As you veer off Uttar Pradesh State Highway 709A, past sugarcane fields, stopping in villages for charcha over chai, you get the sense that people in Kairana know the importance of the May 28 bypoll. Kairana was one of 71 Lok Sabha seats that UP contributed to BJP’s 282 tally in the 2014 general elections, enabling the party to win its first majority in Parliament on its own. Kairana is close to Muzaffarnagar, the epicentre of communal violence that rocked the state in 2013. And in 2015, this was where the BJP alleged that Hindus were being chased out by Muslims.

The BJP drove into western UP, including Kairana, on the wheels of development and Hindutva. Now that a section feels ‘development’ has been derailed, it’s the durability of Hindutva that is under question. A combined opposition has fielded a Muslim candidate against the BJP, which would ordinarily have been an ideal situation for the Hindutva party to polarise the electorate along Hindu-Muslim lines. Clearly, the Kairana bypoll will test the Hindutva wheel and the opposition’s ability to dismantle it by coming together.

“There is anti-incumbency across castes as people feel the government didn’t fulfil its promises, and the gap can’t be sealed with Hindu sentiment alone. That’s the hallmark of this election,” says Samajwadi Party (SP) leader Sudhir Panwar, who has been campaigning for the united opposition candidate, Tabassum Hasan, a former SP leader. This dynamic has not just brought SP, the BSP, the Congress and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) together, but also emboldened them to field Hasan, a Gujjar Muslim woman, on an RLD ticket. Since the RLD draws sustenance predominantly from Jats, and it was in the Jat-dominated villages that the 2013 riots occurred, her selection is about political signalling. “It was a collective decision of mine and (former UP CM) Akhilesh Yadav, which we also discussed with other partners,” says RLD leader and former Mathura MP Jayant Chaudhary.

Kairana has 1.8 lakh Jat and 5.2 lakh Muslim voters. Muslims are not strangers to the RLD, but the SP and the BSP have weaned them away. “If we reinforce the idea that Hindus won’t vote for Muslim candidates and make Muslim exclusion from politics the new normal, then we would have to question what we really stand for,” Chaudhary says. If Hasan wins, Kairana and its neighbourhood will no longer be seen through the prism of riots. If not, it would demonstrate the RLD’s inability to transfer Jat votes to its alliance partners. On the other hand, if the BJP retains the Jat votebank, it would mean the party can still create a Hindu monolith and head for the Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and 2019 polls with an invincible aura against the Congress. “The pressure on us is from the bottom. Even if the parties fight over minutiae, our workers and those who want to vote for us are cementing this alliance,” Chaudhary says.

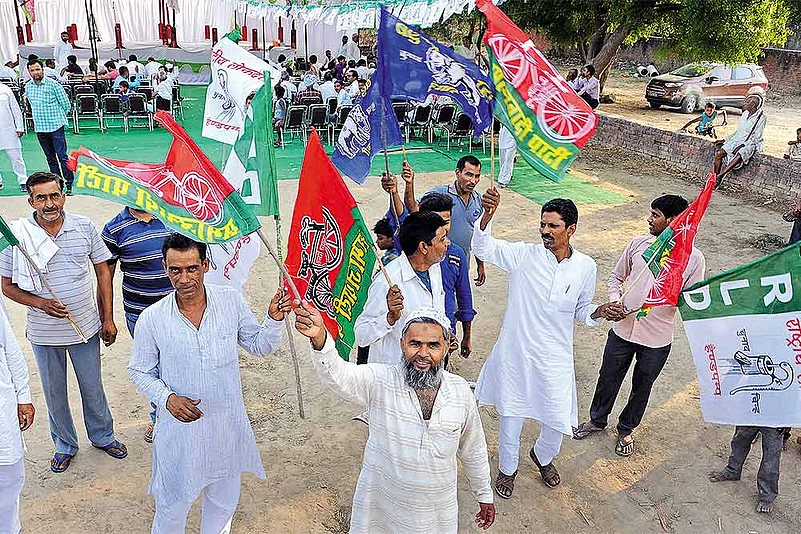

A meeting of notable Muslims, Dalits and Jats to cement ties

Indeed, what makes this a high-stakes bypoll is this attempt to not just cobble together diverse identities, but bridge the Hindu-Muslim divide as well. “Supporting the BJP led to political isolation, the Jats feel,” says Kuldeep Malik, a young Jat farmer from riot-hit Lak, who admits his community wants the BJP—the party he supports—cut down to size. “They will gather under the hand pump (the RLD’s election symbol) to save RLD chief Ajit Singh from political obscurity.”

