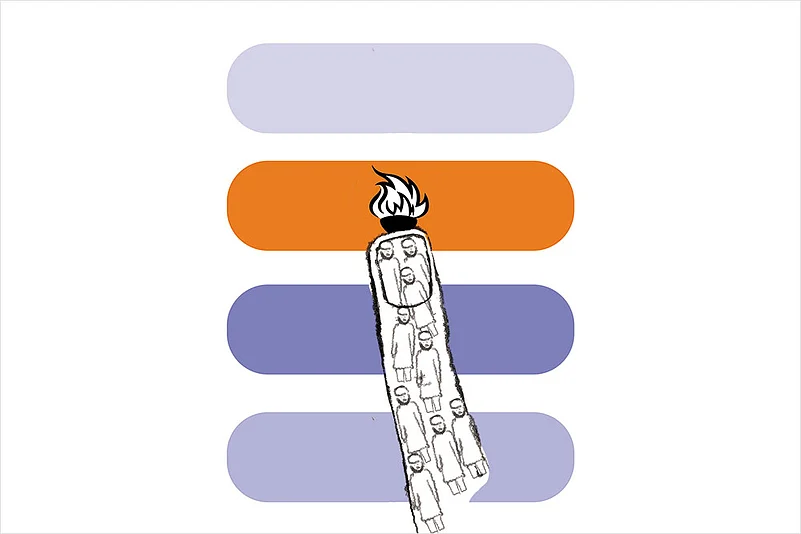

In 1993, communal riots engulfed Bombay following the demolition of the Babri Masjid. The burning of Radhabai chawl in suburban Jogeshwari, where a Hindu family was locked inside and set ablaze, became a flashpoint that fuelled retaliatory violence against the city’s Muslims.

Mobs of ‘anguished’ Hindu youth, led by Bal Thackeray’s Shiv Sena, ran amok— killing, looting and committing arson against Muslims and their properties— in a ‘spontaneous reaction’ to the Jogeshwari carnage. Thackeray directed his vitriol against ‘anti-national Muslims’, provoking further violence in Muslim-dominated areas, branding the Shiv Sena as the most fearsome political outfit vis-à-vis Muslims.

Thirty years on, politics has come full circle.

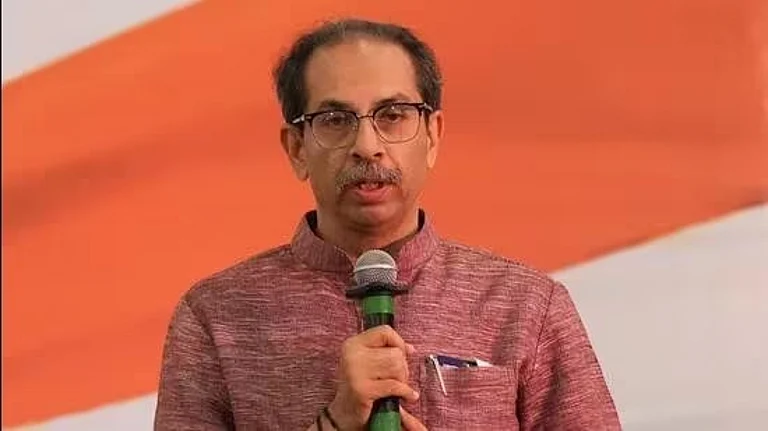

Following the death of Bal Thackeray, the rise of his moderate-minded son Uddhav to the party’s helm and the emergence of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—which appears to have wrested the mantle of hardcore Hindutva politics from the Sena—the equation between the regional saffron party and Muslims in Maharashtra seems to have thawed considerably.

Thackeray’s grandson, Aditya, is now campaigning for Haroon Khan, a Muslim candidate contesting the upcoming state assembly elections on a Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray) ticket. Khan hails from Jogeshwari and is contesting the polls from the Versova constituency in northwest Mumbai.

Khan’s slogan, “Ekta ka raaj chalega, Hindu-Muslim saath chalega,” aims to promote communal harmony and development. Targeting both upscale Versova and Oshiwara and the slum settlements, Khan seeks support from the constituency’s significant minority voter base.

