A whir greets me as I enter the sleek gallery. The hum uncanned by a push on the glass door is generated by the audio-visual presentation constantly gardening the minds of the visitors to this retrospective exhibition of photography of Shahidul Alam, curated by Ina Puri. It reminds me of a thousand voices and the movements of their hands, that of the workers, migrants, domestic helps, artists, photographers, people singing and dancing in summer, clapping once their leaders breathe after a long speech, pressing the buttons to elect them, raising their hands in rage when the promises are reneged, toppling the thrones when nothing else matters in their existence.

Forget his numerous achievements you read about, the 2018 Times Person of the Year, CASE Art Fund’s Humanitarian of the Year Award, all the works you perused in almost every magazine across the world, and rather try to perceive the purpose of the curator and the photographer at Emami Art, Kolkata Centre for Creativity. Realisation dawns that you have been one of that throng, and that your eyes have seen the beauty immortalised in Alam’s photographs.

The exhibition opens with the photograph Floating Forest. It was 1983, Alam was awarded the Harvey Harris Trophy for the ‘Best Photographer of the Year’. “I was new to photography,” says the photographer, a Doctor of Philosophy and research chemist who can invent alternative printing processes for photographs. Perhaps the swans in Alam’s 1983 work, although amorous and innocent, play an oboe in my heart the first time I see them. The Sinewy Snake (1982) makes me shiver as if I identify the skeletal creature with my ever-bending spine. Someday, it may hiss from the id. The photograph itself is crisp and exposes its technical splendour.

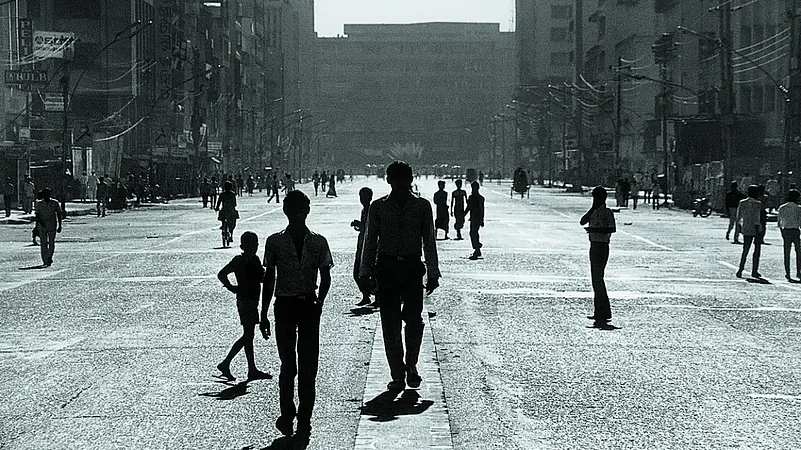

Alam has marched with the time that morphed him into a stark observer of social inequalities, and made him reflect on the fight to even out the same. The fighters of social justice would sit with their hands folded; patience bitten like their nails. The statues would stand tall above them. The frame would let your eyes travel to the end of the roads, not quite the closings, but in sooth, the infinity.

Alam tells me about Raindrops on Drik Terrace (1993), captured after his return to Bangladesh. The raindrops turned into a fistful of black pearls on the terrace of the country. “My photography was changing and the early pictorialism was making way for more documentary practice. I liked the red oxide floors of old, but the craftsmen who made them were gone. So, we built a lathe and made our own tiles and laid them on the Drik Terrace. And then the raindrops came.”

Then there is Onno Chokhe Dekha (1992, Seeing with Another Eye). Alam had established Drik Picture Library to magnify the voice of the local storytellers, but there were few women and almost next to none from the working class in the Bangladeshi media. A few friends and Alam set up Onno Chokhe Dekha, the first women photographers’ collective.

