The Land of Blue Mountains

My grandmother used to tell us a bedtime story of how her village, Hualtu, was burnt down and all the villagers were displaced. They had to move to a new grouping centre called Baktawng village in 1967. This was when the Indian government under Indira Gandhi introduced ‘‘grouping of villages’’ as a counter measure to weaken the MNF freedom movement. The trouble lasted 20 years until a Memorandum of Understanding (also known as the Mizo Peace Accord) was signed in 1986. Both my grandparents’ and my parents’ generations’ imagery of the Indian State was quite violent as they had to face many challenges in the midst of the brutal confrontation between the Indian security forces and the Mizo National Front (MNF) rebels. After my grandfather—a founder member of the United Mizo Freedom Organisation (UMFO)—passed away in 1998, I went through his old files stored in a wooden box. There was an interesting memo in there which highlights the dilemmas of the people in the erstwwhile Lushai Hills on the brink of Indian independence in 1946. This made me understand the sense of identity and belonging that the people of Mizoram have felt since the colonial period, which could well have been the predecessor of the MNF movement that came two decades later.

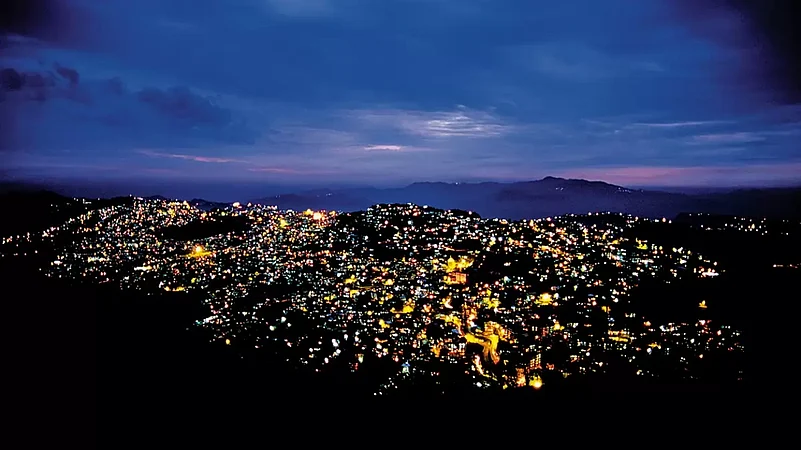

Mizoram—a hilly state in the north-eastern corner of India sandwiched between Myanmar and Bangladesh—is known for its turbulent history due to the violent freedom struggle of the people under the banner of the MNF. The present state of Mizoram came under British occupation as the Lushai Hills in 1890.

After the Chin-Lushai Expedition of 1889-90, the Hills were formally declared a part of British India in 1895. Initially, the British divided the Hills into North Lushai Hills and the South Lushai Hills but later amalgamated the two, and in 1898, constituted the Lushai Hills district under the province of Assam. Prior to the British annexation, the land belonged to the chiefs. The British continued to protect the institution of chiefs to gain the people’s allegiance.

Endless Search for Identity

The early recorded history of the Mizo and different sub-tribes within it is based on legends, traditions, customs and beliefs. These provide ethnographers, historians and scholars raw material for the study of their migration and early settlement in the region. There is a common belief among the Mizo that their ancestors emigrated from a mythical cave called ‘Chhinglung.’ A constant quest for multiple identities may never have a definite answer. Race, ethnicity, tribes, gender, and even nationality play a critical role in the realms of both individual and collective pursuits. This endless search for identity and security helped shape the evolution of Mizo society.

Mizoram was granted the status of Union Territory in 1972, and then statehood after the historic Mizo Accord, signed between the former rebel group the MNF and the Government of India.

The Birth of Mizo Union

The development of political consciousness and socialisation processes among the tribal societies in Northeast India, including Mizoram, can be attributed to the impact of colonialism. Various factors and events influenced them. These include the introduction of western education, spread of Christianity, the international political environment (especially WWI and II), and the uncertain political situation in the region on the brink of Indian independence. As a result of the growing political consciousness, the educated youths formed a political party named Mizo Union in 1946 to voice people’s aspirations and raise several political demands, including the abolition of traditional chieftainship.

After being a full-fledged state of the Indian Union for the past 36 years, the question of identity and belonging still occupies a significant place in the collective imagination of the people of Mizoram. The crisis in Myanmar, Bangladesh and the neighbouring state of Manipur brings people across borders and compels them to reflect upon their physical existence as communities with a shared cultural heritage, irrespective of the artificial divisions that have sprung up since the colonial cartographic arrangement of the region separating these communities in the Indo-Myanmar borderlands.

C. Zonunmawia is a political analyst and commentator

(This appeared in the print as 'Mizoram Diary')