Lamentation has finally given way to stock-taking. On September 29, 23 people lost their lives in a stampede at Elphinstone Road railway station in Mumbai. Happening in the backdrop of a spate of train accidents across the country, the stampede turned the spotlight on Mumbai’s suburban train network, whose history coincides with that of the Indian Railways. India’s first train from Thane to Bori Bunder in 1853 ran on what would become the Central line of Mumbai’s railway grid. And it was in 1867 that the first train ran on the Western line, from Virar to Back Bay. Much has changed since and yet so little. In 1892, when the first fast local started from Bandra to Back Bay, a station between the present-day Marine Lines and Churchgate, the journey took five minutes less than it does today. This is symbolic of how little the suburban network has travelled since it was established.

Even a cursory look at the services and stations indicates there is little to show in terms of macro, qualitative and substantive development with far-reaching impact—nothing beyond extensions to the network created in the 19th century in British India. “The British left us with 40,000 km of railway tracks across the country and we have only added another 10,000-20,000 km in all these years,” says Rajiv Singhal of the Zonal Railway Users Consultative Committee. “Growth in population and increase in use of the railway network has put tremendous pressure on existing lines. It gets worse in Mumbai. Forty years ago, you lived in one house with four or five people. Now 40-50 people live in the same house. Won’t you have to upgrade the kitchen and the facilities? For the past 50 years, we are running on the same old infrastructure.” Most of the tracks were laid or planned before Independence.

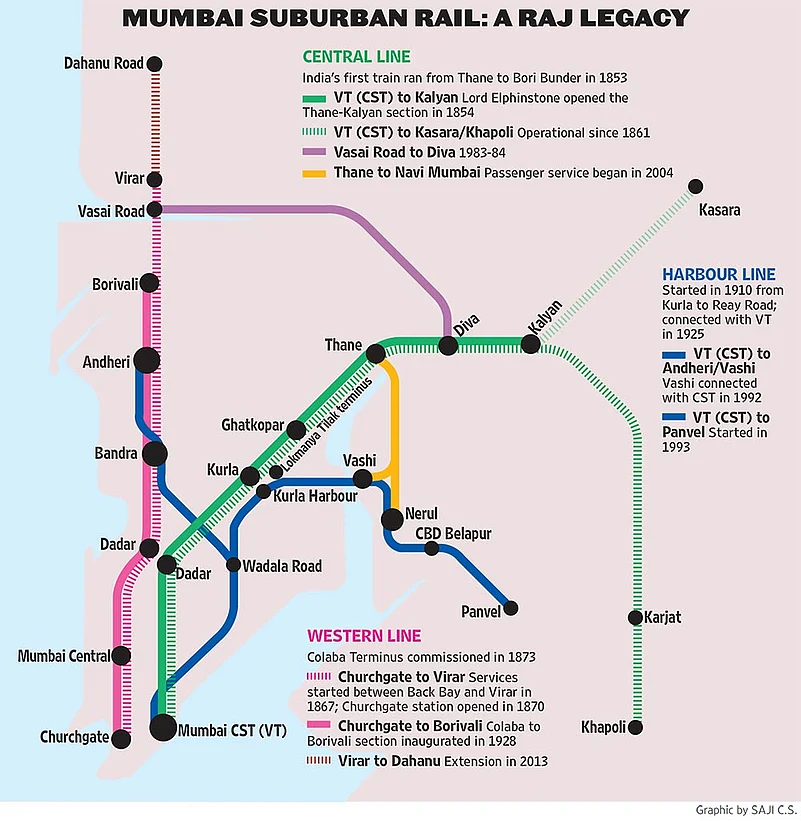

Until 1925, the trains were run on steam. During this period, the British laid tracks from Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, or CST) to Pune (which goes through Kalyan-Karjat-Lonavala) and suburban services were offered till Kalyan. The Kasara line was operational from 1861 and the Harbour line services started in 1910 from Kurla to Reay Road. On the Western line, services started from Back Bay to Virar in 1867 and Churchgate station opened in 1870. In 1925, when EMU (electric multiple unit) trains were introduced, four-car rakes ferried 2.2 lakh people on 150 services daily on the Central line. By 2001, the Central Railway was ferrying 28.5 lakh commuters and the Western Railway 29.5 lakh.

