When Kashmiri author Asif Tariq Bhat started writing his novel Khwaban Khayalan Manz (In Dreams and Imagination), he thought it will not be difficult to publish it. The book was released on September 24, 2021 by a local publisher. But was a long struggle. He says it is difficult to find readership for native language authors and it is one of the reasons publishers usually refrain from publishing them.

Bhat says writers like him often carry the weight of their collective tragic political history, everyday tragedies, political upheaval and a society suffering from trauma. He is aware of it but he prefers a different theme for his debut novel.

“There are many political, social, and human issues in Kashmir. Every family holds many tragic tales. I began writing in a different genre with a purpose. My book contained a few episodes of magic realism and fantasy. To the best of my knowledge, no Kashmiri novel has traces of such sequences. I thought ‘let me give it a try’,” says Bhat.

Bhat’s novel deals with a story of a boy named Arham, an outcast in his society merely because of societal superstitions and norms. He struggles to sustain himself by working as a wage labourer. He has to keep travelling from place to place for work, as he is shunned by people of his community. Bhat says the book has been received well but publishing it was tough.

He says, “I went to a respected publishing house in Kashmir first, but they refused to publish my book, saying they don't publish Kashmiri language books. It was very sad to see this response.”

Publishers in Kashmir have no concept of editing and circulating published works of authors in a marketplace.

“Due to these obstacles, many writers have stopped writing. I got my book published as I had the resources to bring my novel into the market. This is the reason why there are few literary works published in Kashmir in the past few decades. There are no readers for our works,” laments Bhat.

As is the norm in Kashmir, Bhat’s parents insisted that he get enrolled in the medical course after completing his higher secondary Part II in 2018. But he refused and opted to study Kashmiri literature. His parents stopped talking to him for some time. Later they gave in. Bhat graduated from Amar Singh College in 2020 and later enrolled himself in the Central University of Kashmir to pursue a master's degree in Kashmiri literature.

It was in college that he started contributing to the Sangarmal newspaper, the Valley's only newspaper in the Kashmiri language, founded by the late Shujaat Bukhari — a Kashmiri journalist and the founding editor of Srinagar-based newspaper Rising Kashmir. He was also the president of Adbee Markaz Kamraz, a cultural and literary organisation in Kashmir.

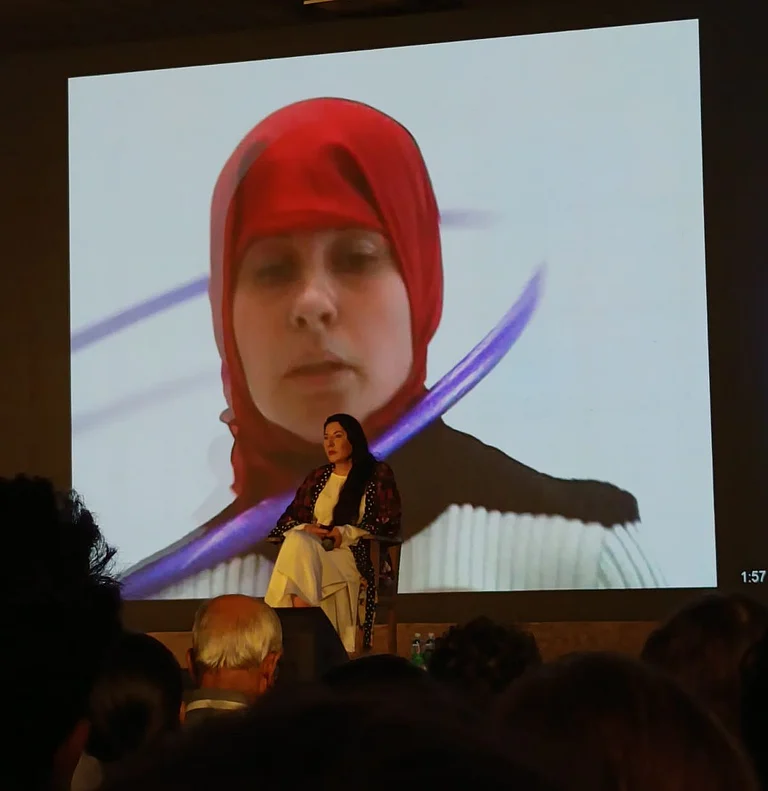

Shaista Khan’s story is different. Her collection of short stories Brande Baras Peth in the Kashmiri language won Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar this year. At present, she is teaching Kashmiri on academic arrangements in different colleges.

Khan says one needs to have a complete hold on the native language to write fiction. She started writing during her college days, but learned the craft in the Department of Kashmiri, University of Kashmir. Every Thursday, the department conducts a Kashmir literature gathering, where young writers read their poetry and prose under the supervision of their teachers.

Khan started writing short stories in 2019. With no phones, no internet, and no communication with the outside world at the time, Khan got the necessary solitude to write. She believes in portraying realism in her stories. One of them is about an old woman living in a locality in the old city of Srinagar. She lives alone and had been regular to Dastgeer Sahab, a centuries-old shrine situated in the Khanyar locality of Srinagar and one of the most revered shrines in the Valley.

On June 25, this 200-year-old Sufi shrine of Sheikh Syed Abdul Qadir Jeelani —a locally called Dastgeer Sahib— was gutted in a fire, sending shock waves across the Valley. The burning of the shrine triggered clashes between the police and angry protesters, leaving many wounded.

Khan's story says the old woman would go to the shrine regularly. When a young woman in the neighbourhood heard of the fire at the shrine, she rushed to the old woman to ensure she shouldn’t hear of it. But she found the radio in the old woman’s room repeatedly announcing the news of the gutting of the shrine, and that the old woman was dead.

With this story, Khan says, she wanted to convey deep faith and belief among the locals, especially among the elderly, for Sufi shrines across Kashmir Valley. Khan says short stories usually are based on real stories that happen in “our everyday life”.

“We observe them and we write them,” she says.

Khan’s book is very lucid and it can be read by anyone having a rudimentary knowledge of Kashmiri.

Once Khan completed her book, she got it published by local publisher Mizan. She says it is true the publishers don’t have editors but when writers write in their native language and are confident about their script, they don’t need editors. Kashmiri writers, she says, require readership, adding that the introduction of Kashmiri in all schools a few years ago has somewhat helped the language.

“Young students have started reading books on Kashmir. It is now up to the writers to write in a simpler language to reach a larger audience. If you use heavy words, it becomes difficult to reach a larger audience,” says Khan.