“I am a Muslim and a Sainik,” says Khan, whose three decades of party work earned him a 2024 assembly poll candidacy. His Facebook displays a photo of Thackeray embracing him, captioned ‘Balasahebancha Haroon’. “Balasaheb had promised me a ticket whenever my constituency was open for general candidates. This time there was no OBC or women’s reservation, so Uddhav saheb has kept his (father’s) word,” he says. Khan joined the Sena in the 90s, a time when most Muslims distanced themselves from the party. “The Shiv Sena was the only party which could stop the riots (at the time). We took out a huge rally for peace in Hindu and Muslim areas,” he says.

Sabir Shaikh from Bhiwandi was the Sena’s first Muslim MLA and served as labour minister in the Sena-BJP government in 1995. Before him, Congressman A.R. Antulay, a Konkani Muslim, was the first chief minister of Maharashtra from the minority community, holding office from June 1980 to January 1982.

The 1992-93 riots led to a significant shift in Muslim support away from the Congress, recalls Sanjay Patil, an academic at Mumbai University, researching elections and politics.

Disappointed by the Congress’s failure to act against Sena and Sangh workers during the Bombay riots, Muslims voted against it. In 1995, the Congress won just 80 seats, enabling the BJP-Sena alliance to seize power.

Meanwhile, the Shiv Sena has significantly evolved from its hardline Hindutva stance. Uddhav Thackeray’s secular approach has resonated with Muslims, creating a sense of trust. Patil notes, “The way Uddhav has remodelled himself and the Sena, calling for the protection of Muslims, he has become a safe choice for the community.”

As the Shiv Sena’s only Muslim candidate in the assembly elections, Khan’s nomination seems to have rattled the BJP. In a veiled reference against Khan’s religious identity, Deputy Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis urged voters at a rally in Oshiwara to wage ‘dharma yuddha’ (religious war) in order to counter ‘vote jihad’. Khan is contesting against the BJP’s Bharti Lavekar, a two-time MLA from Versova.

Interestingly, Khan had campaigned in support of Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections, when the undivided Shiv Sena and the BJP were in alliance. He says he is unperturbed by such overtly communal statements by his opponents.

The BJP has also opposed Nawab Malik’s candidacy for Mankhurd Shivaji Nagar, nominated by alliance partner NCP (Ajit Pawar), despite objections from its elder ally. Malik, arrested in 2022 for alleged ties with Dawood Ibrahim in a money laundering case, got bail on medical grounds last July. Other notable Muslim candidates include Fahad Ahmed (NCP–Sharad Pawar) from Anushakti Nagar, Najeeb Mulla (NCP–Ajit Pawar) from Mumbra and Abdul Sattar (Shiv Sena –Shinde) from Sillod.

Muslims make up about 12 per cent of Maharashtra’s population, yet their representation in the assembly has steadily declined, peaking in 1999 with 13 MLAs. In the upcoming elections, the AIMIM has fielded 13 Muslim candidates, Congress nine, NCP (Ajit Pawar) five, and others fewer. The BJP has not fielded any Muslim candidates—instead it has ramped up a polarising campaign. Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath’s slogan “batenge toh katenge” (we will be slaughtered if we are divided) and Amit Shah’s anti-conversion law promise have also heightened Muslim voter concerns.

The aggressive anti-minority rhetoric, including terms like ‘vote jihad’ and ‘love jihad’, has prompted the BJP’s alliance leaders like Ajit Pawar and Pankaja Munde to distance themselves, mindful of their substantial Muslim vote bank in Baramati and Beed, respectively.

The BJP has leveraged Hindutva rhetoric by roping in leaders like Adityanath, Tejasvi Surya, Madhavi Latha and Anurag Thakur. They are leading rallies across Maharashtra, accusing the MVA of indulging in ‘vote jihad’. This sharp anti-Muslim stance aimed to consolidate Hindu votes has unsettled the Mahayuti alliance and strengthened Muslim unity, says Patil.

The BJP’s image as an anti-Muslim party appears to have decisively shifted the sensitivities of the minority community towards the Opposition, the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) bloc, comprising the Congress, the Shiv Sena (UBT) and the NCP (Sharad Pawar).

