It is a quirk of destiny that Rahul Gandhi never gets tired of accusing Prime Minister Narendra Modi of undermining democracy, forgetting that Modi led an underground movement in Gujarat in 1975 when Rahul’s grandmother, Indira Gandhi, imposed Emergency and suspended all civil rights and jailed thousands of political leaders. Perhaps Rahul Gandhi does not know what Indira Gandhi did to Indian democracy.

A large percentage of Indians who are below the age of 65 may not have witnessed the midnight knock that had doused the flame of democracy in India 49 years ago. That was the most draconian step taken by any prime minister who was shown to the office by the Constitution. Reputed constitutional expert of that time, Nani Palkhivala, had then said that the Indian Constitution was defeated, distorted and derailed. This was the night when dozens of editors were jailed under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA). Hundreds of leading Indian politicians were woken up at midnight and taken to unknown destinations to jail them, denying all democratic rights the Constitution had provided. This was the night when censor agents appeared in every editorial office of newspapers, weeklies and other publications, and editors were asked to remove their editorials and rewrite new ones praising the Emergency. Many editors, who refused to obey, left their editorials blank, as it happened with The Indian Express, The Statesman and many other regional language dailies.

The MISA was so undemocratic and inhuman that the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) leader, Lalu Prasad Yadav, who too was arrested the same night, named his daughter, Misa, born during the Emergency. The parties that mainly faced the brunt were the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the Congress (O), the Socialist Party, the Lok Dal, the Akalis, and to some extent the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPM). The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was banned and many of its top leaders were taken to different jails all across the country. The most atrocious aspect of the Emergency was the censorship of the press, suspension of civil rights and the total ban on political activities. Even the courts were not spared—four Supreme Court judges were superseded.

With the suspension of all democratic rights, the resistance to the Emergency went underground. Thousands of political leaders and their workers went into hiding and started the resistance movement. They printed literature, cyclostyled statements and hundreds of underground publications sprouted overnight. These underground publications were named Kurukshetra, Shanknath, Sangharsh, Prathirodh, etc.

With the suspension of all democratic rights, the resistance to emergency went underground. The underground movement was a coalition of all political parties opposed to the emergency.

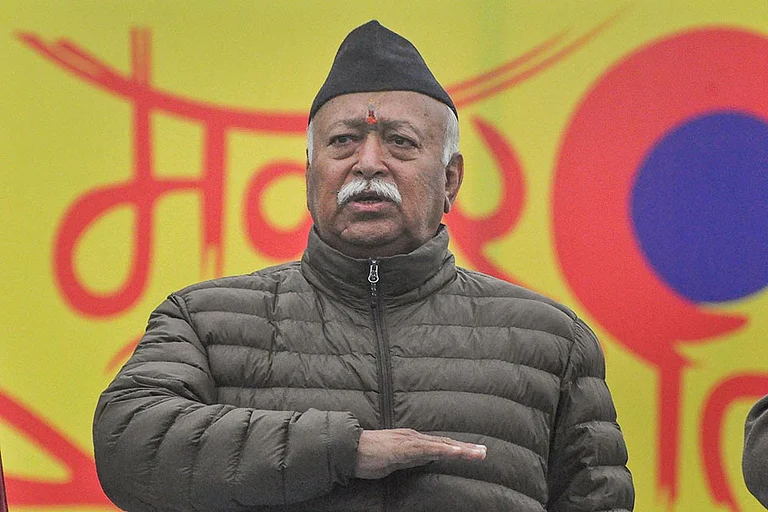

The underground movement was a coalition of all political parties opposed to the Emergency. Their goal was restoration of democracy. All the underground politicians were getting their directions from a central team. They worked in disguise, changing their routine appearance by adopting a new style of dressing, growing beards, sporting moustaches, and some like Subramanian Swamy, wearing a Sikh attire. The heroes of the underground movement were many RSS pracharaks and functionaries. Initially, the all-India coordination of the underground movement was in the hands of Jan Sangh leader Ravindra Varma. Later, when they were also arrested, senior RSS leader and Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) founder Dattopant Thengadi became the national convenor for the underground work. He had totally changed his appearance and was never caught during the Emergency. The leaders who used to wear dhoti, kurta or pyjamas began to wear bell-bottom jeans and t-shirts.

The main task of the underground movement was preparation of pamphlets, notices, statements, weekly bulletins and monthly journals. These publications carried statements from leaders who were in jails, their articles, reportage about the leaders’ life in jails, reports about protest demonstrations in India and abroad, reactions from leaders from abroad, stories about police brutality on political workers and protestors, and cartoons expressing Emergency excesses. This had become a very powerful parallel medium for information, and millions of copies in all Indian languages were printed or cyclostyled at different secret destinations. The distribution of these materials was the main task of underground activities. Through this literature, the people got instructions and guidance on how to sabotage and protest the Emergency. Most of these activities were peaceful and democratic. But there were exceptions, like the Baroda dynamite conspiracy, led by socialist leader George Fernandes.

The only Opposition-ruled state during those times was Gujarat under Babubhai Patel, and it became the safest heaven for all underground activities. In Gujarat, the convenor of the underground movement was the 25-year-old RSS pracharak Modi, who too moved around in disguise escaping arrest throughout the Emergency period. Gujarat had become the springboard of the resistance movement, and most of the underground literature was prepared and printed there. In other states, cyclostyling machines and printing presses were often raided and confiscated by the police. The people who prepared or distributed the underground literature were also arrested and jailed.

