Markets are a-boom—from cement to software, art to underwear—and are blithely indifferent to politics. Leaden-footed governments have ceased to much perturb the dynamic parts of the economy, and Indian capitalism’s confidence today is such that it can brush off a major terrorist attack in its own heartland and maintain its upward climb.

The new statistical India—we can all cite growth rates now, discourse on the ‘demographic dividend’, recite how many new mobile phones joined the networks last week—has combined with the sense that India is now at least a cub member of the big boys’ club, that Washington above all wants and maybe actually needs us. Even Beijing is starting to acknowledge that India’s democratic experiment has not been entirely a waste of time. And in countries that once saw the India of fly-ridden, emaciated children and dynastic, corrupt politicians, every self-respecting think-tank is hastily putting together an ‘India programme’, international journals are doing their ‘India issue’, investment banks and management consultancies their ‘India retreats’.

Of course, there are carpers and critics willing to drizzle on this happy parade: and even moderate sceptics can adduce plenty of bubble-pricking evidence. Yet there is little doubt that deep changes are under way. The horizons of possibility are broadening, in slow but cumulative ways: a new mood—not yet sharp enough to be called a new self-image—prevails. In a world where the news every day underlines the Athenian thought that "the strong will do what they can and the weak suffer what they must", India seems to be gathering itself to be on the side of the strong. What will that mean?

This is a phase of self-reformation: a point at which three fundamental questions press sharply, each of which has received different levels of attention and clarity in our recent public life. How do we think of ourselves as a community: who are we? What is our view of justice: what sort of a society do we want to be? And what is our conception of power: what do we wish to do in the world, and to prevent it from doing to us? These connected matters—of identity, of solidarity, and of security—are ones each of us as citizens will need to think through clearly, and to deliberate over with one another. For, out of our individual answers, and dependent on whether we choose to express them peacefully or violently, with conviction or diffidence, will come into being the new India’s vision of itself.

***

The question of community is the most familiar one. In recent decades, we have been embroiled in disputes over who we are, over our identity—with destructive effects. The assumption has been that we can agree on an answer to this question, that we can discover some attributes that we might all share. Various ideas of community and nationhood have been proposed. Hindutva, caste, the ‘people’ of People’s War groups, and of course many other little nationalisms. Religion, culture, language, ethnicity or blood, a common history, all have been invoked as responses to the question of defining ourselves. Yet in practice, each of these excludes fellow countrymen, and incubates resentment and aggression. Every answer set in such terms can only succeed by stipulation and imposition. We are, as Ramachandra Guha has so strikingly phrased it in his forthcoming history of our country, an ‘unnatural nation’.

Surely what is distinctive to the Indian project, what makes us who we are, is not that we have sought to live only amongst those with whom we share supposed commonalities (that, after all, was the desire for a land called Pakistan), but that we committed ourselves to living alongside those with whom we do not necessarily share much. This may be an uncomfortable fact, but it is part of the necessary business of Indian life. Today, our society is in many respects becoming increasingly diverse, and its existing diversities are increasingly activated. To think that all will subscribe to a singular definition, a common Indianness, is merely hopeful.

One instance of this growing differentiation is the way regional states have become the most credible units through which to define and pursue interests. India is undergoing what is in some respects a kind of reverse process to that of the European Union: instead of power accumulating in a bureaucratic, sclerotic Brussels, it is gradually being diffused from Delhi to regional institutions and governments (of which there will undoubtedly be more, as the large, unwieldy and ineffective lumpen-states are chiselled into smaller territories). Letting them get on with the tasks of government and development will not threaten but strengthen the Indian Union.

The hope must be that the pressures of interest will prevail over the seductions of identity. Here, a focus on the individual—his or her rights, needs, hopes—is more helpful than large claims about community, and simplified pictures of such community. In all our fussing and fighting over who we are, over whether we are one single thing or another, we have lost sight of the individual: the thousand million private universes, with their differing beliefs, affiliations and loyalties but with their common wants, that make up and undeniably are India. It is time to set to rest our worries over who we are, to put aside for a time questions of collective identity—in favour of thinking harder about what kind of society we want to be.

***

Some conception of justice, attractive in itself and workable in the real world, will need to be at the core of that society. Social justice is a complex idea, and even more complicated to put into practice. There are different social spheres and activities that require to be structured by ideas of justice, and it may not be the case that a singular conception of justice and how to achieve it is valid or applicable across all these spheres. At the voting booth, in the schoolroom, at the factory or in the fields, by the solitary neighbourhood tap, in the research lab or in the bedroom: approximating conditions of justice will require different means in different domains. Yet here too, we have chosen to simplify and to narrow the terms of debate about the idea of social justice, and what policies might best achieve it.

