There is something about the collective sigh of relief that the Indian centrists and liberals are heaving about the results of the Indian general election that does not entirely sit well. The results are, of course, a welcome reply to TEN years of Indian democracy with “Modi-fied” characteristics (pun intended), but one would also have to think very carefully about the kind of Opposition that is coming into play, and the histories and present-day practices of those political parties. The dynastic tendencies within the Indian National Congress for example; or the authoritarianism of a leader like Mamata Banerjee. In the exhilaration of a renewed Opposition led by the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), amnesia regarding the questionable record of key parties within this formation ought not to be overlooked. Nor, for that matter, should the past hamper the future potential of this novel political experiment. This is not to say that there is no reason for hope but to invite recognition of just how early are the days of not merely cutting the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) down to size, but eliminating their ideological agenda from Indian society itself and crafting in its place an alternative vision for the future of the country.

To my mind, the present conjuncture extends a potential opportunity to push the centre of gravity of India’s political universe further to the Left than it has been for many decades. Once the culture wars are won (and they inevitably will be), and Hindutva exhausts itself, politicians will have to confront the fundamental societal issues before the government of India. And then, the old questions of the nature of socio-economic development will have to assume priority; front and centre.

Last October, India ranked 111/125 in the Global Hunger Index. Unemployment is at 8.1 per cent. Inflation is 4.83 per cent. The top 10 per cent of the Indian population holds 77 per cent of the total national wealth. Seventy-three per cent of the wealth generated in 2017 went to the richest one per cent, while 670 million Indians―who comprise the poorest half of the population―saw only a one per cent increase in their wealth. Income inequality is clearly through the roof. I would like to know what the rejuvenated opposition will do to materialise the kinds of social justice required to transform these ghastly statistics (which, indeed, are but the tip of the proverbial iceberg). Business as usual, must not, and cannot, continue.

The traditional Left parties performed, but marginally better over their previous campaigns for seats in the Lok Sabha, even as they fielded the fewest number of candidates in their electoral history. This time around, the CPI(M)―Communist Party of India (Marxist)―won four seats; in Tamil Nadu (2), Kerala (1) and Rajasthan (1), up from three in 2019, while the Communist Party of India (CPI) has won two seats, the same as last time, in Tamil Nadu. The Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation (CPI(ML)L) won two seats in Bihar. Moreover, the election of Amra Ram in Sikar, Rajasthan, over the BJP’s incumbent candidate―points to possibilities of future contests between the Right and Left in particular. Again, while slender in consequence at the moment, another notable observation of how the Left-leaning voters mobilised comes from West Bengal. West Bengal, certainly was a, if not the, historical stronghold of the Communists for the three last decades; they have seen their numbers dwindle ever since Singur and Nandigram in 2011. This time around, they were unable to secure a single seat in that state. Nonetheless, significantly, the younger among the CPI(M) candidates drove enthusiastic electoral bids, increasing the party’s vote share. The popularity of the Left with students, for instance, remains a source of potential electoral gain, if combined with the appropriate strategies and grassroot tactics.

Of course, it may be argued―and the contention would conceivably ring true―that the Left in India comprises a far broader umbrella of political parties than the Communist parties alone. A number of examples will illustrate this observation. Most obviously, one would have to consider certain trends within the Congress party, and its gradual drift―for reasons too complex to go into here―toward left-of-centre policy prescriptions and ideological tenor in the recent past. The party has made concerted efforts to diversify its representatives. The Congress’ ability to forge opposition unity in the face of the juggernaut of Hindutva with political formations like the socialist Samajwadi Party or the populist All India Trinamool Congress (the two parties with the highest number of seats in the INDIA alliance following the Congress itself), also extend possibilities that hitherto may have seemed impossible if not downright absurd.

