This story was published as part of Outlook's 11 November, 2024 magazine issue titled 'Whitewash'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

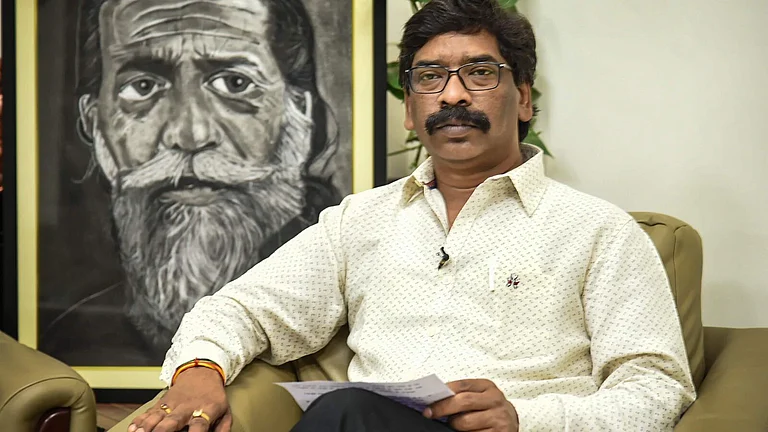

The elder’s bushy beard is silver-grey, the son’s has some pepper in it. The father is in a close-fitting white kurta, the son in a loose, bright mauve one. This photo of Jharkhand Chief Minister Hemant Soren seeking the blessings of his father Dishom Shibu Soren, popularly called Guruji, before the elections heat up in the state got some 3,000 likes in three minutes on Instagram. The father-son duo knows the power of this image.

When Hemant Soren was arrested in February this year for his alleged role in a land scam, a large-size banner came across Jharkhand’s capital Ranchi, carrying similar photos; to drill it into the people that the man going to jail was the son of Guruji, the architect of the Jharkhand statehood movement. The banner also carried the slogan—Jharkhand Jhukega Nahi (Jharkhand will not bow down), a nod to the resilience of a people who never gave in, even under British rule.

This pride in the people’s resilience and nostalgia of the struggle for statehood are once again the major themes in these elections for the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM). The distinction between the indigenous and outsiders (commonly known as diku) is gradually getting delineated. “They come from outside of the state. They don’t know our culture, language, or spirituality. They try to break us. But we will never let it happen,” says Kalpana Soren, Hemant Soren’s wife and MLA from Gandey.

For her, the ‘outsider’ is the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). For the BJP, the ‘outsider’ is the alleged Bangladeshi illegal immigrant. “Infiltrators are the vote bank of Lalu Prasad’s RJD, Rahul baba’s Congress and Hemant Soren’s JMM. I promise to drive out illegal immigrants. The time has come to show the corrupt JMM dispensation the exit door. We want to change Jharkhand,” says Union Home Minister Amit Shah at a rally in Sahibganj, marking “rampant infiltration” as one of the major issues of the state.

Identity Question

The JMM started writing its electoral script a year after it came to power with a comfortable majority. In 2020, the Hemant Soren government passed the Sarna code bill, seeking a separate religious column for Adivasis in the census. He also asked the central government to put it in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution to avoid judicial scrutiny. But the bill got stuck there. The BJP says Adivasis are Hindus with a few different cultural attributes. While responding to a question in Parliament, Union Minister of Law and Social Justice Arjun Ram Meghwal said that the Adivasis have been included as persons professing the Hindu religion in the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955.

For Kalpana Soren, the ‘outsider’ is the BJP. For the BJP, the ‘outsider’ is the Bangladeshi illegal immigrant.

In the census of 1901 and 1911, the British had a separate column for Adivasis under the title ‘animists’. In 1921, they were placed under the column of ‘tribal religion’. From the next census onwards, this distinction was discontinued. In the 2011 census, more than 40 lakh Adivasis opted for the option ‘Others’, further expanding its political contours.