And yet, in 1971, only six lakh commuters were travelling in 586 services on the Central line. The shift towards a disproportionate services-to-commuter ratio seems to have happened over the next decade. Despite a sharp rise in the number of commuters, reaching 13.2 lakh in 1981, only 107 services were added on the Central line, taking the total to 703. In the same period, commuter traffic on the Western line went up from 12 lakh to 21 lakh and services from 477 to 715. By 2003, the western line crossed the 1,000 services mark.

The need for additional services and tracks had been raised as early as the 1960s. “Mumbai has been growing continuously. In 1964, the proposal for a trans-Harbour link was stopped,” says railway historian Rajendra Aklekar, author of Halt Station India: The Dramatic Tale of the Nation’s First Rail Lines. “There have been no serious attempts since then. There is no parallel mode of transport. In all these years, we have developed a total of seven different modes, including the metro and the monorail, but there is little connectivity between those modes.”

The Harbour line services were extended to Navi Mumbai—Panvel, Vashi, Nerul and Khandeshwar—in the 1990s, resulting in significant residential growth in the region. Parallel services from Vasai Road to Diva started in 1983-84. Addition of lines from Kurla to Thane, which were delayed by several years, and trans-Harbour links from Thane to Vashi, have been the only significant additions on the century-old network. On the Western line, the additional 5th and 6th line will still take two years to function partially. Central Railway officers point to a 33 per cent increase of capacity in the past three years with the addition of 15 compartment rakes. They also claim efficiency has gone up due to conversion of engines from DC to AC. In the past 10 years, new stations such as Nahur and Kopar on the Central line and Ram Mandir on the Western line have opened.

Former Central Railway general manager Subodh Jain rues that nobody has a sense of ownership towards this mammoth system. “Expansion is the job of the ministry of railways,” he says. “The problem is that nobody owns the suburban network. The ministry feels it is a liability. The deputed officials do not have regional aspirations and believe it is not their baby because, in 1986, the central government placed urban transport under the Union ministry of urban development under the Allocation of Business Rules. When we proposed elevated rail corridors, the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority also opposed it along with the ministry of railways.”

“When it comes to suburban expansion, the aspirations of the people of Mumbai and the planning bodies are going in opposite directions,” says Jain. “As new areas are developing in Ghodbunder, Panvel and Karjat, people want the suburban corridor alongside. They want the suburban corridor extended to Virar-Karjat-Panvel-Alibaug. They saw how Navi Mumbai grew when trains went up to Belapur. The way forward is the metro and the monorail.”

Bridge over the tracks at Currey Road railway station, Mumbai

Changes in the city’s work districts have, in fact, worsened the situation. For example, when offices shifted over the past 10-15 years from Nariman Point in south Mumbai—which has wide roads, regular bus services, efficient share taxi system and trains from CST and Churchgate—to Bandra Kurla Complex, the mill lands in central Mumbai (where the stampede happened) and the far western suburbs of Malad and Goregaon, the limitations of the railways in catering to these stations were exposed.

“The number of passengers has gone down over the years at Churchgate and gone up at stations near the mill lands and Andheri,” says Western Railway CPRO Ravindra Bhaker. “The maximum load is between Borivali and Virar. In two years, the height of 130 platforms (out of 135) was raised and 20 foot overbridges constructed, while 25 more are planned. The challenge is in executing the work at the required pace, which is tough.” According to Bhaker, the improvements are mostly technological, such as better signalling or straightening the turns in the tracks, which facilitates slightly faster travel.

Other measures to cope with new challenges include introducing the world’s first “ladies special” train. The move from stamped tickets to computerised printed tickets, coupons and now smart cards was also meant to ease the pressure on commuters. However, it is not only a case of too little, too late, but that the too little is also marred with problems. For example, having ticket windows only at one end of the platform, smart card machines not working, no proper announcements and little access to medical aid are some of the issues that make commuters miserable on a daily basis.

Though an elevated rail corridor, closed-door trains and interlinking of bridges have all been suggested, they have not yet been taken up with any semblance of enthusiasm. “We have not augmented the infrastructure in the city. For example, the World Bank was prepared to fund fencing to cope with the problem of trespassing, because of which many people are killed. But unless there is a network of interlinked bridges, how will fencing work?” asks Jain.

As of now, audit of crowds at small stations is under way following the stampede at Elphinstone Road station.