Recently, at a queer event in New Delhi, I asked two men their pronouns. One responded “he/him” while the other said, “I don’t tell anyone. I know who I am and that’s what matters.” Earlier that day, a non-binary friend had sternly told me not to refer to them as GIRLLL in my texts.

Both reactions, different as can be, are valid ones. This is the crux of pronouns: they allow for agency.

Apart from our names, given to us sometimes before we are even born, pronouns are how people identify themselves. Using the correct pronouns is a simple way to affirm someone’s identity.

The commonly used pronouns are she/her/hers, he/him/his, and they/them/theirs. They/them/theirs are used by non-binary people who do not identify with either male or female genders. There is also the emerging ‘ze’ and ‘zer,’ another set of gender-neutral pronouns that some prefer to use instead of they/them/theirs. The practice of sharing and asking for preferred pronouns has gained widespread recognition in the last decade. The American Dialect Society’s 2019 Word of the Year vote was ‘(my) pronouns’ and the singular ‘they’ its Word of the Decade (2010-2019).

At the same event that I met the two men, I spoke to another non-binary individual who was assigned female at birth. They commended their mother for accepting that they date women but noted that when it comes to their own identity, their parents are still confused: “My mother always asks, ‘So are you a hijra?’”

My interactions with people have raised questions about the limitations of language concerning gender identity, which is intertwined with socio-economic class. Are pronouns and gender labels accessible only to the English-speaking elite? Hindi lacks distinct equivalents for ‘he,’ ‘him,’ ‘she,’ ‘her,’ ‘they,’ or ‘them.’ Instead, pronouns are integrated into the language, where assumptions about a person’s gender need to be made just to speak to them: ‘tum kahan ja rahe ho’ (for males) or ‘tum kahan ja rahi ho’ (for females).

We do have a word for transgender individuals: hijra. However, it is associated with transwomen and intersex individuals. This word has been used derogatorily for so long that it carries negative connotations. India may officially recognise hijras as the third gender, but this recognition seems limited to the legal level. It has been over a decade since the Supreme Court recognised hijras, transgender people, eunuchs, and intersex people as a “third gender” in April 2014, and yet there has been little change in societal attitudes.

The introduction of different gender identities through pronouns may understandably be viewed as imposing, especially when societal and educational reforms lag behind.

Pronouns and gender labels are becoming overwhelming for English speakers too, often excluding those with English proficiency or higher education. At the same event, I spoke to the spokesperson of a homegrown label exploring leather as a kink. When I asked him what his pronouns are and how he identifies, he said, ‘‘I have a simple rule: call me anything—he, him, chair, money—as long as there is love in it.’’

He shared that he has really struggled with a close friend. “I understand their point,” he said, “You can’t change a person overnight because for 28 years I have known them as someone. Our conversations often got stuck on pronouns.”

He mentioned a meme he saw recently that said, “What are your pronouns?” and the response was, “any/or.” Mocking pronouns with such memes and reels is commonplace on social media. One reel I came across showed someone saying, “My pronouns are USA,” with immigrants doing stereotypically American things like bulk buying, hinting at their desire to secure a green card. There’s also a section where people identify as dogs and cats.

The use of pronouns and gender labels as a point of mockery is not an emerging issue but another method for perpetuating discrimination. Throughout history, queer people were pathologised and labelled mentally ill. The decision to remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) is as recent as 1973.

In 1978, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) was founded to improve the understanding of gender identities and standardise the treatment of transsexual, transgender, and gender non-conforming people. The WPATH standards of care developed are now followed globally.

A key requirement for Genital Gender-Affirming Surgery is living in the identified gender role full-time for a minimum of 12 consecutive months, meaning a person must begin their social transition before they can physically transition.

A friend who was assigned female at birth and identifies as male underwent the process of physically transitioning to his gender. He said in his experience, using the correct pronouns for a person is about acceptance—genuine acceptance. He said, ‘‘The people who see me for who I am, using the right pronouns comes naturally. But for those who couldn’t accept it, switching pronouns was difficult.’’

