A part of my growing up experience involved remaining in the shadows, to not invite the gaze, to not get raped.

We, who were once girls, grew up watching cinema that always mourned rapes and looked at it as the defilement of the person. The woman was then a “used” body and her honour was sacred. The honour wasn’t just hers, it also belonged to her family and her neighbourhood.

There was a film back then in 1991 called Benaam Badsha starring Juhi Chawla and Anil Kapoor. Kapoor’s character’s trajectory is to make us sympathetic towards him. He has had a sad childhood and was abandoned by his parents. He ends up raping Chawla on her wedding day and then, Chawla moves in with him to reform him.

Cinema romanticised rape by distorting it from a crime into something linked to shame and honour, shaping how we told its stories. In 2021, the then Chief Justice of India, S A Bobde, asked a man accused of rape whether he would marry the complainant.

There have been instances where rapists have proposed marriage to the women they have raped. In 2002, the Delhi High Court dismissed a rape case when the victim agreed to marry the accused. Similarly, in 2024, the Karnataka High Court granted 15-day bail to a man to marry his pregnant minor victim.

The Court emphasised that the newborn, unaware of the situation, should not face future shame. To protect the child’s well-being and support the mother’s responsibility in raising the child, the Court found it necessary to issue this directive.

There are many such stories that shock us because they stem from the belief that honour is tied to rape, denying women their agency.

The rape and murder of the junior doctor in Kolkata’s R G Kar Medical College and Hospital bring up uncomfortable questions surrounding rape. There is always the urge to find a case of mental illness or a story of trauma to say these men weren’t normal and what they did was because of a reason. We are told men who commit sexual violence often exhibit toxic masculinity and hostility towards women. In a patriarchal society, rape is rooted in power and violence, driven not by disorder, but by patriarchy itself. So far, the male gaze has been omnipresent in the media. Rape is an uncomfortable story.

The credibility of the victim is almost always on trial as much as the guilt of the accused, if not more. There is a huge gap of time in between crime and conviction and the first people to listen to the story are the police, who have to ascertain whether the victim is telling the truth.

While covering rape cases, I’ve seen how victims’ credibility and character are always questioned. We never truly listened or knew how to tell, remember, understand, or process these stories. It’s in the failure to listen where the real issues arise.

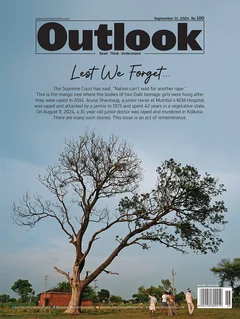

This is our attempt at a ‘Herstorical’ approach where we have tried to listen again to stories of rapes as an act of remembrance and to bring to the surface again what has been submerged. A rape isn’t an isolated case. Not for me. Not for any woman.

Read, remember and revise the stories because silence is never good. And I don’t think girls should be told to keep themselves safe all the time lest they get raped.

(This appeared in the print as 'To Speak Of The Unspeakable')