The idea behind Partition, and Pakistan, was that it was required to safeguard Muslims from Hindu domination. Several million Muslims migrated across the borders to East and West Pakistan; yet three times as many remained in India. The creation of a new Muslim state had not solved the problems of the Muslims who stayed behind—to the contrary, it made them more vulnerable still. Seeing this, two men who had played critical roles in the creation of Pakistan began to have desperate second thoughts. These were the Bengali Muslim Leaguer H.S. Suhrawardy and his United Provinces counterpart Chaudhary Khaliquzzaman. On September 10, 1947—less than a month after Independence and Partition—Suhrawardy wrote to Khaliquzzaman in horror that "the Muslims in the Indian Union have been left high and dry". The antagonism caused by the coming into being of Pakistan had been heightened by the flight into India of Hindu and Sikh refugees. Suhrawardy now feared that "there may be a general conflagration which can well destroy the Muslim minority in the Indian Union". To protect their interests—and their lives—he drafted "a declaration of cooperation and mutual assistance between the two Dominions", committing both to protecting their minorities and to not making provocative statements against each other. Suhrawardy got Gandhi to endorse the declaration, but failed to get Jinnah's consent, despite begging him to do so, "for the sake of the helpless and hapless Muslims of the Indian Union...."

In Khaliquzzaman's view, "the two-nation theory which we had used in the fight for Pakistan had created not only bad blood against the Muslims of the minority provinces but also an ideological wedge between them and the Hindus of India...." No sooner was Pakistan created that this key player in its making realised that "the partition of India (had) proved positively injurious to the Muslims of India, and on a long-term basis for Muslims everywhere".

Among the in-between figures of Partition there are many who are essentially tragic, and a handful who must be considered truly heroic.In the latter category falls the name of Sardar Tarlok Singh, of all the people mentioned here the only one still alive, living in quiet retirement in NewDelhi. After Partition became an accomplished fact, Tarlok Singh was placed in charge of rehabilitation in the Punjab. His job was to allot, to Hindu and Sikh refugees from West Punjab, land vacated by Muslims fleeing in the other direction. He had both the intellectual equipment (a degree from the London School of Economics) as well as the strength of character to do this quickly and do it fairly.

Working with a team of equally committed officials, Tarlok Singh made 2,50,000 allocations in two years. Very few were challenged. For the most part, the displaced peasants took charge of their new land, and set it to work. Twenty years down the line, the Punjab became the bread-basket of India. The farmers and their new technologies generally get to take the credit—in truth, at least some should be shared with the officials in charge of rehabilitating them.

Tarlok Singh and his team notwithstanding, the heroes were probably outnumbered by the heroines. Perhaps the most exemplary figures of Partition were the women social workers who laboured in riot-torn villages and gloomy refugee camps, seeking to restore communities and reunite families. Many were inspired by Gandhi, as for example Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Rameshwari Nehru, Mridula Sarabhai and Anees Kidwai. Kamaladevi directed the building of new townships, Mridula and Rameshwari directed the recovery of abducted women, Anees brought succour and hope to victimised refugees. Their life and work has been sensitively portrayed by feminist historians. One heroine who awaits a modern rediscovery is Bibi Amtus Salam, whose extraordinary fast to restore communal harmony in Noakhali is recounted in Pyarelal's 1956 book, Mahatma Gandhi: The Last Phase.

Perhaps the most intriguing woman on the other side was Mohammed Ali Jinnah's sister, Fatima. Educated as a dentist, she ran a successful clinic in Bombay in the 1920s, a feat which alone must mark her out as being most unusual for her time and place. However, on the death of Jinnah's wife Ruttie, Fatima closed her clinic and joined her brother, thereafter serving as his housekeeper, companion, and political confidant. In photographs and cinema reels of the time we see her hovering around the Qaid-e-Azam, clad always in a sari, a dress that has since regrettably gone out of fashion in Pakistan itself.

