Sometime around 2002-2003, I planned to create a popular anthem for Mumbai city. The idea was to let all Mumbaikars have a song that would bring them closer to each other, irrespective of their language, caste or religion. Renowned lyricist Javed Akhtar penned a lovely song. Uddhav Thackeray was very impressed, but wanted it cleared by his father, Balasaheb, before going ahead. I was assigned that difficult job. Balasaheb listened to the song and immediately rejected it. He said the song was so good that after hearing it, more migrants would come to Mumbai. The project was shelved immediately. Balasaheb never really liked the influx of migrants into Mumbai.

When the Shiv Sena was founded in 1966, its main slogan was Aamchi Mumbai, literally meaning ‘Our Mumbai’. There were two reasons behind the coining of this slogan. One was to attract native Marathi-speakers into the party fold. The other reason was to tap into the huge resentment among Mumbai’s natives against the migrants.

The slogan had another relevance. In 1960, on the basis of the recommendations of the second State Reorganisation Commission, Mumbai Province was divided into two states, Maharashtra and Gujarat. The fate of Mumbai was left hanging. Gujaratis laid claim to Mumbai. Morarji Desai, a Gujarati himself, was the last chief minister of the Mumbai Province. Marathi leaders cut across political, social and literary lines to unitedly fight tooth and nail to claim ownership over Mumbai and other Marathi-speaking areas. It became a huge public movement. Shiv Sena founder Balasaheb’s father Prabodhankar Thackeray was one of its leaders.

Eventually, they won and Mumbai became the capital of the newly-created Maratha state, Maharashtra. Ever since, a sense of insecurity prevailed among Mumbai’s Marathi-speaking people. They held a grudge against the city’s Gujarati-speaking residents. This grudge gradually manifested into a dislike against all non-Marathi speakers. The Sena exploited this prevailing sentiment.

The party’s next slogan Uthao Lungi Bajao Pungi led to a violent campaign against the significant population of South Indian migrants in Mumbai. They occupied a majority of the white-collared jobs in government and non-government sectors. Balasaheb highlighted this reality by publicly revealing a list of positions occupied by South Indians in Mantralaya.

After that, the Sena fought a long battle to provide jobs to Marathi-speaking people in service, trade and industrial sectors. These battles were mostly violent but the Shiv Sena had its way. As the Sena grew stronger, Marathi-speaking job-seekers were picked on priority in every sector. During that period, barring the textile market, the stock, film, metal and chemical-based markets were witnessing tremendous growth. But like the textile mills, the new, growing markets too were primarily controlled by non-natives.

Raj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand ruled the film market. Rajesh Khanna, Dharmendra, Jeetendra and Amitabh Bachchan were emerging as new rulers of Hindi cinema rooted in Mumbai. Tata, Birla, Godrej and many more Gujarati, Parsi business houses had become the biggest job providers. Dhirubhai Ambani was almost knocking at Mumbai’s doors. Eventually, he provided one lakh jobs in his fastest growing corporate conglomerate, Reliance Industries. Interestingly, all these non-Marathi market rulers were on very good terms with Balasaheb. But the speed of job creation in these markets outpaced Marathi job-seekers and was resultantly exploited by North Indian migrants post-1980. Milkmen and taxi drivers had already arrived between 1950-60. But the major influx started in the 1990s.

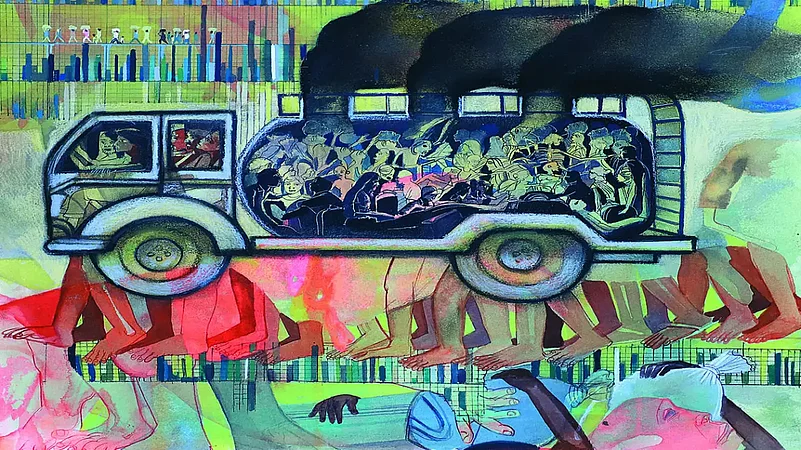

In the 1960s, Mumbai’s population was five to six million, of which the Marathi-speaking population was around 46 per cent. But over the years, migrants have outnumbered the Marathi-speaking population. Now, Mumbai’s population is over 20 million. But the percentage of Marathi-speakers has dropped to approximately 26 per cent of the total population. It is not that the Marathi-speaking population has dipped. It is just that the population of migrants has increased tremendously. And it all happened when the Shiv Sena was a major political and social force in Aamchi Mumbai. Today, North Indian migrants provide 48 essential services. Mumbai can’t wake up and go about its day without migrants’ help.