Yet, even as these developments portend well for opposition unity, it remains an open question as to what the substantive, positive contribution of the INDIA alliance will be to the narrative and trajectory of Indian politics if it is to serve ends beyond the objective of defeating Modi’s BJP. And here, the political classes and the people of the land will have to face, and make, a choice between the kind of crony capitalism that has been pursued vigorously for several decades, or adopting socialist political economic priorities best suited to addressing the kinds of concerns the common citizen have expressed, time and time, again. This will not be an easy choice, given the Congress’ prominent role in deregulation, the opening up of Indian markets to foreign investment, privatisation and financialisation. But, if the party has learned the lessons of recent years, it would do well to heed the people’s desires, wants, and indeed, needs. It would do well to not squander the opportunity it has, by eventually ignoring the warning sounded by the Indian people and resuming its uncritical friendship with big capital. Yet here, and now, there lies a chance to collaboratively mould a new vision for a socialist India by parties, both of the traditional parliamentary Left, as well as those that have historically pursued a more centrist path. Indeed, the Congress might rediscover the socialist ideals that historically guided much of its trajectory. The net effect would have to be a radicalisation and an uninhibited swing to the Left in the coming decades.

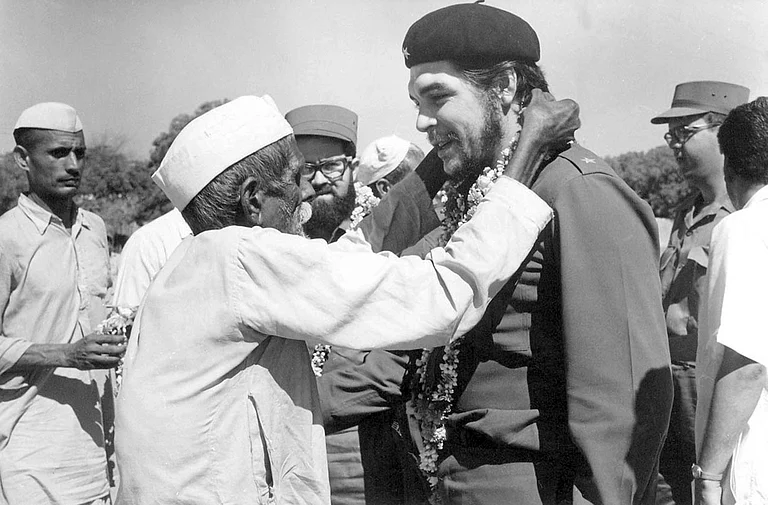

Let us address the elephant in the room: Hindutva. Soft Hindutva, of the kind demonstrated repeatedly by the Congress in past instances, is inadequate to negate its more virulent and violent expressions by the BJP. This writer is of the view that it can only be an internationally coordinated effort that can overwhelm the designs of the Hindu Rashtra, and as most historians will acknowledge, the roots of internationalism are to be found in the history of socialism. Can one imagine a Left in India that while deeply grounded in the conditions of that society equally reaches outward to cultivate alliances, solidarities, and affective bonds, with Leftist forces the world over? Can one conceive international socialism as the power that ultimately plays the critical role in provincialising Hindutva?

There are, of course, various steps that would have to be undertaken before this became a reality. The parliamentary Left, for one, must lose its own dynastic and elitist character, and enable the inclusion of representatives at the higher-most levels of people from working-class backgrounds. How much longer will the Karats and Yechurys remain the sole spokesmen? Chastened suitably, the Left might consider democratising its own party structures, function, and cadre base in order to win back the position of authority it once occupied not too many decades ago from the people themselves. Working in concert with the more centrist partners in the alliance, the Left might capitalise on―in collaboration with ideologically aligned parties, associations, and formations abroad―what may be considered a certain moral high ground with respect to the formulation of policy. For it is clear beyond reasonable doubt that neoliberal capitalism (and what is now morphing into what I consider post-liberal capitalism) has not served the lives of the working people in India the way it was intended and promised. The Left―howsoever construed―is infinitely better suited to craft policies that are more effective, efficient, and generously serve the hungry, desperate, and the astonishingly patient people of India. It will ultimately be a choice, to put the matter in the starkest terms, between Hindutva’s capitalism and international socialism.

(The author is a historian)

(Views expressed are personal)