Jat farmer Veersen says, “We can only see the hand pump, not the Muslim face behind it.” Another Jat Jaswant Singh says, “We would never have voted for the SP even though the BJP, which we had voted the last time, didn’t help us with the riot-related cases filed against our young men. The RLD helped us rebuild ties with Muslims and that’s a relief.”

But how many are really enthusiastic about a bypoll that cannot make or break the 2014 outcome? For Muslims, the alliance is a way out of political obscurity since the BJP’s rise. “Ramzan or sowing season, Hindu or Muslim candidate—our village will only vote for bhaichara. The Dalits are also with us,” says Zulfiqar, a Rangad or Muslim Rajput from Bunta village.

Mohan Lal, village head of Khedki in Shamli district, represents another key component of the alliance, the BSP, whose supremo Mayawati has asked the region’s 2.25 lakh Dalits to support Hasan. “This alliance is our attempt to send a signal for 2019 and bridge the gap between social groups. If we lose, it would put a question mark on whether any alliance can happen in 2019,” he says. Dalits, especially Chamars and Jatavs chafing under BJP rule, say they will back the alliance. The ban on transporting cattle for slaughter hit their livelihood and anti-reservation rhetoric threatens their prospects. The Bhim Army’s emergence in neighbouring Saharanpur in 2016 and its leader Chandershekhar Azad’s continued imprisonment is another factor prompting Dalits to show they can swing elections.

The BJP candidate is Mriganka Singh, whose father Hukum Singh was a Gujjar leader with a following beyond Kairana’s 1.2 lakh Gujjar and 1 lakh Saini voters. Not atypical for this region, Hasan and Mriganka share a common great-grandfather. The Gujjars say they have assured Mriganka their support. “The alliance candidate may be Gujjar, but she doesn’t even dare enter this village,” says Ramvir Kashyap of Kandela village, considered a BJP stronghold. As Hukum Singh’s death prompted this bypoll, some sympathy votes too may come Mriganka’s way.

Interestingly, BJP campaigners too have been talking of Hindu-Muslim unity—a sign, perhaps, of realising that caste can trump religion in western UP. “Mriganka Singh is our buaji. Barring the Jats, all communities in the entire constituency are with her,” says Madan Singh Chauhan of Jagatpur, a Gujjar-dominated village.

In Shamli town, the 2016 surgical strike in Pakistan, UP’s crime-fighting tactics, free cooking gas for poor households, Swachh Bharat toilets, demonetisation and PM Narendra Modi’s foreign outreach are creating a narrative favourable to the BJP. It is among farmers that Hindutva’s appeal has dimmed due to delays in clearing sugarcane dues, but it remains to be seen whether this affects just the Jats or the Gujjar farmers as well.

The BJP, no doubt, is keen to retain the seat it won in 2014 and has expanded beyond its elite-caste Brahmin-Bania-Thakur base—numerically small, but with a disproportionate power to influence narratives across the society. Non-elite castes such as Gujjar, Kashyap, Saini, Valmiki, Kori, Jogi and Jat too have supported BJP in the recent polls. “We have reached out to all as this is the last election here before 2019,” says Mriganka. “Every social group will vote for us. We must win.”

The critical factor in Kairana will possibly be the 15 to 20 per cent floating voters. Maybe that’s why PM Modi has chosen to visit nearby Baghpat a day before voting. In this scenario, where various social groups are trying to find a new equilibrium, the effect of his appeals will be tested too.

By Pragya Singh in Kairana