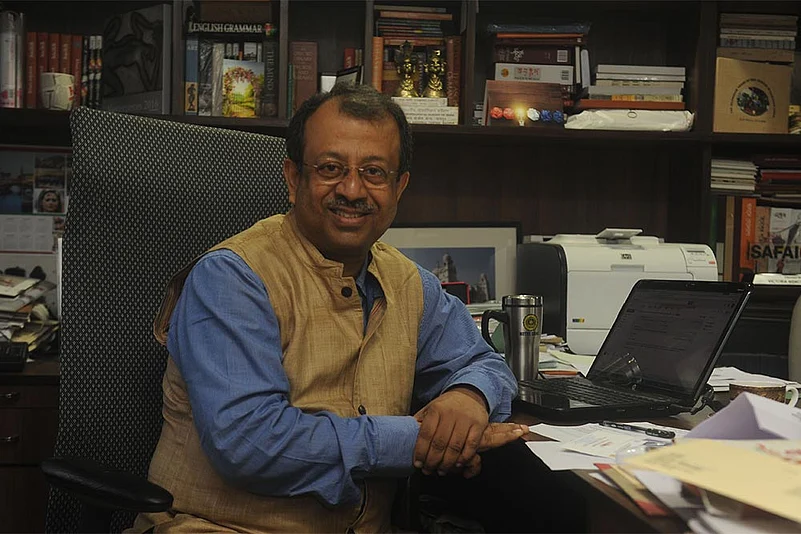

When the Indian Museum’s former director was forced to resign amidst wide-ranging allegations soon after a key scientist went missing, Dr Jayanta Sengupta, director of the Victoria Memorial, was given additional charge as director. The professor and scholar, who admits IMK continues to be besieged by “bad press”, answers the charges levelled against India’s oldest and largest museum.

Why has the Indian Museum (IMK) not taken initiatives to track down Dr Sunil Upadhyay, the chief conservation officer, who has been missing since July 2014?

The case is being investigated by the CID. I understand that IMK had cooperated fully with the agency during its inquiries. Since May 2015, when I was given additional charge of director, I have not had any occasion to deal with the probe.

Upadhyay’s family and some of his colleagues are asking for a CBI enquiry. What is the view of IMK’s top management?

Such decisions are not taken by us. IMK’s role is to assist in the probe. If the agencies need to question anyone we are duty bound to comply. If they require any documents or records we must provide these. Such matters are routine. But the CID has not shared anything regarding the status of the case with us. In fact, in another, nearly 13-year-old case regarding the theft of a priceless Buddha idol from IMK, the CBI has not submitted any report that we know of.

Upadhyay is understood to have raised uncomfortable questions pertaining to a host of ills supposedly plaguing IMK, including corruption.

I have heard such claims but by the time I was given charge, he was no longer there.

IMK has received a grant of Rs 99.76 crore for a “renovation and modernisation” project from the Union ministry of culture on the occasion of its bicentenary. There are allegations of “misappropriation of funds”, against the management.

By May 2015, when I joined, most of the “modernisation and renovation” project work had been done. The grant money too had accordingly been more or less spent. As regards “misappropriation”, I think the expenditure structure is designed in such a way that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, for any IMK official to steal from the grant money. While the grant had been received in the name of IMK (electronically transferred into its accounts with the SBI) and IMK is the sanctioning authority, the responsibility for implementation of the project is vested with another independent agency, the National Building Construction Corporation (NBCC). They receive the grant money from the IMK as per their requirement. They determine the exact amount needed, ask for it from IMK and are paid accordingly.

According to a letter from Saumyo Mukherji, a former IMK employee addressed to the governor, the grant was meant to be utilised by 2014, but it has not been done.

As I said, when I arrived in May 2015, work was at its tail end. But there had been a set of obstacles in its completion because of certain structural problems. Though the museum owns the premises on which it stands, it comprises a number of other survey buildings that are independent and come under different ministries of the government of India. This posed a complex problem, because any works in these would entail negotiations between and permissions from these ministries. Our rare collections also need to be handled with great care, so we must not lose perspective.

Interestingly, IMK employees and former employees have complained to higher authorities, including the governor, about the museum’s negligent treatment of rare collections of art and artefacts.

In 2014, one of IMK’s most valuable possessions, a 2nd Century BC sculpture, the Rampurva Lion Capital, was damaged, possibly because of mishandling. The unfortunate incident has made employees who handle the collections extra careful.

Workers also complain that lack of CCTV cameras expose collections to theft.

There are currently around 400 CCTV cameras at IMK. Perhaps a few (around 20 to 25) are not functioning properly. I personally oversaw the installation of over a hundred cameras.

How do you reply to charges, as levelled by the former legal consultant, that recruitments at IMK do not follow protocol?

Several RTI applications filed with the IMK before I was given charge do pertain to ‘irregularities’ in recruitment. Currently, there is a stay order by the Calcutta High Court on recruitment because of a case related to a hiring.

You have initiated a number of cultural projects at IMK, introducing the performing arts as part of the museum’s cultural activities. But this is overshadowed by these allegations. Your comments.

When I was given additional charge Indian Museum was steeped in “bad press”. I am aware of the many hiccups in the way that business was conducted for long. I have been trying to address these. Some problems have been solved; others still need attention. But since I have arrived, I have endeavoured to turn it into a kind of cultural “hang out” zone. I was inspired by the success of similar programmes I initiated at the Victoria Memorial. IMK is India’s largest, oldest museum and houses one of the world’s rarest collections. One of the ways in which I thought that we could turn the spotlight back on it was to turn it into a locus of cultural activities.