gandhi’s efforts to think this other equality and its vulnerability are some of the phrases he draws on to describe satyagraha—friendship with death, living by dying, and so on. Death is, of course, the starkest name for vulnerability. These phrases suggest that death is not an end, but rather an opening. Of course, nothing is more difficult to think than this friendship with death. Repeatedly, his formulations and practices about it become theological. But a proper friendship with death, dare one say, would be mystical. And in such a friendship, death is also the beginning. At their most thoughtful, thus, “friendship with death” and similar phrases name not a heroic death or self-sacrifice, but the everyday embrace of vulnerability as a politics, a life. Friendship with death conserves the equality of all being by “self-surrender”, by relinquishing ownership of oneself. In other words, satyagrahis must strive to fight injustice in a way that remains vulnerable to those whom they struggle against, with or for.

By way of a coda, I should add also: satyagraha is only one way of thinking this other equality and the politics of vulnerability. For example, we usually oppose Ambedkar to the theological Gandhi. This is correct and essential, but it is not enough. For Ambedkar too is engaged, in a very different way, in a politics of vulnerability. Unlike Gandhi, he refuses to relinquish liberal secularism—hence his involvement in the Constitution. But he finds the Constitution profoundly inadequate—hence his conversion to Buddhism even as he is instituting a liberal-secular order. Because of this doubled commitment, I have suggested elsewhere, it may be fruitful to think of Ambedkar as a practitioner of radical secularism. I say ‘radical’ here in the sense offered by its etymology (radix, roots)—to indicate that which goes to the roots, in order to reroot or uproot. Unlike liberal secularism, radical secularism does not securitise its questions; it does not make itself invulnerable; it clings to the glimmer of skylessness, remaining open even to ‘religion’. What does Ambedkar’s radical secularism involve? What is its relation to—its affinities with and differences from—the politics of the mystical Gandhi? For those of us invested in a politics that opposes Hindutva while remaining chary of liberal secularism, such questions may be unavoidable.

(Ajay Skaria teaches at the University of Minnesota. His most recent book is Unconditional Equality: Gandhi’s Religion of Resistance. Excerpts from a conversation about the book are available here; the full transcript of the conversation is available here)