The BJP never accepted this distinction. “Birsa Munda’s mentor in the early 1890s, after he shunned Christianity and walked out the Chaibasa Missionary School, was a Vaishnavite preacher, Anand Panrai,” BJP leader Tuhin Sinha was quoted as saying. According to him, Panrai taught the Gita and the Mahabharata to train Birsa Munda and that led to his spiritual transformation.

The JMM always traced their legacy from Birsa Munda and other Adivasi icons. “They couldn’t stand Adivasis riding SUVs; they want us to go back to jungle,” said Hemant Soren a day after his arrest. These continuous assertions of Adivasi identity helped them in the Lok Sabha elections, and they are eying the 26 per cent Adivasi votes that will play a determining role in the upcoming Assembly elections.

However, the JMM also tried to woo the OBC and the SC communities through the bill that sought to increase the reservation for these communities from 14 per cent to 27 per cent and 10 per cent to 12 per cent, respectively, in 2023, but the Jharkhand Governor sent it back, citing legal limitations. The Soren government also tried to implement the domicile policy that was supposed to determine ‘who is a Jharkhandi’ as per the 1932 land records, for special privileges for the locals in government jobs. The Governor returned this bill, too, for reconsideration.

Fear of ‘Others’

In contrast to the JMM, the BJP has brought in the narratives of Bangladeshi infiltration in the Santhal Pargana region—mostly in the Muslim-dominated districts of Pakur and Sahibganj. To bring the focus back on the NRC and ‘Bangladeshi infiltrators’, the BJP has given the electoral charge to Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma and Union Agricultural Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan. Sarma is well-versed in the politics of ‘outsider-insider’ in his home state. Though the politics of Assam is totally different from Jharkhand, the question of indigeneity and the invasive outsiders are similar.

During the statehood movement of Jharkhand, the term ‘diku’ had been used against those from northern Bihar who allegedly took away their resources. The word, however, changed its meaning through time. Later, it came to include people from West Bengal and northern India. The BJP changed this term to ‘ghuspethiya’ and invoked the fear of Bangladeshis who are allegedly engaged in both ‘land jihad and love jihad’. Countering the claims of infiltrators, civil society organisations like the Janadhikar Mahasabha showed that none of the cases was based on ground reality. The cases of conflict between Adivasis and Muslims are mostly local in nature and have nothing to do with the Bangladeshi infiltrators, say the civil society reports. Siraj Dutta, who was part of the team, says: “All of the incidents regarding the Bangladeshi infiltrators are actually local issues. We visited the villages and asked them whether they ever knew of the Bangladesh infiltrators. Most of them said that they got to know it from social media.”

Muslims in this region are Bangla Bhashi, not Bangladeshi. Some of them have been staying in the Santhal Pargana region since Sher Shah’s time while others have come from West Bengal, Bihar, and other places. The central government has told the High Court that there are no Bangladeshis. “The Election Commission even formed a committee and mentioned that there are no Bangladeshis there. It is just a political issue,” Dutta adds.

Agrees Shamim S Ali, a Jharkhand-based Muslim activist. “There is no Bangladeshi; in fact, one can find the Bangladeshi Hindu infiltrators who have acquired 2,500 bighas of land near the river. The government in its submission to the court, though, has said multiple times that Bangladeshi infiltrators are coming from West Bengal to Pakur and Sahibganj—the districts adjacent to Bengal—but there is no data,” he says.

The history of the Adivasi and Muslim relationship is almost 800 years old, writes former Bihar Governor R.R. Diwakar in Bihar Through the Ages. They mixed with the early tribal residents and, as per Father Hoffman, a German Jesuit Linguist, borrowed and amalgamated of different Arabian and Persian words in the Munda dialects.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This election will be a direct fight between the JMM and the BJP on Adivasi identity, and the issue of infiltration. Which party’s narrative the voters buy will determine the outcome.

(This appeared in the print as 'Who are we? Who is them?)