Diasporas can be classified into two broader categories: regular diasporas and defiant diasporas. Regular diasporas strive to create their own comfortable niche in their host countries and stand for all that is good and presentable about their country of origin. Defiant diasporas, while treading a similar path vis-à-vis material aspirations, also act as agents of social-political change in their home countries. Both diasporas are part and parcel of the same broader outbound ethnic groups—in one way or the other, both facilitate economic, social and political exchanges through their transnational networks. But, in a nutshell, while regular diasporas conform to the social-political status quo in their home country, the defiant diasporas assert and agitate against the persecutions from home countries and insist on creating just and egalitarian society in their native countries.

The main characteristics of defiant disaporas are as follows: they refuse to be part of the ruling government’s propaganda that whitewashes the harsh social-political realities of their home countries. They lobby, campaign and raise awareness in their host countries about the discriminatory social practices and perceive the systematic persecution, ethnic profiling, political suppression and state impunity—often pointing out that the tag of ‘anti-national’ is wrongly applied on the victim. Yes, they use international pressure groups and seek legal help from bodies such as the UN. But while doing so, they do not necessarily compromise the sovereignty of their country of origin—on the contrary, they are more sensitive to the issue of going against the grain of the unity of their nation of origin.

Here, we are going to talk about one such prominent defiant diaspora: the Ambedkarite Diaspora the UK.

Since the known history of human migration, diasporas have been shaping the political destiny of their motherlands, making, unmaking and remaking nations with all their creative force. Be it the biblical account of the Jewish exodus and their search for a return to the Promised Land, or the great pan-Africanists of the last century, or the political activism of more contemporary times, what they demand of themselves and the world is political change in their homelands. This can be seen across the diasporas. These well-known historical endeavours should suffice to make us alive to the creative potential in them—they are not merely migrants making a ‘home away from home’ or making a new ‘desh’—i.e. a new homeland in distant, salubrious lands, ‘pardesh’ as creatively described by the anthropologist Roger Ballard.

Historically recent Indian diasporic movements began in the 1830s as indentured labour shipped out under the aegis of British colonial masters. They presently constitute about 18 million people across the world. The latest in that stream are the professionals and information technology specialists who have joined middle-class and elite sections of modern Western societies. Almost twenty years ago, Parekh expressed his dismay over the “fairly thin corpus of literature on Indian diaspora, uneven in quality” (Parekh et al 2003: Preface) which “should have been the subject of comprehensive exploration from the social, cultural and economic point of view”. By now, however, the Indian diaspora, with its varied origins, from former indentured labourers to what are presently influential communities in their receiving countries, have been the subject of several essays, articles and ethnographic research. What has not received attention is their role—or lack of it—in utilising their privileged position and economic strength to bring about social-political change in their country of origin, or to assert their affiliation to principles of equal human rights and social justice abroad. Conversely, the role of the India diaspora in maintaining and reinforcing the uneven hierarchies and the status quo of traditional power structures in Indian society warrants research attention.

In a real sense, the entire diasporic Indian communities out there have been agents of social mobility for their communities in their home countries via remittances, and often they have also influenced political assertions and strengthened social movements. From that limited perspective, we can say more or less all diasporas mentioned above have been engaged in political, cultural, and economic exchanges with their respective countries according to their ideological leanings and political stakes in their country of origin. But that’s where the distinctions start.