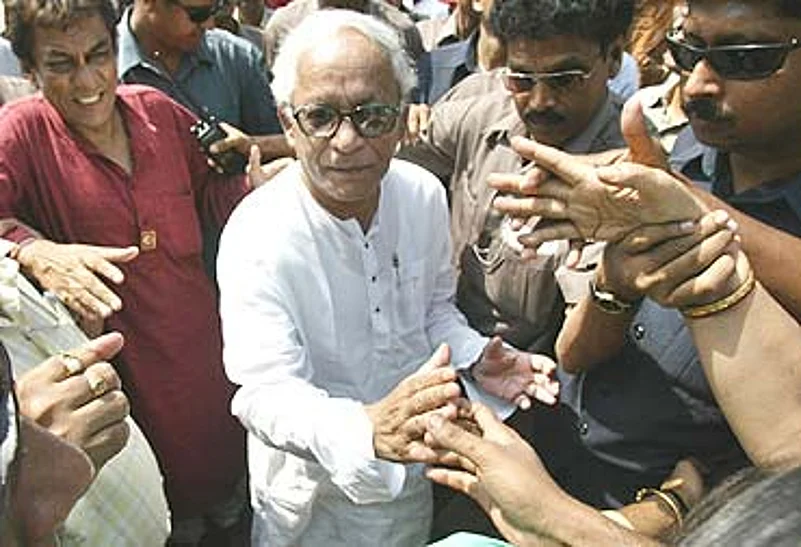

Punch & Judy: The distortive role of caste makes us all partisan

Caste undoubtedly has been the ever-turning engine of injustice in our society, blighting all social relations, corrupting the imagination, and still skewing access to markets for most Indians—though it is increasingly less able to constrain their political choices. The recognition that caste played this profoundly distortive role in society was central to India’s constitutional founders. Their judgement was that reservations were the way to correct these distortions. That historical choice—always believed to be a contingent one, whose efficacy would need close monitoring and which would in time require revision—has been transformed in the hands of our politicians into a theological, thought-deadening maxim. The politics associated with reservations have certainly improved the representational aspects of some of our democratic institutions; but how well have the goals of social justice been served? Reservations have become a cure-all, even as the evidence of their efficacy is too scarce and too disputed to justify the confidence with which positions, for and against, are taken. And so we see the whole large, complex subject of social justice reduced to ‘reservations’—and further trivialised in the Punch and Judy way this is now discussed by the political class. On the other hand, businessmen and economists ask us to put our trust equally credulously in an abstract idea of merit and in the market, to believe that growth’s benefits will slowly trickle to the parched voids of India’s social landscape. Only very recently has there been some real attempt to consider arguments, policies and evidence together. This subject will need clear, hard-headed thought—disparities such as ours, apart from their economic inefficiency, are not in the long run morally or politically sustainable.

***

We have become enamoured of the idea that we are soon to become a permanent invitee to the perpetual soirée of the ‘great powers’, and so must swiftly dust ourselves off and dress for the part. Certainly India has always sought—and has at times held—a place on the world stage: that we should play such a role is not in dispute. But we do need to deliberate over what that role should be, and how we can most effectively achieve it.

Historically, India has tended to position itself somewhere between the powerful and the powerless, the rich and the poor—and between contending ideological groups. Its primary mode of exercising autonomy in the international domain has been negative: refusing to participate in alignments, in treaties, and in markets, which it viewed as skewed in favour of the more powerful. Perhaps this was an extension into the international domain of the Gandhian strategy of boycotts and fasts, as Nehru put it in the mid-1950s: "Asian strength exists in the negative sense of resisting." Now, India faces choices as it seeks to devise a more positive conception, and exercise, of power. What conception of power might be appropriate, given the way the world looks right now?

The international system in which India seeks to position itself is marked by three features: instability and asymmetry and, directly related to these two features, the dominating presence of the United States. International structures are fluid and unsettled, with futures open-ended. The density of interaction—between economies, states, cultures, beliefs, resentments—has climbed steeply. And the desire for greater such interaction, or the perception of this as intrusive and undesirable, today can take powerful and disruptive expression.