I shifted to Mumbai in 1988, not as a labourer but as a trained journalist. At that time, L.K. Advani was at the helm of the BJP’s affairs. His Ram Mandir movement, aided by RSS-affiliated organisations, was gathering national momentum. In contrast, the Shiv Sena’s footprint was limited to Mumbai. It was struggling to expand its wings to the rest of Maharashtra. Advani influenced Balasaheb to join his party’s Hindutva ideology. It clicked. The Sena contested the 1988 bye-election in the Vile Parle assembly seat on the Hindutva issue and won. It was a successful experiment of the Sena’s brand of Hindutva.

In 1989, Balasaheb announced in Pune that Hindutva ideology was the Sena’s future. The Shiv Sena and the BJP subsequently resolved to contest future elections together. Frankly, the charismatic Balasaheb was not a Hindutva follower at all. His core value was ‘Mumbai for Marathis’ only. He believed that till the end. As far as political ideology is concerned, he always claimed to be a socialist, a ‘practical socialist’ to be precise. His father was also a socialist by thought and heart. But very intelligently, to expand his party base, Balasaheb hopped onto the chalti gaadi of Hindutva. It paid him unexpected political dividends.

In January 1993, the Shiv Sena approached me to launch the Hindi edition of Saamana. I wasn’t very eager initially. Later, reluctantly, I took it up. And I gave it my best. We sold more than one lakh copies daily. The idea behind launching the Hindi Saamana was to connect with Mumbai’s migrant population. It worked excellently and Balasaheb was impressed.

Then came 1995. The Shiv Sena and the BJP formed their government in Maharashtra. The Sena installed its first chief minister in Maharashtra. In 1996, the Sena-BJP combine won all six Lok Sabha seats in Mumbai. Later that year, Balasaheb picked me to contest a Rajya Sabha seat from Maharashtra during a bye-election and I entered politics. I used that opportunity very well in the party’s interest and started organising meetings of North Indian migrants in Mumbai. Uddhav Thackeray, who was venturing into politics, addressed those meetings. I provided him with a readymade platform to connect with migrants. He impressed the Bhojpuri-Hindi speaking audiences in my meetings.

I also got encouraged to organise Chhath puja at Juhu beach. Initially, Shiv Sena leaders underestimated me. But after a couple of years, when lakhs of people converged at Juhu beach during the puja, the Sena’s ‘only for Marathi’ ideology was threatened. Murmurings among the cadre started. In 2004, I was pitted against Sunil Dutt in the Lok Sabha election as the Shiv Sena-BJP alliance candidate. I lost narrowly, triggering a huge debate within the party. Some Sena leaders concluded that the party lost because it had started accommodating non-Marathi leaders and workers. And as a result, core Marathi voters were drifting away. I became the main target of the party’s hardcore Marathi leaders.

I was summoned by Balasaheb. He bluntly asked me to stop organising Chhath puja celebrations. I didn’t dare defy him. But when I met Uddhav Thackeray, I told him categorically in anger that I would leave the party, but not stop organising the puja. He pacified me. But a crack developed in my relationship with the Shiv Sena. The rest is history.

I believe that the Shiv Sena has been in a confused state for some decades. Its core vote is off course and relying solely on Marathi-speaking people has limitations. Balasaheb had identified that limitation. That’s why he adopted the Hindutva ideology as a political ploy to expand his base in Maharashtra.

The recent rebellion by party MLAs against the current Shiv Sena dispensation has nothing to do with Hindutva. It’s just propaganda to join hands with the BJP to grab power. Uddhav Thackeray walked into a trap in his last cabinet meeting when he tried to assert his Hindutva commitment by renaming Aurangabad city. That angered both his allies, the Congress and the NCP, who have lost faith in him. His MLAs and MPs have also deserted him. It is difficult to gauge how much support he really enjoys among the cadre. But it may well be the beginning of the end of Balasaheb’s Shiv Sena.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Sainik’s Last Stand")

(Views expressed are personal)

Sanjay Nirupam is a Congress leader. He was two-time Rajya Sabha and one-time Lok Sabha member.