It was an uncertain future. Nobody knew when the Emergency would come to an end. Thousands of families whose lone breadwinners were in jail or many activists who lost their jobs because of their political affiliation faced disruption of their children’s education, scarcity and starvation in many cases. It was part of the underground network to collect funds and make a list of families in dire need.

There were thousands of Samaritans who secretly and silently supported the movement. They helped the underground activists by providing them food, funds and even clothes and shelter. It was because of their support that the movement could be sustained for all the 19 months. Nobody expected Indira Gandhi would announce elections in early 1977, as she had extended the life of Parliament and many state assemblies by one or two years. Even the Supreme Court had said the rights to life, property and free speech were suspended because of the Emergency. What the people got was only official propaganda. All channels of communication like radio and postal services were in the hands of the government. The infamous information minister at that time was V C Shukla, who was known for his high-handedness. In his book, All the Prime Minister’s Men, veteran journalist Janardan Thakur had listed the notorious activities of Indira Gandhi’s political aides.

Censor agents appeared in every media office and editors were asked to rewrite their editorials. Many editors refused to obey and left their editorial page blank.

The Emergency may not have ended but for two reasons: Indira Gandhi’s desire to legitimise her anti-democratic action, and the massive resistance both on the streets and in the intellectual domain organised by the RSS and its affiliate organisations. At the forefront of the ‘Sangharsh Samiti’, which was the resistance movement, were organisations and individuals associated with the RSS. Funds to sponsor the agitation were also raised by the RSS cadre. Though the organisation was banned, its entire machinery was active underground. There were civil rights organisations such as the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) of V M Tarkunde and the student’s wing of the Sangh, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), and labour organisations like the BMS that formed the backbone of the resistance movement. True, leaders of other Opposition parties were also jailed, but their cadre was not very active on the streets, fearing police repression. In the end, the resistance movement was essentially a product of the Sangh Parivar.

It must be noted that many organisations were totally confused and some even signed an apology and came out of jail on parole. It was a precondition that everybody had to support the 20-point programme announced by Indira Gandhi. Unspeakable atrocities were committed by the youth wing of the Congress, under Sanjay Gandhi, which were reminiscent of the Nazi brutality in Germany. People were picked up from the streets, offices, homes and workplaces and forcefully sterilised in the name of family planning. Localities were demolished such as in Turkman Gate in Delhi in the name of beautification. In fact, Sanjay Gandhi’s forced sterilisation campaign became a huge issue in the 1977 elections.

The process of forming the Janata Party was also initiated from jails during the Emergency. Political parties, which had come under the umbrella of a Nava Nirman Movement of Jayaprakash Narayan, came to a conclusion to form a new political outfit for sheer survival. The underground activities carried messages—exchanging ideas between leaders—which was coordinated from outside by Thengadi and RSS Sarkaryavah Madhavrao Mule. These included a series of letters from Congress (O) leader Morarji Desai, Babubhai Patel, Ravindra Varma, socialist leaders N G Gore, Madhu Limaye, Madhu Dandavate, Swatantra Party leaders Piloo Mody, Maharani Gayatri Devi and Lok Dal leaders Chaudhary Charan Singh. Jana Sangh leaders such as A B Vajpayee, L K Advani, Jagannathrao Joshi, Nanaji Deshmukh and RSS’ Sarsanghchalak Balasaheb Deoras were active in exchanging their ideas through these letters, which were written from jails, and this led to the formation of a new party by merging the Jan Sangh, the Congress (O), the Lok Dal and the Socialist Party. However, when the elections were ultimately declared, taking everybody by surprise, many leaders were of the opinion that the election should be boycotted. Leaders like Fernandes argued that with the Emergency not being withdrawn, the election would prove to be a farce, and political parties would not get a fair chance to democratically fight the election. But senior leaders of the Congress (O), the Jana Sangh and the Lok Dal argued in favour of contesting the polls.

Modi played a role in the underground liaison with the leaders and the exchange of their views. He was an excellent writer in Gujarati, Hindi, English and Marathi. After the Emergency was lifted, the RSS had a plan to undertake major research on the Emergency, explaining the role played by the swayamsevaks from underground in fighting the draconian dictatorship.

Underground literature from across the world was collected at the Sangh’s headquarters in Delhi’s Keshav Kunj, and stacked in a basement hall. The primary work of collecting and classifying the data was assigned to me.

Writing the source book on the Emergency was a major project of the Sangh taken up in 1977. Modi, who had already written a book in Gujarati explaining the fight against the Emergency, was also directed to join the task by Bapu Rao Moghe, the then all-India Boudhik (intellectual) Pramukh of the RSS. We together started the work from the RSS Karyalaya in Jhandewalan. Modi, who had great knowledge of the work and experience as one of the leaders of the movement, was able to finish this within two months. But I continued research on the subject, reading all the books published on the Emergency and collecting materials relevant for the project for another two years.

The project was abandoned after the fall of the Morarji Desai government and a split in the Janata Party. The Sangh leadership felt that the secret of fighting the Emergency need not be made public as there still existed the danger of a repeat of the dark days by the Congress to sustain its family rule.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

R Balashankar is former national convener, intellectual cell, BJP, and former editor of Organiser, presently member of all India training department and publications of BJP

(This appeared in the print as 'Notes from the Underground')