A primaeval copy of the Constitution of India, when it was drafted in 1949, was given to all MPs when they walked into the new Parliament on Tuesday when the special Parliament session started. The first copy did not have ‘socialist secular’ back then. The words were brought during the 42nd amendment in 1976 during the Emergency imposed by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Although it was the original copy of the Preamble, a row has erupted over the choice of giving out the original copies of the Constitution, which does not have any amendments that have been enacted over the next six decades. Why did the Centre choose to make this move while the current Constitution of India refers to that which has all the recent amendments?

Perhaps, the move cannot be seen in isolation as the term “secular” has long been debated in the past four decades, with the right-leaning claiming that these terms sanctioned “pseudo-secularism”, “vote-bank politics” and “minority appeasement”.

If secularism in the West has traditionally meant the separation of church from state, in India its history is more complicated and has involved respect for all religions, acknowledged by the state, especially minority ones.

The idea of secularism has been a bone of contention, here and globally, in the world of politics and in the arena of academia. The word secular, in its modern meaning, mostly means the separation between religion and state. However, it has historically been understood in different ways, reflecting various essences, including in India. In its earlier report, Outlook explored how secularism continues to be suspected and debated.

Further, at the core of the crisis, secularism faces in India, are a set of questions and a paradox. Which model of secularism should a deeply religious and ritualistic society adopt? Can one expect a believer to suddenly distance herself from her religion when she becomes part of the government? Is expecting a theist to have equal respect for other religions misplaced because a believer, unless highly evolved, tends to consider one’s religion superior? Outlook, in its article, Does Secularism Have A Place In Ritualistic India? delves into secularism facing threat both as an ideal and as a practice, as it gets caught between a deeply religious citizenry and a religion-driven polity.

Arguing on the debate of secularism, author S.Y. Quraishi, states that the political dominance of the Hindutva brand of right-wing nationalism since the 2014 elections has put into question the viability of the nation’s secular tradition and its commitment to diversity. Not only does this crisis disfigure the moral and socio-cultural fabric of the nation but it also undermines constitutional governance. In fact, the state’s engagement with religion can be said to have been one of the long-standing themes of conflict in India’s democratic experiment.

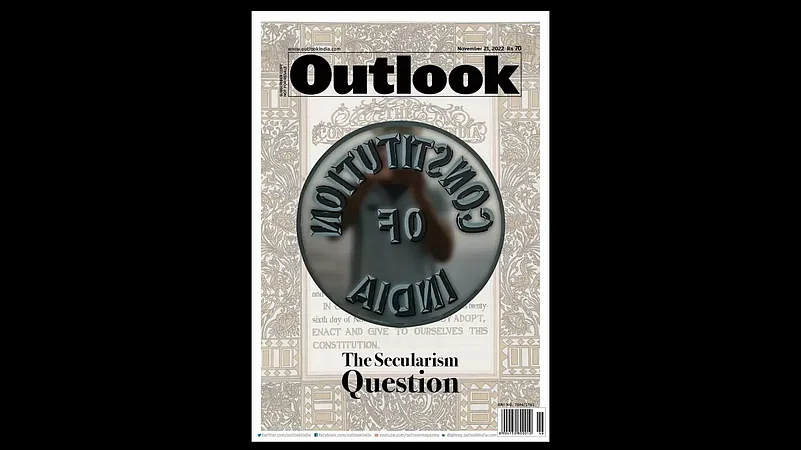

Against the rising debate of secularism, once again coming to the surface, with the onset of the special Parliament session, Outlook looks back at one of its earlier issues, The Secularism Question, dated November 21, 2022, where it tries a discourse about whether secularism in today’s India is fraying at the edges. Is it no longer a cherished ideal?