I remember the short story, Kototuku Kshoti (The Quantum of Loss) by Subodh Ghosh where a painter competes with a photographer for supremacy and the photographer captures the harshness of the 1943 Bengal Famine without any cosmetic emotion that tore apart even his archenemy painter. A photograph is real, but a reflection of the trinity—the object or the event, photographer’s philosophy or doctrine, and his state of mind or psychology. How and why he prioritises and balances certain elements in his frame determine what his art proclaims.

The photographs, Begum Khaleda Zia before election and the one after she was elected, speak for themselves. In both frames, the leader is out of focus—in one, beyond the common people and supporters and in the other, behind the stern security guards. The photographer is the sentinel for conscience. He cannot stop the evil. He can find it and point out the anomalies.

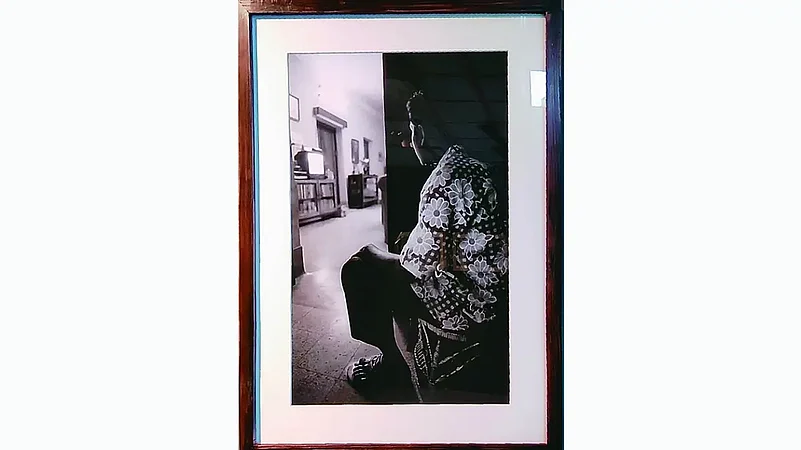

Imagine half-a-century or more from this day. Imagine the progeny studying these annals. Won’t they desire to learn more about, say, Noor Hossain and what the graffiti on the wall refer to? Mizan (1996) portrays a domestic help watching television through the space left open by an ajar door from his seat in the corridor. An outsider who helps with the chores of the insiders. The photographer says, “Mizan is a house help in my parents’ home, and used to watch TV through the open doorway in the corridor, while the family sat inside. The day after the photo was published in the Drik calendar, Mizan sat inside to watch TV. A small step in physical terms, but a giant leap in social terms. That’s when I knew my pictures could make a difference.” Art is not what you see, but what you make others see, said Edgar Degas. There lies the tool for bringing the changes.

An open letter to the prime minister of Bangladesh is displayed in the exhibition. It is not a photograph, but another weapon of democracy. Alam says, “We had expected the democratically elected government to be different. On March 26, 1992, around a million people had gathered at the historic Ramna Park to demand the trial of the war criminals. The news that day talked of big and small events and even mentioned the man of the match in a small town. It failed to mention the march of a million. The open letter to the Prime Minister reminded her that state media belonged to the people.”

Try not to visit the exhibition with preconceived notions. I cannot endorse an easy-learner’s book to figure out the puzzle of time’s pressing narrative.

Apart from Alam’s own photographs, the exhibition will present vignettes from his life and show among other rare visuals, models created by his niece Sofia Karim of the layout of Keraniganj Jail where he spent 101 days for engaging in the student protest movement. The curator, Ina Puri, says, “As committed as he is to his activism, the viewer cannot but conclude that Alam’s eye is aware of the beauty at the moment, for the aesthete in him is never too far away.”

Some of these photographs will haunt us because we know their elements, while we love the others because they show us the world we could have seen, but did not. There is Sinewy Snake (1982, clicked in UK) with all its juxtaposition and there is the face of a migrating worker leaning against the glass partition of the airport, soft, almost too mellow to be forlorn, and on the other side is his wife. The moment is so puny that it can be held inside one drop of tear. It is so big that we can travel a few light-years within it.

(This story appeared in the print edition as 'A Matrix Of Varied Realities')