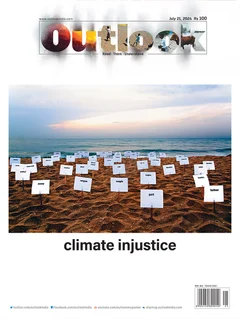

On a crisp, sunny morning last month, a crowd gathered at Dilaram Chowk in Dehradun. Students, senior citizens, working professionals, homemakers, activists—all galvanised by a common cause—to save the trees in their hometown. Nestled at the foothills of the Himalayas, green canopies used to be a given in Dehradun. But the ecosystem of Uttarakhand’s capital is in danger due to excessive felling of trees and rampant construction. Acutely aware of this, the protestors at Rajpur Road went on a 2 km march that morning, holding up placards. The slogans written in bold on the cards expressed their sentiments loud and clear. They were opposing a road-widening plan that would involve axing 240 trees, including one that had been part of the landscape for 250 years. The march was the culmination of a campaign that mobilised concerned citizens in Dehradun to step up. Not long after the march, the administration announced that it was dumping the road-widening plan. Public sentiment had won the battle.

People’s movements—from Kashmir to Kerala—are making strides. Volunteer-led efforts such as the Save Aravali Trust in Haryana whose members plant trees in the Aravalis that are ravaged by deforestation and mining; the Save Mollem movement in Goa, launched by citizens to protect Mollem National Park and Bhagvan Mahaveer Sanctuary from the fallout of massive infrastructural projects; and the Kali Bein river clean-up in Punjab by the locals are just a few examples. Veteran anti-mining activist from Odisha, Prafulla Samantara, thinks people’s movements are “inevitable” at a time when the majority of politicians serve corporate interests at the cost of common people. These movements give vulnerable communities—Adivasis, Dalits, struggling farmers—the courage to assert their rights over natural resources.

Many battles are being fought against impossible odds. Acts of resistance—everyday ones that never make the headlines and emphatic moves that attract the spotlight—are unfolding across the country as fragile ecosystems and livelihoods of marginalised communities come increasingly under threat. “Overuse of natural resources like water and raw materials plus the injury inflicted on nature in the name of development have caused serious environmental issues,” says Sagar Dhara, co-founder, South Asian People’s Action on Climate Crisis (SAPACC). “Environmental movements are asking for equity between species. They shake up the very basis of the social structure and the economy,” he adds.

***

Acts of resistance are unfolding across the country as fragile ecosystems and livelihoods of the marginalised come under threat.

Environmental movements gained visibility in India in the 1970s at around the same time they were coming to the forefront in European countries and North America. Among the most memorable Indian movements are the Chipko movement (1973) sparked by rural women in Tehri Garhwal to save forests from logging; the Save Silent Valley (1978) movement in Kerala; the stance of the Bishnois in Rajasthan against tree felling and wildlife hunting (1970s); the Jungle Bachao Andolan (1982) by Adivasis in Singbhum district, Jharkhand; the Appiko Movement (1983) that was born in Karnataka to protect the forests in the Western Ghats; the Narmada Bachao Andolan (1985), which began by demanding rehabilitation and resettlement for people displaced by the dam; and several movements against globalisation in the 1990s to safeguard natural resources—the source of livelihood of tribal communities.

“The ‘environment’ encompasses everything around you: housing, livelihood, biodiversity, your work conditions, the air you breathe, the food you eat,” says social activist Nityanand Jayaraman. “Those from disadvantaged backgrounds are disproportionately affected by environmental degradation and climate change. People’s movements are fighting to secure their present. To make sure they are not evicted from their homes and land. To ensure they don’t lose their livelihood or get beaten to a pulp for not giving up their land or breaking some rule imposed on them.” Rahul Yadav, who has been working with the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA) in Madhya Pradesh for 15 years, says he has several court cases pending against him. According to him, all of these are trumped-up charges, concocted by those in power since he is part of a longstanding people’s movement.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The law is often used to intimidate those who are affected by mega projects or refuse to make way for them. When a wave of protests broke out in 2011 among the fishermen and farmers of Kudankulam and Idinthakarai villages in Tamil Nadu against the Kudankulam nuclear power plant, many protestors were charged with sedition. Some were booked in cases registered under Section 121 (waging or attempting to wage war, or abetting waging of war against the Government of India) of the Indian Penal Code. In May 2018, 13 people were killed at Thoothukudi in Tamil Nadu when the police fired at a crowd of demonstrators demanding the immediate closure of the Sterlite Copper plant. They were protesting against it over pollution.