In the book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Gender Identity, Judith Butler wrote, “The effect of gender is produced through the stylisation of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self.” They explained that gender identity is constituted by performing acts, and that nobody can be a gender before doing gendered acts.

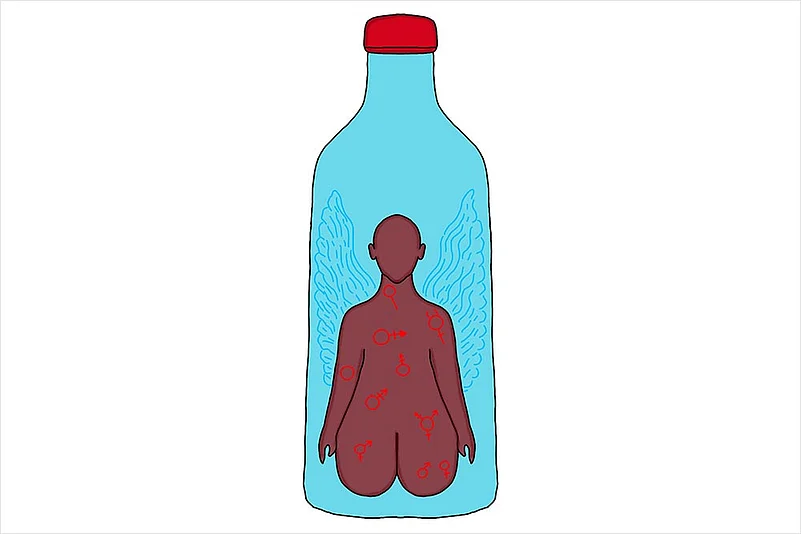

Society’s participation in individuals’ gendered acts is equally important. This participation provides space for people to perform their gender, and this is where pronouns come in. When someone tells me to use their correct pronouns, it is an invitation to participate, to provide them space to express their gender.

The sense of overwhelm that people feel regarding the pronoun question—understanding why people ask it—stems from a lack of understanding of gender identity as an abstract concept. People often directly correlate someone’s gender identity with their sex. Sex refers to biological differences between males and females (e.g., gonads, sexual organs, chromosomes, hormones). The problem lies even deeper: sex is rarely questioned and is considered a given, a law that is never challenged. According to Butler, sex is produced and established as “prediscursive,” prior to culture, a politically neutral surface on which culture acts.

Recently, in Uttar Pradesh, a man attempted to seize another man’s property by coercing him into marriage after forcing him to undergo sex reassignment surgery. Mujahid, 20, felt deceived by Omprakash, who arranged the surgery with the help of doctors from a local medical college.

This case highlights the fundamental misunderstanding of gender identity and its association with sex. The perpetrator believed that undergoing sex reassignment surgery would change his friend’s gender. However, gender identity is not determined by physical attributes; Mujahid may still identify as male, even without certain organs.

This case highlights the increasing importance of fostering environments where individuals can express their gender authentically, not only for them but also for us as a society to learn. The directness with which pronouns are asked for and shared reflects the beginning of an evolution in language and cultural norms towards understanding diverse gender identities. However, fundamental discussions about gender identity often remain confined to academia. Addressing this complex topic requires systemic changes, starting from educational institutions that should teach about self and others in more nuanced ways.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The introduction of different gender identities through pronouns may understandably be viewed as imposing, especially when societal and educational reforms lag behind. However, progress is evident, although slow. For instance, Kerala recently introduced discussions on gender roles in state textbooks, depicting fathers cooking food. Yet, society still clings to rigid gender roles. Nevertheless, the conversation has begun, a step in the right direction. With that said, I remain committed to signing off my emails as Rani Jana (She/Her).

(This appeared in the print as 'The Pronoun Question: Are We There Yet?')