Over the last two-and-a-half years, Maharashtra has witnessed a surge in anti-Muslim atrocities, hate speeches and Hindutva rallies against ‘love jihad’ under the BJP-led Mahayuti coalition. Incidents like mob lynching, vandalism of mosques and assaults on elderly, beard-sporting Muslims have heightened concerns about the safety of the minority community.

The buildup, combined with the charged electoral rhetoric by leaders from the Shinde Sena and the BJP, has for the first time post-1995, resulted in the consolidation of the Muslim votes in Maharashtra. Muslim leaders and activists from umbrella organisations like the Marathi Muslim Seva Mahasangh (MMSM), the Maharashtra Democratic Forum (MDF) and the Maharashtra chapter of the All India Ulema Board have backed the MVA bloc. They’ve called for action against hate speech and protection of minority rights. The BJP has amplified its ‘vote jihad’ narrative, accusing the MVA of pandering to Muslim identity. The original sons-of-the-soil Marathi-speaking Muslims, with strong regional ties, are key in nearly 60 constituencies.

“Muslims are coming together because it is clear to us that the BJP wants to infringe upon our constitutional rights. Their polarising agenda has disturbed social security in Maharashtra (for) all minorities and Dalits. Our first priority is to vote for those promoting communal harmony,” says Dr Anwar Siddiqui, in charge of the MDF from Vidarbha region.

The MDF has released a five-point manifesto, which includes a demand to enact a law to prevent hate speeches.

Across Maharashtra, the MDF’s local activists are networking among voters to create awareness about candidates, their ideology and their action plan. They are also helping citizens in Dalit and Muslim settlements with voter ID cards and encouraging them to exercise their electoral rights.

“Based on the ground realities, we are either supporting candidates from the MVA or independent candidates. In areas where we don’t have suitable candidates, we will practice NOTA (none of the above). But we have decided to not vote for the BJP as we believe it is a fascist organisation,” says Siddiqui.

In the coastal belt of Konkan adjoining the Mumbai and Raigad divisions, Konkani Muslims—estimated to be around 50 lakh—are actively campaigning for the MVA’s candidates—all Hindus. “We are Konkani first, then Muslim or Hindu. We believe in Phule-Shahu-Ambedkar’s ideology. But the BJP’s politics has created a division among Hindus and Muslims. It has created fear among our community,” says Kamal Mandlekar, secretary, MMSM, Konkan region.

Konkan has been a traditional stronghold of the Shiv Sena, but after the party split, the original faction led by Uddhav Thackeray is at risk of being wiped out. In the recent Lok Sabha election, Thackeray’s Sena heavily lost to the ruling alliance partners NCP (Ajit Pawar) and the BJP.

The BJP’s attempt to build a base in Konkan by replacing Thackeray’s Sena is led by MP Narayan Rane and his son Nitesh Rane, the party’s MLA candidate from Kankavli constituency, where the family has a stronghold.

After Nitesh Rane quit the Congress and joined the BJP in 2019, he appears to have cottoned on to the party’s anti-Muslim agenda, even making inflammatory remarks allegedly threatening genocide against the Muslims.

Mandlekar alleges that the BJP has given Rane a free hand to trigger communal flashpoints, which have driven Konkani Muslims away from the party. Notably, in 2014, the MMSM, too, had supported Modi’s bid for prime ministership but soon felt alienated by the BJP’s anti-Muslim agenda. The front had even presented the state BJP leadership with a Muslim charter of demands, based on recommendations from past government reports and commissions aimed at improving the socio-economic conditions of Muslims. “There was a strong BJP wave and we thought they will help us with education and jobs for Muslims, but their policies were the complete opposite,” says Mandlekar.

“Bal Thackeray never abused local Muslims. We support Uddhav Thackeray’s Hindutva as he talks of development for all,” he adds.

The vote bank of Muslims and Dalits, who together make up 25 per cent of the population, is crucial in shifting the balance of power in the state. Poll analysts indicate that during the Lok Sabha election, both communities strongly supported the Congress-led INDIA bloc, contributing significantly to the victory of nearly 30 MVA candidates.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Siddiqui is certain that Muslims and Dalits will play an equally significant role in influencing voter turnout in the assembly elections. “Civil society and minority votes saved the Congress from going into a coma in Maharashtra. Their participation was essential in bringing about the political transformation,” he points out.