Fatima was devoted to Jinnah while he lived, and devoted to his memory thereafter, seeking to control what was said or written about him in their country as well as in the world at large. Yet she does not even rate an index entry in Ayesha Jalal's The Sole Spokesman , this a mark of how comprehensively she has been ignored by historians of Partition andPakistan.A truer indication of her importance lies in the fact that she was chosen as the combined Opposition candidate to stand against Field Marshal Ayub Khan in the Presidential elections of1965.Fatima Jinnah gave Ayub a close fight, in the end losing because the Field Marshal had more money, controlled the administration and the election machinery, and got some influential mullahs to issue fatwas to the effect that Islam did not permit of a woman serving as head of state.

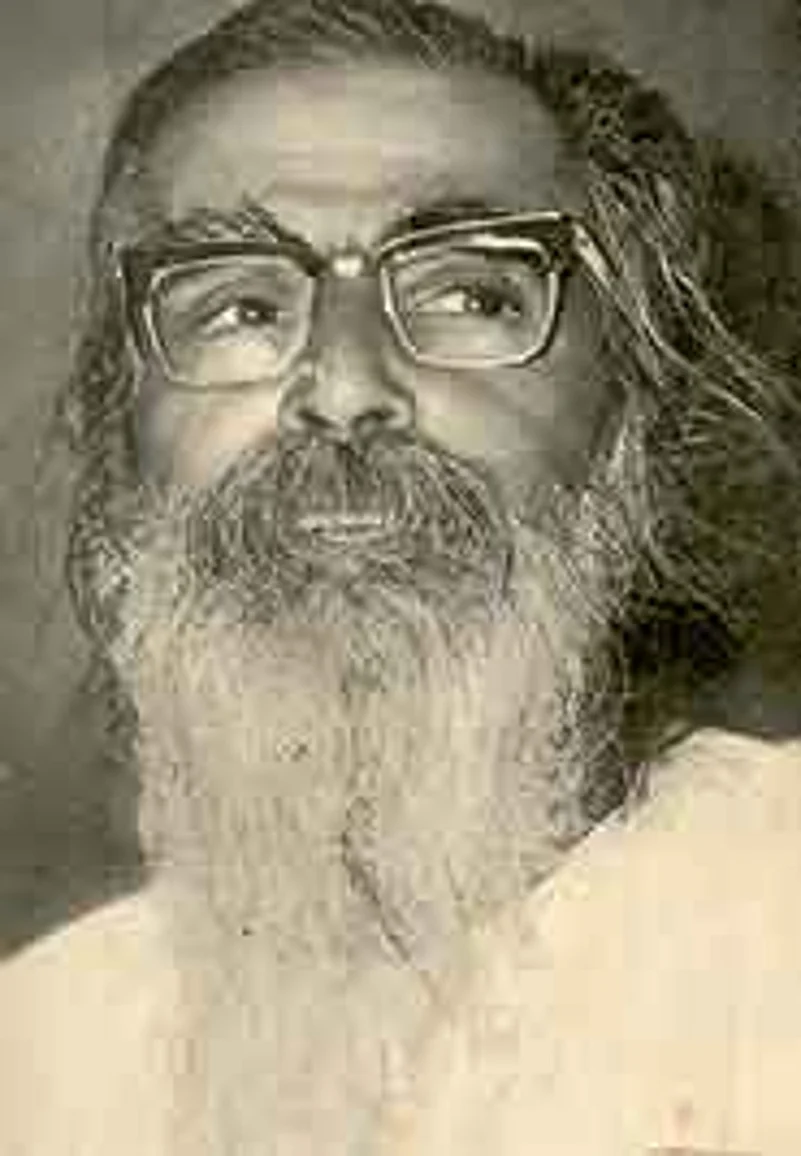

Apart from the leaders and the masses, the story of Partition thus features a whole range of middle-level figures, some of whom we may admire, others feel sorry for, and still others simply wish to know more about. There were also a few who were very nearlyvillainous. As for instance, a man named Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar.In 1947, he had served for almost a decade as sarsanghchalak of the Rashtriya SwayamsevakSangh. Bearded, with long hair and hooded eyes, originally from Maharashtra but more lately a post-graduate of the Benaras Hindu University, the RSS supremo was a man of much intelligence and motivation, this not always directed into the most productivechannels. His name peeps in and out of records I have recently been studying, which are of the Delhi Police for the autumn and winter of 1947, that is, the weeks and months immediately following Independence and Partition. These records make for very chilling reading indeed.

