There is a clown, Santushta, in the Sanskrit play Avimaraka by Bhasa, circa 4th century AD. Asked if he was a Brahmin at all, he retorts: “Here, look at my sacred thread!” The sacred thread, he knew, is the supremely unimpeachable proof of elite caste identity for men. But it has other uses as well. In another, more famous Sanskrit play, the Mricchakatika of Shudraka (5th century AD), there is the clever Brahmin called Sarvilaka. He is thievish, and plots against Charudatta, the hero. Sarvilaka wants to break into Charudatta’s house. He identifies a vulnerable spot on the wall, but realises he had forgotten the measuring thread to mark out the area where he could bore a breach. It is all right, he assures himself: he can put his sacred thread to good use! For, the sacred thread is a tool of great help (mahad upakaranam) to Brahmins, especially of his kind! “One can measure a passage in the walls with it, untie the knots of ornaments, open the doors fastened by a bolt and dress the wound of insect- and serpent-bite.” He, accordingly, measures out the area on the wall with his sacred thread and bores through the wall. As he was almost finished, a snake bites his finger. He ties up the finger with his sacred thread and is promptly relieved.

Why is there so much of disdain in the thread’s description from such early times on? The sacred thread (yajnopavitam janeu), the mark of men who claim to be of “upper castes”, is worn at the time of initiation. The material prescribed for it varies from caste to caste—cotton for Brahmins, hemp for Kshatriyas and wool for Vaishyas. The age of initiation when it is first worn also varies according to the caste. In any case, it is described in a formula chanted at the time of its wearing as the “ultimate” (paramam) and “pure” (pavitram). Born simultaneously with the creator (prajapatheh sahajam), it is thought to bestow longevity and prominence as well as power and brilliance. It is a mark of respectability. A person wearing the thread has free passage everywhere; he is held in high esteem and fed with the highest respect.

While the prescriptive texts are full of praise for the thread and its wearer, descriptive texts, especially in poetry and drama, also show contempt for it and its wearer. The fact that the wearer of the thread, called poonu nool in Malayalam, is eligible for a free meal has earned it its other name, oonu nool, meaning the thread that guarantees a meal! A 17th-century Telugu play, Annadanamahanatakamu of Purushothama Dikshithudu, produced in the court of the Nayakas of Thanjavur, makes these lecherous, greedy Brahmins butts of almost scatological humour: they have nothing Brahminical about them, in the canonical sense of being learned, except their threads and tufts.

This is what happens when symbols overtake their substance. In today’s context, when the entry into a temple by the leader of a political party is defended by its spokesman because that leader is a “janeu-dhari (or thread-wearing) Hindu”, one feels sad and angry. The anger becomes all the heavier on realising that the thread is brandished as an apology for having entered the Somnath temple—and the election campaign of the party is hoped to be bolstered by worshipping there. And that party is supposed to have its claim to greatness in its championing of secularism and the eradication of caste differences.

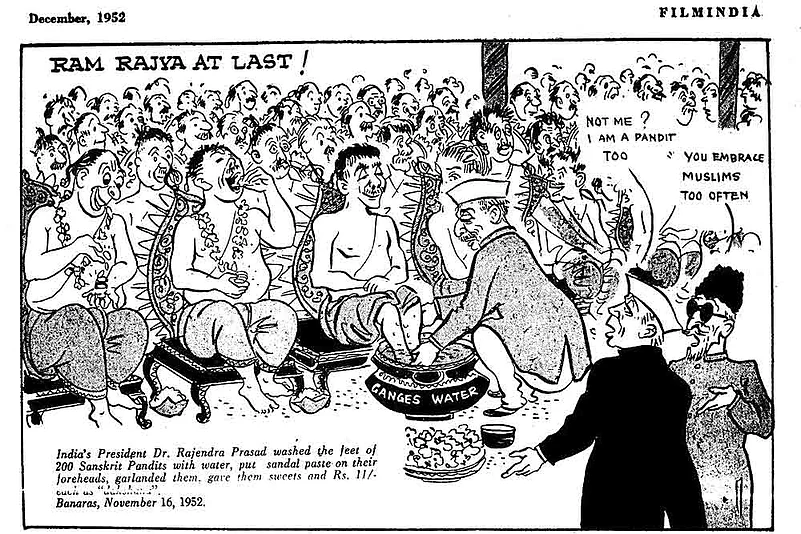

Rajendra Prasad, Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad feature in this 1952 cartoon on secularism

In 1951, when a new temple was constructed at the Somnath site, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had categorically denied the government’s association with the activity as it was “inimical to the policy of a secular government ruling a secular state”. He had also expressed his disapproval, in no uncertain terms, of the President of India presiding over the opening of the new temple. Dr Rajendra Prasad was free to visit the temple as an individual; what Panditji was objecting to was the President “participating in a significant function, which, unfortunately, has a number of implications”.

Not only did Panditji’s great-grandson, now at the helm of party affairs, visit the temple with his thread as the passport, but he also used the same temple from where the notorious rath yatra—and with it, a whole new era in Indian politics—was launched, as a platform to start an election campaign where an out-and-out communal party is the chief opponent. Thereby he forfeited any claim to the legacy of his great-grandfather. If it is the second-fiddles, more loyal than the king, who are eager to flaunt the thread that the master wears or does not wear, things are worse.

(The writer is a former Delhi University professor)