All the world’s a stage... but India will have to be more than a mere player

Asymmetries of international power, meanwhile, will sharpen further in years to come. Take one example. In the 20th century, poor states were usually weak, and their demands could be brushed aside by the more powerful. But in coming decades, some states with very large poor populations will almost certainly become significant world powers. In differing degrees, both China and India will be relatively rich states, but will preside over still relatively poor populations—they will have high national wealth, with low per capita income. The result will be internal tensions for each, in the face of their own people, and for the international order. It will produce struggles over the world economy and the environment, over control of high technology and of finance, over access to natural resources and to intellectual property.

In the face of such persisting and deepening clashes of interest, what common language of dialogue and persuasion can there be between the contending states? These are not conflicts that will be resolvable by the deployment of conventional power—military or economic. We will need a more subtle understanding of power, one that values legitimacy too. Any resolution of today’s and tomorrow’s conflicts will require agreement over norms and rules. All states will need to find ways to structure conflicts of interests that do not break asunder the international order into interminable, paralysing conflicts.

The clearest index of the asymmetry of global power is the fact that the US is and will remain for at least the next two decades the single most weighty international actor. In decisions about the use of force, regulation of markets or operation of international institutions, what the US chooses to do will count for more than anyone else. And the US is committed to give an enduring life to its monopoly of global power. Yet this is unlikely to be stabilising in its effects—in fact, the contrary. The aspiration to monopoly, the projection of great power, will more often than not be received elsewhere with resentment, will generate resistance. And, in a world where the institutional arenas for the articulation of such resentment and disagreement have been shunned and have lost credibility, such reactions are being squeezed onto the street, into the cellars and rooms of urban lodgings, into caves in remote hillsides—with drastic consequences. The revenge of the less powerful does not usually follow counsels of prudence; but it can be brutally effective for all that.

The US is embroiled in a foreign policy disaster it is unlikely to extricate itself from without major damage (the aftermath of Iraq won’t be like that of Vietnam: in the latter case, the US was lucky: its then rivals did not exploit their advantage, and the Asian capitalist boom arrived on cue to lift up the region; there will be no equivalent capitalist expansion in West Asia, and Iran will soon have nuclear weapons). Given this and the billowing clouds of uncertainty in the regions to India’s immediate west and north, it seems at the very least imprudent to position ourselves unambiguously on one side. Our more useful role may be to try to actively bridge divides and differences.

***

Between now and say 2026, we shall certainly face the standard gamut of potential threats—internal instability, economic failures, aggressive neighbouring states: contingent threats of a kind that any major state has to prepare itself to deal with. But one sort of threat we can be entirely sure will face us all, and will confront a country of India’s scale very acutely—the effects of the historical and current patterns of use of the natural habitat.

Return of the regions: Source of strength for the Indian Union

Human beings are in trouble in all sorts of ways today, but most profoundly, they are vulnerable ecologically, a result of their past and current actions. This is the deepest insecurity that both nations and the species face. At this level, standard conceptions of power—economic prowess, military might—are at the very least as much part of the problem as they are of any solution to enhancing our security. Conventionally powerful states—states with, say, rapidly deployable coercive force—are not necessarily best designed to address this. This truth will require us to make changes in how we see ourselves, our society, the broader world—and to devise a balance, a calculus of prudence, about sustainable levels of exploitation of the natural habitat. No one knows quite how to address our ecological crisis—but it is massively evident that it can only be addressed collectively, through processes of collective inquiry, deliberation, and compromise. India began its independent life committed to such practices, and accumulated a degree of competence in this area. It would be ironic if, in emulative pursuit of an idea of power as defined by current great powers, it jettisoned the capacities which are increasingly both necessary and in scarce supply globally.

We face a paradox whose intellectual contours are imprecise, but whose sharp edge and impress are inescapable: India’s democracy and state have now, after 60 years, created the possibilities of sustaining themselves with a degree of desired prosperity. Yet, creating and sustaining this prosperity, it appears, may ultimately undermine us: by destroying the ground on which any democracy, any state, and all individuals, are fated to live. In disarming this destructive paradox, neither the market’s cunning nor democracy, reductively understood as the expression of immediate will, will be of much use. We will need to start—and keep going—a reasoned and unillusioned public argument about what kind of a society we want to be, and how that stands in relation to the natural setting in which we and our descendants have no choice but to live.

(Sunil Khilnani is the author of The Idea of India, Penguin India, 3rd edition, 2003)