S. P. Udayakumar, an anti-nuclear activist who led the protest against the Koodankulam nuclear power plant in Tamil Nadu, finds himself unable to undertake international travel due to the absence of a valid passport in his possession. Udayakumar, a prominent figure at the forefront of the grassroots resistance against the Koodankulam nuclear facility in Tamil Nadu, endured the imposition of a multitude of legal charges during the arduous struggle that unfolded between 2011 and 2013.

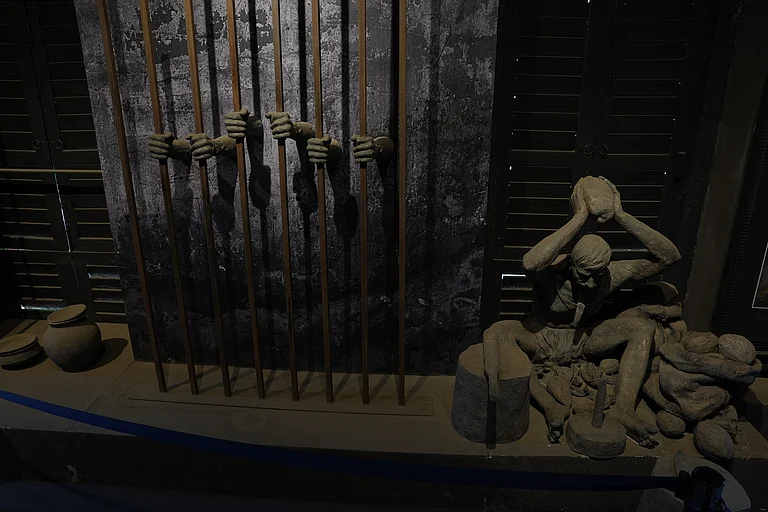

This legal onslaught was not limited to Udayakumar alone; rather, it extended to several young participants in the anti-nuclear movement, ensnaring them under a spectrum of charges, including the grave accusation of sedition. The sheer volume of criminal charges levied against the inhabitants of an entire village is nothing short of staggering.

An astonishing 2,27,000 individuals found themselves entangled in the web of 380 distinct cases. Among these, 8,956 persons faced charges of sedition under Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), the provision that has earned notoriety for its propensity to criminalize acts of dissent. Additionally, a total of 13,850 individuals were implicated under various other pertinent sections such as 121 and 121 A, which pertain to offenses akin to waging war against the State. Significantly, Udayakumar was named as the primary accused in all these legal proceedings.

In the year 2014, the Government of Tamil Nadu opted to withdraw 248 cases through a special cabinet decision; however, it is crucial to note that none of these withdrawals pertained to the charges of sedition. Subsequently, additional 32 cases were withdrawn, yet the charges of sedition remained intact.

Even a decade after the onset of these legal entanglements, thousands of individuals continue to grapple with the repercussions. As of now, Udayakumar confronts a total of 24 pending cases, including one involving the grave charge of sedition and also one of Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). In a conversation with Outlook, Udayakumar observed that the specter of sedition has been wielded as a potent instrument to stifle an entire village’s dissenting voice, one that had raised stringent opposition to the establishment of a nuclear power plant.

Individuals who engaged in protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) and the farmers protests were confronted with charges of sedition under Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), as well as similar charges under the provisions of the UAPA. According to a report carried by the research and journalism website Article 14, it has been documented that more than 3,872 individuals faced sedition charges across 26 cases related to anti-CAA protests spanning the period from 2017 to 2021 throughout India.

The debates on sedition have re-emerged following a comprehensive stay issued by the Supreme Court in May 2022, which covers Section 124A in its entirety. The Supreme Court has explicitly ruled that during the duration of this stay or until the challenged section’s legality is confirmed, no First Information Report (FIR), arrests, trials, or detentions can proceed under the aforementioned charge.

A day prior to the day of hearing, the Union government submitted an affidavit that repealing the law of sedition had been there under consideration. “The Government of India being fully cognizant of various views being expressed on the subject of sedition and also having considered the concerns of civil liberties and human rights, while committed to maintain and protect the sovereignty and integrity of this great nation, has decided to re-examine and reconsider the provisions of Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code which can be done only before the competent forum,” states the affidavit.

While the proposal to repeal sedition from the IPC appears promising on the surface, it is crucial to consider the broader legal landscape in Indian penal law. The UAPA is one such law that has raised concerns about its potential misuse to curb dissent. UAPA allows for the designation of individuals or organizations as “terrorists” without due process, leading to their arrest and detention for extended periods. Critics argue that UAPA can be used to target activists and dissenting voices, much like sedition. In recent years, there have been instances where individuals accused of sedition have also been charged under UAPA, raising questions about the effectiveness of repealing sedition if a similar provision exists in another law. This highlights the need for a comprehensive review of all laws that potentially infringe upon free speech and democratic rights.

Constitutional Conduct Group (CCG), an independent body of former civil servants, asserted that Supreme Court’s interim order of May 11, which temporarily suspends ongoing cases under Section 124A of IPC pertaining to sedition, deserves only a muted cheer. CCG emphasizes that the repeal of Section 124A alone does not guarantee the preservation of freedom of speech and expression, given the presence of numerous other analogous provisions within the legal framework including UAPA.

Furthermore, the CCG has proposed that the Union Government's willingness to reconsider this legal provision is primarily motivated by its desire to prevent Opposition-led states from utilising the sedition clause against members of the ruling party, while retaining the ability to potentially misuse the UAPA against its political adversaries.

In the statement, CCG said, “Over the years, slowly and surreptitiously, the substance of the offence of sedition has been snuck into the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 , defined more elaborately, and with more draconian consequences, than in Section 124A. Significantly, no political party is blameless in this regard and governments of all political complexions have been trampling upon human rights and the freedom of expression.”

Section 150 of Bharatiya Nyaya Samhita is reincarnation of 124A

Another complicating factor in the proposed repeal of sedition is the emergence of Section 150 within the proposed Bharatiya Nyaya Samhita (BNS).

As it stands in its current draft, Section 150 bears a close resemblance to the concept of sedition, as it criminalizes actions that could potentially disrupt the ‘unity and integrity’ of the nation. While the precise details of this provision are yet to be finalised, its mere existence raises concerns regarding whether the removal of sedition from the Indian Penal Code (IPC) will result in substantive change. Additionally, this new provision imposes a more severe penalty, increasing the potential imprisonment term from three years to seven years.

Section 150 reads; It reads, “Whoever, purposely or knowingly, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or by electronic communication or by use of financial means, or otherwise, excites or attempts to excite secession or armed rebellion or subversive activities, or encourages feelings of separatist activities or endangers sovereignty or unity and integrity of India; or indulges in or commits any such act shall be punished with imprisonment for life or with imprisonment which may extend to seven years and shall also be liable to fine.”

Advocate Balan, a legal practitioner at the High Court of Karnataka, holds the view that “this is nothing but the old wine in a new bottle”. He says that the Union Government’s assertion of repealing sedition in the name of “human rights” is merely rhetoric, particularly in light of the proposed Section 150 in the new legislation and the ongoing presence of the UAPA. According to legal experts, section 150 in the proposed law is not just a replacement of the offence of sedition under IPC, but it is worse in infringing the freedom of speech and expression.