At the Razdhan mountain, there is no activity near the 330 MW Kishanganga Hydroelectric Power Project (KHPP), except for some labourers busy widening the road leading to Matrigam village, the nearest habitation. Government forces personnel deployed in a bunker keep an eye on anyone who ventures into the vicinity of the project site. Interestingly, there was no announcement for the locals that the project has already been commissioned, despite objections raised by Pakistan at the World Bank. On March 31, the government of Jammu and Kashmir issued a brief statement declaring that all three units of the “prestigious 330-MW Kishanganga HPP” underwent successful trial runs, and that the project was almost complete. The National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) issued a press release saying the third unit (110MW) was “successfully synchronised with the grid and…achieved its ‘rated full load’ successfully on March 30”, adding that it “marks the commissioning of all three units of Kishanganga project, as the first and second units have already been commissioned on March 13 and March 21, respectively”.

The project, for which construction had started in 2009, was initially scheduled for commissioning in November 2016. It was delayed due to the months-long unrest in the Valley following the killing of 22-year-old Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani in July 2016.

Neelum project in Pak

On Pakistan’s objections to the KHPP, Zahoor Ahmad Chatt, former director of J&K’s State Power Development Corporation (SPDC), says Pakistan insists it has the first right to the waters of the Jhelum’s tributary Kishanganga, as its 969-MW Neelum Jhelum HPP (NJHPP) downstream across the Line of Control (LoC) is under construction. According to the Pakistan government, the first unit of NJHPP is expected to generate 470 MW of electricity by April 13, and the other three units would become operational within a month after that. Islamabad has petitioned the World Bank contending that the Neelum project would be adversely affected by the Kishanganga one, which would restrict the amount of water available downstream.

"Work on the Kishanganga project started in the 1980s, long before Neelum.It was abandoned because of the armed insurgency that began in early 1990,” says Chatt. “The KHPP is not a storage scheme, but a run-of-the-river project fully in accordance with the Indus Water Treaty. The World Bank was convinced by our argument.” Pakistan has also objected to the 850-MW Ratle HPP, to be constructed by the J&K government in the Chenab Valley region of Jammu. This project is currently under arbitration.

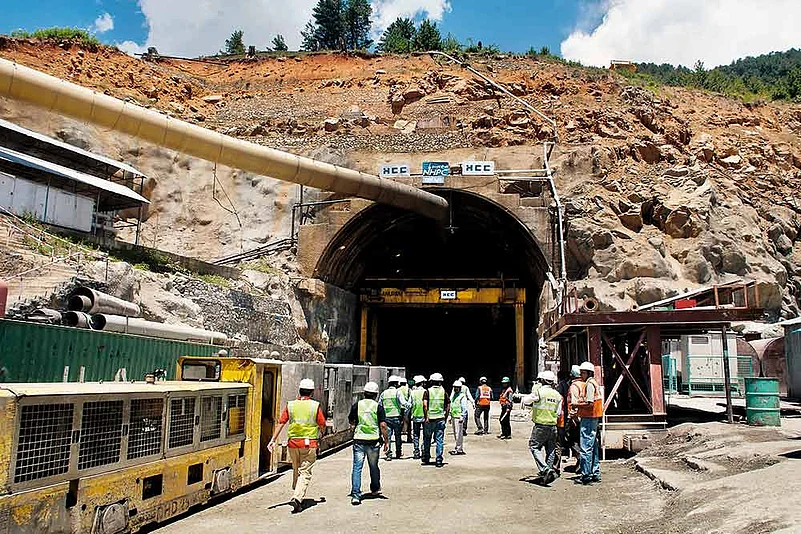

The KHPP was designed to divert the water of the Kishanganga, called Neelum in Pakistan, near the LoC, via a nearly 24-km-long ‘head-race tunnel’, to a power house inside the mountain, which would generate 1,713 million units per annum. The dam is located in Gurez Valley across the Razdhan pass. From the underground power house, the water would flow to Bonar stream and then eventually be drained into the Wullar lake. Officials say a 8.9-km-long tunnel from the dam side, with a diameter of six metres, was constructed using the conventional drill-and-blast method, and a 14.75-km-long tunnel under the mountain from the power house side, with a finished diameter of 5.2 metres, was constructed using a tunnel boring machine—the first time it was used successfully in the Himalayan region. “The entire project is underground, so you won’t be able to see anything except the power house,” says an NHPC official, adding that massive afforestation will be done in the years ahead to augment the green cover.

