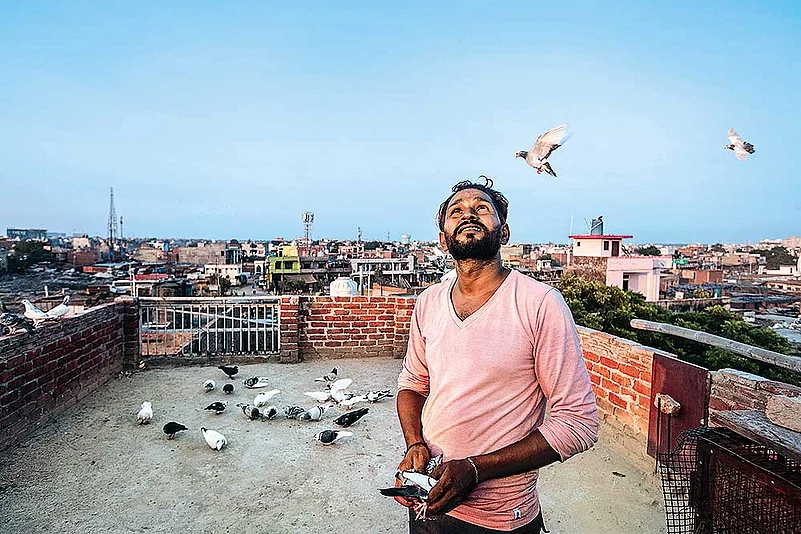

Manual scavenging is banned in India, but every day thousands of sanitation workers get into open drains, septic tanks and sewage lines across the country, cleaning muck, slush and human excreta manually—something despicable and unthinkable in a modern, civilised society. Technological advancements have made it possible to treat the waste in a scientific manner, without the need for anybody to do it manually. And yet, for someone like Vicky Pracha, the day begins and ends with a dip in the cesspool. Outlook follows the 37-year-old sanitary worker from Ghaziabad to record what it is like for those who have to put their lives and dignity at stake to keep our homes and habitats clean.

Vicky, born into an ‘untouchable’ Valmiki community that has been engaged in manual scavenging for centuries, converted to Christianity around 10 years ago—a step that brought little respite from the nature of his job. As a contractual sanitary worker with the Ghaziabad municipal corporation, his normal day begins at the crack of dawn, with a familiar task—to manually clear a clogged pit somewhere in the city. The only thing that has changed for him from the time he started doing this job about 17 years ago is his salary, which has risen from Rs 2,500 to Rs 7,500 per month—a pittance.

There are no fixed working hours for him. He can be called by the civic contractors at any time, from early morning to late night. Come rain or shine, he has to respond and clean the mess on a priority basis. He has to enter the drains barefoot and without a mask. He also has to inhale toxic gas and be in dirty, stinking water, but he now considers them unavoidable occupational hazards. There is, of course, a mechanised way to suck out the sewage, but it is hardly used. The drivers of the trucks carrying the equipment prefer manual operation to be done by the likes of Vicky. Every litre of fuel saved in the process is a few extra bucks earned for them—on the sly, of course. But he cannot complain against them.

The sole breadwinner in his family, every time he gets into an open manhole, he thinks he is entering a death trap. He knows 10 of his colleagues have died in about a month in Delhi recently. But he has to carry on, getting dunked into a drain overflowing with human excreta, regardless of the inherent dangers to his life. In the name of safety measures, all he gets is a so-called safety belt, wrapped around his body and tied to a rope before he embarks on his cleanliness mission. Deep inside, however, he knows the rope would be used only if he fails to return—to extricate his body.

This has been a family vocation for generations and the mindset of people towards it has hardly changed all this while. He has seen his father, a retired sanitary worker with the railways, doing the same. But he does not want his children to follow in his footsteps. A father of five, including four daughters, he has not told his children about the exact nature of his job. “They only know I am a safai karmachari,” he says. “At times, I think of giving it up, but I have to support a large family. I want to get my children educated so they do not have to lead the life I do.”

Vicky feels he is still treated as an outcast in society. “People keep a distance from me wherever I go to work,” he says. “I am always looked down upon. They even avoid touching the glass or the cup I have used.” It hurts, he says, but he prefers to take it in his stride. He knows the more things change, the more they remain the same. At night, he needs to unwind, invariably with a bottle, and forget whatever he has gone through the day. He cannot afford to let his frustration get the better of him. He has to get ready for work with the crack of the next dawn, which does not bring light into his life.

Photographs by Vijay Pandey