Against the backdrop of snow-capped Himalayan peaks, an undulating green valley stretches as far as the eye can see. Sheep graze in the distance, under an azure sky. Tufts of cotton-cloud drift lazily overhead. A gurgling mountain stream skirts past one edge of the land. A few foreigners, all tourists, form a line in the distance as they trek through Tosamaidan, soaking in the breath-taking beauty of the picture-postcard meadow.

But less than a decade ago, Tosamaidan—in the Pir Panjal mountain range in Kashmir valley—was a living hell, a purgatory at a place once lovingly called the “heaven on earth” by Emperor Jahangir. Used as a live firing range by security forces, including the army and BSF, the 11,200-hectare Tosamaidan resembled a war zone. From April to November every year, the army fired artillery shells from different villages of Budgam above the Pir Panjal mountain range towards Tosamaidan. At times, the live ammunition would land outside the firing zone, leading to human casualties. The government says at least 65 people have died in Tosamaidan in separate incidents. However, residents say the number of dead people could be far higher as the victims’ kin often refrained from registering FIRs.

In 2014, the Omar Abdullah government refused to extend the lease to the army for using Tosamaidan as a firing range, in response to the massive public protests. The decision brought relief to people, stopped killings due to shelling and brought tourism to the area. And all credit for the turnaround goes to the Tosamaidan Bachao Front, an organisation that emerged from the public protests, galvanised the public and institutional support for closing the meadow for live fire training. The Indian Army and other forces had been using the meadow as an artillery firing range since the 1960s.

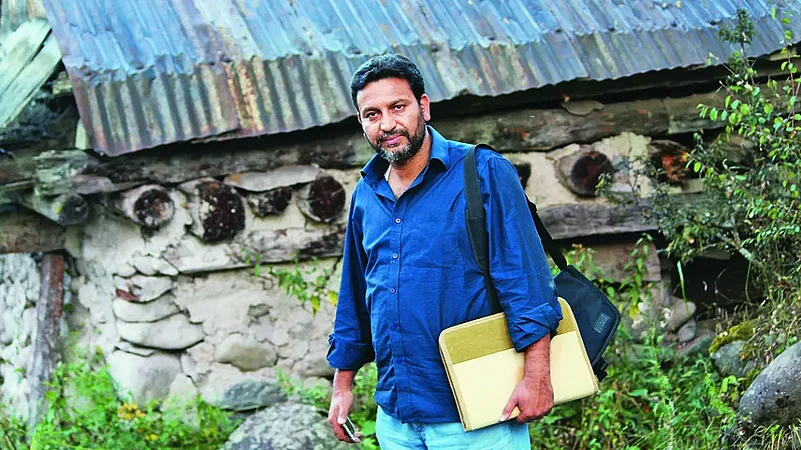

Dr Shaikh Ghulam Rasool, founder of the Front, saw the horrors of the shelling when he was posted as a doctor in the area way back in 2005. “I visited a village and found a number of people killed by exploding shells. People on routine work would walk over an unexploded shell. The shells would either kill people or would maim them for life,” he says. As instances of human casualties increased, Rasool started to mobilise people of the area against the firing range. He found support from Sheikh Ghulam Mohideen, who went on to become the sarpanch of the Sithharan village. “(But) people were earlier reluctant. They were not ready to talk about it, fearing reprisal. But we convinced them that it is our democratic right to protest as a large number of villages were affected,” says Rasool, 45. The villagers joined the movement, and gradually political parties too started supporting the people.

After the area was cleared of explosives, the government started promoting the meadow as a tourist destination. In May, 2016, then chief minister Mehbooba Mufti approved community-driven tourism in Tosmaidam. “We have covered a large area under the afforestation programme and a large number of tourists are visiting Tosamaidan,” Rasool adds. “My only worry is that Tosamaidan shouldn’t become another Gulmarg. It should remain a vast meadow, devoid of hotels and a destination for community-driven tourism,” he adds.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Paradise Regained")

Liked the story? Do you or your friends have a similar story to share about 'ordinary' Indians making a difference to the community? Write to us. If your story is as compelling, we'll feature it online. Click here to submit.