The hypocrisy inherent in the public discourse on reservation for women in the Lok Sabha and state assemblies matches in scale the radical nature of this measure expressed in the Constitution (108th Amendment) Bill, 2008. The truth of this assertion becomes palpable if you were told that a large section of cheerleaders of women’s reservation consists of those who ignited the fire of hatred over the V.P. Singh government’s decision to implement the Mandal report, deliberately stoking it until the leaping flames consumed many an innocent soul. Once the stratagem of employing the shocking sight of self-immolations failed to prevent the implementation of Mandal, there arose a whisper demanding preference to the poorer among OBCs in the job quota reserved for them. It was then argued, shouldn’t an OBC peon’s children be given preference over those of an OBC IAS official?

This sentiment was subsequently expressed and formalised through a Supreme Court judgement ordering the exclusion of what it called the creamy layer. Through an executive order, children of certain grades of government servants or those whose parents’ annual income exceeded a certain limit were placed outside the ambit of reservation. This measure was hailed as a triumph of judicial sagacity, obviating as it did the possibility of the privileged among the OBCs cornering the benefits of reservation in perpetuity.

Yet, in an astonishing display of hypocrisy, the opponent-turned-supporters of affirmative action have shied away from extending the concept of creamy layer to women’s reservation. Is it injudicious to ask: Shouldn’t those who earn a certain prescribed annual income or belong to a family that does be debarred from contesting from constituencies reserved for women? Better still, shouldn’t this creamy layer include women whose parents and grandparents have been members of Parliament and state assemblies even once in post-Independence India?

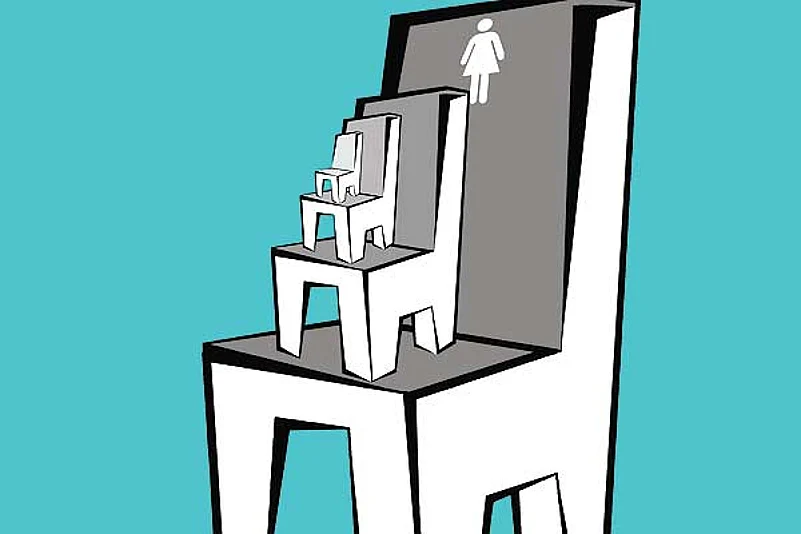

Think of the salutary effect of such a measure. It will weed out from the system, however temporarily, the political families likely to field wives/daughters/sisters from those seats they consider their fiefdoms—but now reserved for women. It will curb the role of money in elections, softening the extreme harshness of our polity. (Contrary to claims, ‘tender politics’ is rarely ever a function of gender.) Most important, it will open the political system to women from those classes which are inadequately represented in legislatures.

Privileges, social or economic, are still linked to the hierarchy of the caste system, despite the loosening of its structure. This was why reservation was devised as a tool to offset the disadvantages certain social groups had suffered that prevented them from participation in public life. But women in India are not a homogeneous group—discrimination against them is a function of both gender and class/caste. For instance, upper-class women are not only more privileged than lower-class/lower-caste women, they encounter far fewer obstacles than even lower-class/lower-caste men.

From this social reality stems the deep disquiet among certain political groups over the refusal to provide a quota for OBCs and minorities within women’s reservation. Quite speciously, it’s said that nothing prevents Mulayam or Laloo Prasad Yadav or Mayawati to field OBC women from reserved seats. But take stock of their onerous task—they must field women in 80 assembly seats in Bihar and 133 in Uttar Pradesh under the new system. Considering their parties are of relatively recent vintage, and their social bases (OBCs and minorities) still socially backward, they would be hard-pressed to find women candidates in such large numbers, bold and savvy enough for the hurly-burly of elections. They justifiably fear they will have to turn to more confident upper-caste women to make up the numbers. There aren’t just too many Phoolan Devis or Rabri Devis around. (And remember, even they were derided for being uneducated.)

In contrast, the national parties have both an upper-caste leadership and social base, besides boasting a century-old history of political mobilisation they can bank upon to field suitable women candidates. No wonder, OBC leaders fear women’s reservation will be a weapon the national parties, particularly the Congress, will wield to make deep inroads into Bihar and UP, the states to which the troika of Mayawati, Mulayam and Laloo are confined to. Any weakening of their parties in these states could sound their political death knell. This is ultimately the goal of Congress’s gender progressivism. Otherwise, it would have adopted the creamy layer concept for women’s reservation or lowered the percentage of reserved seats to build a consensus.