“Irrevocable environmental damage is being done in name of ‘development’, which has become a holy cow,” says conservationist and author Prerna Singh Bindra. “Grassroots environmental movements and environmentalists are often maligned as they raise questions—‘whose development’ and ‘at what cost’, but protecting the environment is foundational to our ecology, economic security and health.”

According to advocate Harish Vasudevan, very few legislators bring the questions raised by people’s movements and civil society groups to Parliament. So, the voices of those affected (especially the most vulnerable) by the climate crisis are hardly ever aired there. The other major cause for concern is the “huge gap” in environmental legislation. There is no lack of laws regarding the conservation and protection of the environment. But implementation is lax and when courts issue orders, corresponding penal provisions are missing most of the time. For example, the Western Ghats is being overrun by exotic species, but there are no statutory provisions to punish the people who plant these trees there. Another instance: the Forest Conservation Act. “How many cases have been registered so far against officials who violated the Act?” asks a frustrated Vasudevan. “Orders are passed but if they are not carried out in a timely manner, it will be too late,” says Vasudevan. “Protecting the environment is a timebound affair…And we are running short of time.”

***

Some sceptics say that for every environmental movement that succeeds in India, there are nine that fail. Taking on giant corporations or the almighty state is a skewed battle from the start. People can get exhausted along the way, and funds to keep the fight going are scarce. Volunteers involved in activities like afforestation or clean-ups of rivers may lose steam. A slew of court cases and the challenges of navigating red-tape ridden waters can eat away at even the most committed person’s morale. All of this may be true. But it is equally true that people’s movements leave a lasting legacy and influence policy change.

The anti-mining movements in Goa, Karnataka and Odisha; the protests in Kudankulam led by S P Udayakumar and his People’s Movement Against Nuclear Energy; the Adivasi movements for jal, jungle, jameen; the villagers’ struggle against a corporate giant’s water-guzzling plant in Palakkad’s Plachimada; the people’s movements that have stood up (and continue to do so) against pollution and demanded compensation for the affected at places such as Bhopal, Dahanu, Udupi and Bichidi—have all challenged the status quo and rewritten the dominant narrative about development to a great extent.

Jayaraman argues that we need to use a new vocabulary when assessing the ‘success’ and ‘failure’ of people’s movements. If a movement to shut down a nuclear power plant or a factory that pollutes the air and water resources of an area does not force its closure in the end, does it mean the movement has failed? If the sustained efforts of a citizen-led campaign cannot prevent a forest from being chopped to make way for a high-speed rail project, is the campaign to be dismissed as a failure? “What movements do is make a statement; create a churning,” says Jayaraman. “They highlight the possibility of a variety of futures. That’s their real ‘success.’” Prafulla Samantara points out that people’s movements are invaluable because they send out the most urgent message of all: “In a world reeling from the damages caused by climate change, humanity has to protect nature to ensure its own survival.”

Every movement matters. Every churning creates change. Minaxi Sharma of the Save Aravali Trust, who trudges up the Aravalis with her coworkers on the weekends to return the mountain to its former green glory, agrees. Rahul Yadav of the NBA understands that people’s movements across the country have very specific local concerns. “A movement in Haryana will be dealing with a different issue from one in Goa or Manipur,” says Yadav. “But we shouldn’t be working in silos. Our common concern is the environment. If we come together under one umbrella, we would be a formidable force that can influence politicians’ decisions.”

(This appeared in the print as 'We The Power')