In August 1947, Delhi had a large Muslim population, but a wave of bloody riots had led to thousands fleeing into refugee camps. Gandhi (and Nehru) were concerned; for if the minorities were not safe in the capital, how then could India claim to be a secular state? The RSS, on the other hand, wanted to complete the process of ethnic cleansing. So said a sub-inspector of the Delhi Police named Bhagwan Das Jain. A mole inside the RSS, Jain reported on October 24 that the Sangh saw in the unsettled conditions the chance to take a bold step towards the establishment of Hindu rule in India. As he wrote, "according to the Sangh volunteers, the Muslims would quit India only when another movement for their total extermination similar to the one which was started in Delhi sometime back would take place". The RSS men, he continued, "were waiting for the departure of Mahatma Gandhi from Delhi as they believed that so long as the Mahatma is in Delhi, they would not be able to precipitate their designs into action".

By early November, Golwalkar himself was camped in Delhi, planning for future action. In a speech in Ramjas College, he noted with satisfaction that the RSS membership had increased by 2,500 in a single month. He told his audience to be prepared for the fight ahead. On December 6, Golwalkar convened a meeting of RSS workers in Govardhan, near Delhi. The police report on this meeting remarks that "the (RSS) workers are alleged to have discussed the ways and means of capturing the seats in the government.... It is also alleged that one of its (the RSS's) programme(s) would be to assassinate the leading persons of the Congress...to terrorise the public and to get their hold over them".

Millions of Indians saw Partition as a tragedy. But for M.S. Golwalkar, Partition was an opportunity, an event which, if properly taken advantage of, might increase his influence and reach manifold. On December 8, 1947, Golwalkar addressed a crowd of several thousand RSS volunteers at the Rohtak Road camp inDelhi. Also in attendance was a police inspector named Kartar Singh. His report of the sarsanghchalak's speech deserves to be quoted in extenso .The policeman reported that Golwalkar told his followers that "the time for mere playing hasgone.Our volunteers should enrol new volunteers in every house, and should instil in them the essence ofHinduism. Referring to the government, he said that law could not meet force.... The Sangh will not rest content until it had finishedPakistan. If anyone stood in our way we will have to finish them too, whether it was Nehru government or any other government.... Referring to Muslims, he said that no power on earth could keep them in Hindustan. They should have to quit this country....If they were made to stay here the responsibility would be the government's and the Hindu community would not be responsible. Mahatma Gandhi could not mislead them any longer. We have the means whereby (our) opponents could be immediately silenced".

This last sentence, when read with the last sentence of the previous paragraph, suggests that though it was one particular ex-RSS man who pulled that fateful trigger on January 30, 1948, there were other, still-serving RSS men, their sarsanghchalak included, who would have wished for those bullets to find their mark.

Periyar Opposed to north Indian domination, he spent alifetime fighting for a separate Dravidian state

There is an important book waiting to be written about the kinds of people I have touched upon here: politicians not quite as powerful as Nehru and Jinnah, colonial officials not nearly as glamorous as the viceroy, social workers nowhere near as famous as MahatmaGandhi. These are individuals whose life and work illuminates the history of Partition in new and quite unexpected ways. And our interest in them should not be wholly academic. For these are figures who, as example or warning, remain quite relevant to the practice of politics and the conduct of social life in India today. Although Partition lies 58 years in the past, its scars and wounds remain. Now, as in 1947, Indians can deal with them in one of two ways. The first is to try and heal these wounds, following the example of (among others) Tarlok Singh and Amtus Salam. The other is to make them septic, in the manner of M.S. Golwalkar and his RSS.