As Pakistan had opposed the construction of the Kishanganga and Ratle projects, the World Bank report of 2016 says the two countries disagree over whether the technical design features of the two hydroelectric plants contravene the Indus Water Treaty. The treaty designates the Jhelum, the Chenab and the Indus as “western rivers” to which Pakistan has a right of unrestricted use, while India is permitted to construct run-of-the-river hydroelectric power generation facilities. Pakistan had asked the World Bank to facilitate the setting up of a court of arbitration to look into its concerns about the designs of the two hydroelectric power projects. The NHPC, however, says the Kishanganga project was in accordance with a court of arbitration. “Apart from the many states that would be the project’s energy beneficiaries, 12 per cent of the power generated from the project will be provided to Jammu and Kashmir free of cost. The project is covered under the Indus Water Treaty signed between India and Pakistan,” the NHPC asserts.

J&K Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti tells Outlook that the state government would push for an increase in the royalty beyond 12 per cent. “Our government will pursue the demand that the royalty to the state on the projects run by the NHPC should be more than 12 per cent. We are taking this up with the central government,” she says. There is a potential of generating 20,000 MW in J&K, but only 2,000 MW has been harnessed by the central sector, mostly by the NHPC, and 1,400 MW by the SPDC.

According to the experts in the state, the Kishanganga and Ratle hydroelectric projects are not the only points of friction over water resources between the two nuclear-power neighbours. At the core of Islamabad’s technical objections to the power projects in Jammu and Kashmir, officials say, is the worry that India could cut Pakistan’s precious water supplies during the agricultural season. In fact, the Indian government has been sending out a subtle message that it may stop the water flowing to Pakistan if the latter doesn’t stop supporting militant groups in Kashmir. For instance, after militants attacked the Uri Brigade Heaquarters of the army in 2016, killing 19 soldiers, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had warned, “Blood and water can’t flow together.” Later, India suspended the scheduled meetings of the Permanent Indus Water Commission.

Officials in J&K say the Indian government is using the treaty provisions quite intelligently to mount pressure on Pakistan. “It has successfully whipped up the paranoia in Pakistan’s domestic politics that India is damming up the rivers upstream, and that it is a very important political issue,” says an official, who didn’t wish to be identified. “Similarly, all over India too, full advantage is being taken of this rhetoric that the government is using the western rivers as weapons against Pakistan. Yet whenever Pakistan approaches an international forum like the World Bank with a complaint, India quickly comes out with calculations to convince the international community that it is faithfully following the treaty, which it actually is.”

As an example, the official points out a March 24 statement by Union water resources minister Nitin Gadkari, who said the Centre would solve the water problems in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan by utilising water from the rivers flowing into Pakistan. The official says such statements are meant for the national audience only. “In fact, not even a fraction of the 3.6 MAF (million acre-feet) of permitted storage on the three western rivers has been utilised so far by the existing hydropower projects of around 3,300 MW on the Jhelum, the Chenab and the Indus, or elsewhere in any major irrigation or flood control project”, says the official. “This leaves India a huge elbow room to build a narrative around river dominance without even violating the provisions of the Indus Water Treaty. The optics are totally in India’s favour.”

Now, with the Kishanganga project and allotment of the 1,000-MW Pakal Dul project on the Marsudar river, Pakistan has found itself in a spot once again, while India is making a big show of it. According to sources, the central government is fast-tracking stalled projects such as the 800-MW Bursar, the 1,850-MW Sawalkote and the 930-MW Kirthai ones, causing consternation across the border.

Pakistan recently informed the World Bank about India completing the Kishanganga project during, what Pakistan calls, the bank’s “pause” period, and urged it to “recognise its responsibility” under the Indus Water Treaty. “It is shadow boxing going on. When this would escalate into a real fight and precipitate a full-scale confrontation between the two neighbours, no one can tell,” warns an official in J&K.

By Naseer Ganai in Bandipora