Born of Hari and Hara (Vishnu and Shiva), named Manikanthan for the bell hanging around his neck, raised a prince of the Pandalam royal house, banished to the forests—that’s the Ayyappan we are familiar with. But it could all be a modern fabrication, a latter-day exercise in myth-making, says an account that’s doing the rounds. Leave aside the dispute over women’s entry: in this scenario, the identity of the deity himself is in dispute. It’s a striking, contentious claim. Questions about the historical veracity of myths—as happens so often in India, from Ayodhya to Indraprastha—lead us back to a hazy maze of orality and scanty evidence, a place where historiography comes to die. Here, at least two competing myths trail off into the grey.

In the dissenting version, Ayyappan was no Hindu deity of Vedic or Puranic origin, but a hero of the Mala Arayans, a hill tribe who may have been the builders of Sabarimala temple, and were its custodians until fairly recently—perhaps. The community, now some 30,000 strong, retains ownership of over a hundred temples, and are preparing to file a petition in the Supreme Court for this and other temples to be restored to them. Who are the Mala Arayans? Literally, the kings of the hills: mala is Malayalam for ‘hill’ (as in Sabarimala), arayan comes from arachan, of distant Sanskrit origin (raja).

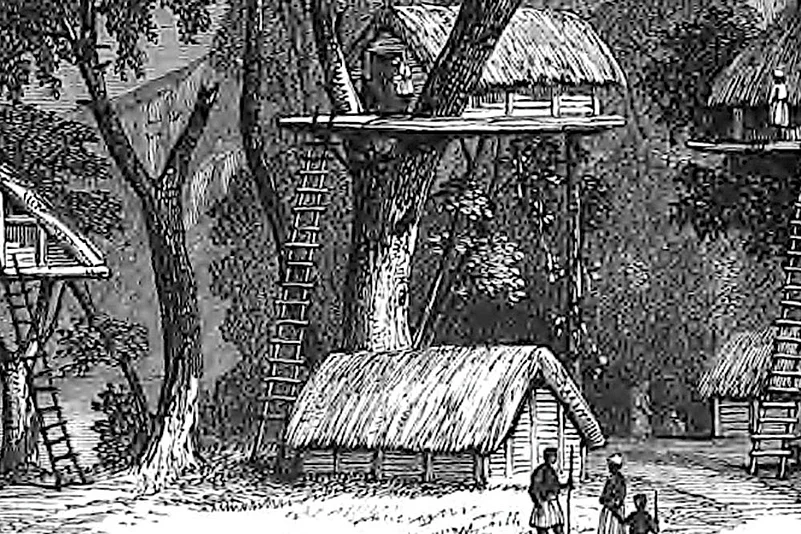

Christian missionary activity in the 19th century has furnished us with something of a portrait of the community. The Rev. Samuel Mateer, in his 1883 book Native Life in Travancore, describes them as prosperous rice cultivators living in houses scattered on steep hillsides. As for religion, Mateer says they worshipped their ancestors, or spirits resident in rocks or peaks.

In particular, Mateer narrates a Mala Arayan legend about Talanani, “a priest or oracle-revealer of the hunting deity, Ayyappan, whose chief shrine is in Savarimala [sic].... The duty of Talanani was to deck himself out...in his sword, bangles, beads. &c., and highly frenzied with excitement and strong drink, dance in a convulsively horrid fashion before his idols, and reveal in unearthly shrieks what the god had decreed...” An ecstatic, shamanic variety of religion, not quite what’s expected of today’s tantris. The story goes on: “When the pilgrims...used to go to Savarimala—a pilgrimage which is always, for fear of tigers and other wild beasts, performed in companies of forty or fifty—our hero would give out that he was not going, and yet when they reached the shrine ...there before them was the sorcerer.”

Who was this “hunting deity”? P.K. Sajeev, founder and general secretary of the Aikya Mala Araya Maha Sabha, says he was a prophesied warrior born in the early 12th century AD to fight the invaders during the “Hundred Years’ War” between the imperial Cholas on the one side, and the second Chera ‘empire’ and their southern neighbours, the Ay kingdom—supposedly the forebears of the Mala Arayans—on the other. He was named Manikandan, or ‘little Kandan’, after his father, Kandan; bell-necked Manikanthan was a plausible Sanskritism slipped in at a later date. After defeating the Cholas, Manikandan chose Sabarimala, a hill named after a hermitess of yore who’d had her ashram there, for his resting place.

Of course, that Chola-Chera war is a famously disputed story. The late P.K. Balakrishnan dismissed it as “bhaavanaavyaayaamam”, an exercise of the imagination. And eminent historians are sceptical of the Mala Arayan claim as a whole: Rajan Gurukkal tells Outlook the community had nothing to do with Sabarimala, and there has been a confusion with more local tribes such as the Ulladans, Mannans and Mala Pandarams, some of whom may have had some rights at the temple. M.G.S. Narayanan is similarly doubtful, saying this tale of Ayyappan is a “new story” he has not come across before. And yet, the Rev. Mateer begged to differ, in advance.

Sajeev says the Mala Arayans were dispossessed of their rights to the temple only in 1902, with the current Brahmin priests (the Thazhamon family) being installed by the Travancore maharaja. Practices were changed (the honey traditionally used to anoint the deity was replaced with ghee), or given Brahminical explanations: the 18 steps that lead to the temple are now related to the 18 Puranas, but they once referred to the 18 sacred hills of the tribe.

And women? Sajeev says young, menstruating Mala Arayan women traditionally didn’t go to Sabarimala—they took advantage of post-pregnancy intervals to visit. But Sajeev is not against young women devotees going now.