When leading Malayalam weekly Mathrubhumi started serializing a new novel Meesha (Moustache) by noted writer S. Hareesh in July, little was known that it would create unprecedented turn of events in Kerala’s literary world.

Just three parts of Meesha being serialized, the magazine’s editor Kamal Ram Sajeev took himself to Twitter with a startling announcement. “S. Hareesh withdraws his novel ‘Meesha’, literature is being mob lynched, darkest day in Kerala’s cultural history, lightless days to follow,” he said.

A section had alleged that a certain conversation in the novel had hurt the sentiments of Hindus. It was only some months ago that poet Kureepuzha Shreekumar was targeted and physically attacked in Kerala alleging that he had insulted Hindu gods in one of his speeches.

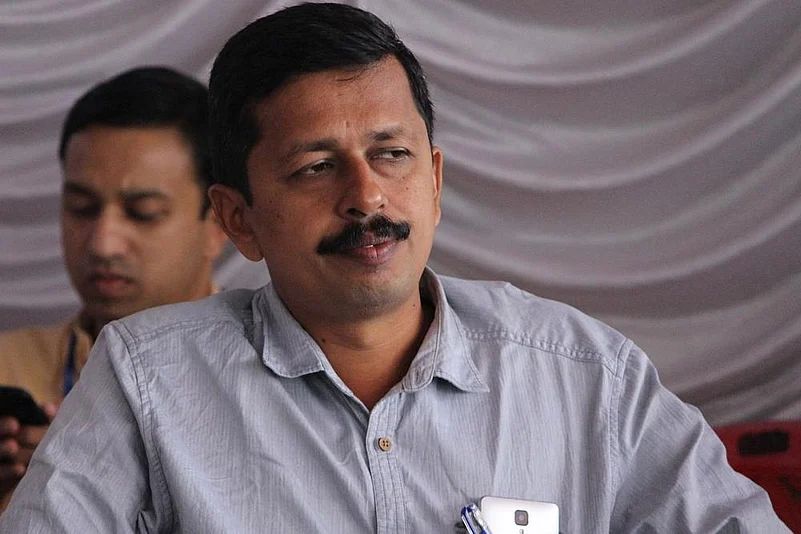

Hareesh, a Sahitya Akademi award winner, and his family started getting abuses and threats. A group reportedly vandalised an exhibition of books organised by Mathrubhumi Books in Kochi.

Hareesh, 43, who works as a village assistant, wrote to the weekly’s editor expressing his decision to withdraw the novel. “I am too weak to take on the people who rule the country. I worked on the novel for five long years,” he told Mathrubhumi TV news channel.

He was also quoted in media as saying that he would publish the novel when he feels the society is matured enough to read it.

Tamil author Perumal Murugan, who had declared that “writer Perumal Murugan has died” after threats from right wing groups in 2015, equated Hareesh with himself. “I see in him a reflection of myself. For now, I wish to hold his hand and tell him: “Time will come when hatred will subside. We shall wait,” Murugan said in an article written in The Hindu. Many writers and activists were quick to draw parallel to the growing “intolerance” towards dissent.

Hareesh offered a refreshing read in the first part of Meesha. Adopting the narrative style of folklore tales, the novel begins when a young Vavachan, the central character, travels in a boat along with his father Paviyaan.

“It is believed that eenampechi or Alunku (ant-eater) too has got some divineness like the njarappakshi and kollikkuravan (two birds) and people think that dead children sometimes come under their disguise”, read the opening sentence. The time period in the novel is mainly from 1935 to 48, and the story is based in Kuttanadu, where paddy-cultivation is carried out below the sea-level. The first part itself revealed how its characters can get immersed in the Kuttanadan environment, how they befriend the fish, birds and the stars and their encounter with the legends, folklores and the superhuman powers that are ingrained in that place.

In the second part, published in the weekly’s next issue, the time period in the novel extends to the present times and a first person story teller comes as a narrator. A small conversation between this narrator and a friend of him during a morning walk, however, became a point of contention among a section of the weekly’s readers. They cried foul over a comment by the narrator’s friend who said the women who take bath, dress up beautifully and visit temples are subconsciously declaring that they are ready for sex.“Otherwise, why don’t they come to the temple four or five days a month? They are making it known that they are not ready for it. Especially, to the Priests of the temple. In old days, they were the masters of these kinds of activities, weren’t they?” says the character. The narrator laughs to it.

A petition was filed in the Supreme Court seeking to ban the controversial excerpt. After hearing the matter, the SC said on Wednesday the culture of banning books was wrong since it affected the free flow of ideas. A three-judge bench, headed by Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dipak Misra, dismissed the petition saying 'the writer's imagination must enjoy freedom.' “Books should not be read in a fragmented manner but as a whole,” said the court, also quoting French thinker Voltaire’s statement that “I may disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it."

However, more intriguing would be to see what impact it will have on, as some critics called, "the curious mix of politics, business and literature" that was unraveled out of the Meesha row.

An influential caste group, Nair Service Society (NSS) issued a statement demanding an apology from Mathrubhumi while a prominent jewelry group, Bhima, announced withdrawal of advertisements to Mathrubhumi. “What would be the case if it were about the women from any other community?” wondered the NSS, indirectly referring to Muslim organisations forcing Mathrubhumi to apologise in 2016 for “offensive” comment on Prophet Muhammad. There were also widespread campaigns calling to unsubscribe Mathrubhumi newspaper and switch to Sangh Parivar-owned daily,Janmabhumi.

Amid rumours that Mathrubhumi management had pressurised Hareesh to withdraw the novel, its newspaper carried an editorial standing with the novel and the writer.

Meanwhile, Samakalika Malayalam Varika', a sister publication of The New Indian Express, issued a statement saying it was ready to publish Meesha. Later, DC Books published Meesha as a book registering a record sale with fifth edition going to print within one week.

“After withdrawing from Mathrubhumi, it was a case of now or never for me,” Hareesh told Outlook. In the book, a correction was made in the controversial portion. Instead of just laughing to the friend’s comments on the women, the narrator in the new version tries to ridicule him by saying, ‘Don’t be silly.’

Portraying the lives of dalits, Meesha tells the story of Vavachan, who was unwilling to shave off his moustache, which he had sported to act in a drama, even after the theatre group had left his village. During that period, sporting moustache was considered as an act of defiance. But, an undeterred Vavachan continues to sport it and earns the name, Meesha. He becomes a legend in Kuttanad.