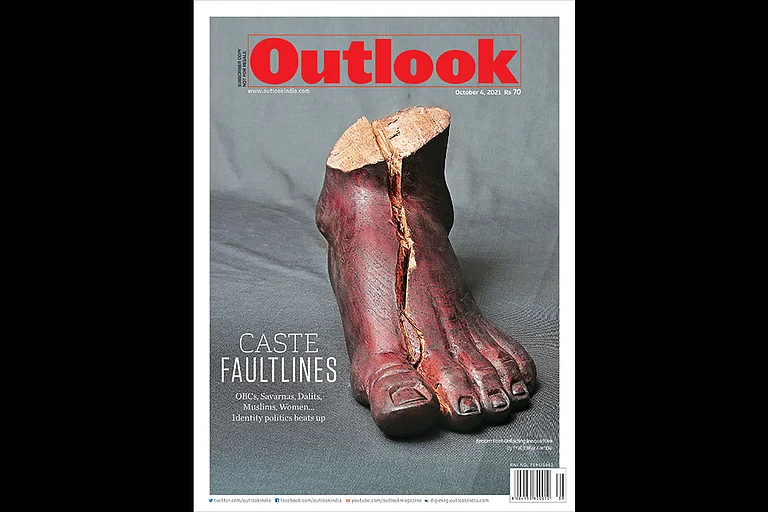

Ambedkarites abroad earned their title of being a defiant diaspora not only because they have been persistently challenging the mainstream narratives of India and Indians abroad, but they have been speaking truth to the Indian government irrespective of the ruling party. Whether it was Gohana atrocity in Haryana, or the Khairlanji lynching and rape, the Mirchpur genocide, the CAA-NRC protests, or the latest act of inhumanity in Hathras. The Ambedkarite diaspora was always in the forefront of registering protest and resistance. The life events of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, now celebrated across the world, form rallying points for all global Ambedkarite diasporas, whatever wide sub-regional variations they exhibit—Punjabi, Hindi, Tamil, Malayali, Gujarati or Marathi NRIs. Their primary attention has been to take everyone’s attention beyond the aura of wellness exuded by propaganda—which is a massive ideological enterprise executed by state and non-state actors and comes visually/culturally armed with the halo of Bollywood. The idea that ‘all is well’ in India is a piece of narrative that covers social pathologies, excuses the government from scrutiny of its state impunity, and keeps atrocities away from the global eye by calling it an ‘internal matter’. The Ambedkarite diaspora, along with the Sikh diaspora, has been actively lobbying and resisting in the embassies, councils, and parliaments of their host countries about the wrongs being done to their communities back home. The joint resistance of the Ambedkarite and Sikh diasporas even forced Prime Minister Modi to cancel his official tribute to Gandhi’s statue in London in August 2018, and his potential inauguration of Ambedkar House in London.

I have been closely associated with the defiant diasporas in the UK. Punjabi, Malayali, Marathi, Gujarati Ambedkarite NRIs have been actively participating in these processes of socio-cultural change and political activism. They run schools in their native villages, and regularly contribute to the cause of education by sponsoring poor students. I have also contributed to such active campaigns for many years.

The Ambedkarite diaspora is not monolithic in nature. It is a rich, varied dish that mixes cosmopolitanism and multiple faiths and intertwined identities. They also go by Buddhist, Ravidasia, Valmiki and Christian affiliations, besides their regional identities. Even the Buddhist ones include Punjabi, Marathi, Hindi and Gujarati-speaking groups, but whatever their group identities, all of them consciously abide by and contribute to Ambedkar’s ethos of striving for self-respect. Among the non-Buddhist Ambedkarite communities, there are Shri Guru Ravidas Sabhas and Bhagwan Valmiki Sabhas in the UK, there’s the European Union of Periyar Ambedkar Comrades Federation, and the Voice Of Dalit International.

Over a decade, I have observed that the Punjabi Ambedkarite leadership in the UK acts as a backbone of social-cultural-religious assertion and activism not only in Punjab but also all over India. The Ambedkar Sena, an organisation of well-educated Ambedkarite youth in Punjab which is quite aggressively vocal against violation of the human rights of victim castes, also draws its ideological and political inspiration from other elements, including diasporic returnees and the broader pan-Indian Bahujan social movement.

Diasporic community leaders from East and West London, Wolverhampton, Birmingham, Scotland and Ireland annually visit India where they run various projects and act as patrons. Some of these projects involve running secondary and higher secondary educational institutions. Others run schools with hostel facility for students from poor backgrounds. These community leaders are transnational activists who are respected professionals, businessmen or executives who want to pay back to society as part of their commitment toward the mission statement of Dr Ambedkar. They draw great respect from the local communities, who benefit from their projects, as well as from diasporic communities abroad—setting off a virtuous cycle of change. These transnational Ambedkarite activists who visit India often wear their prosperity, their lavish houses and rich lifestyles on their sleeves—the purpose is to inspire the young generation in their native villages and act as a role model for a spirit of aspiration to be built.

The inspirations

Take a few examples. Mulkiat Singh Bahal, an Ambedkarite NRI and transnational leader, is in the fashion business: he owns an iconic showroom in the legendary Oxford Street in London. Mr Bahal, who belonged to the lowest rungs of Indian society, reminiscences how as a child he was crazy about aeroplanes—he would go about chasing little steel flying machines while his mother went for her job as a sweeper. He told me how the young who live in India’s shanties listen to his speeches on the occasions of April 14 and December 6, the two markers of Dr Ambedkar’s life. Bahal has been one of the leading transnational activists since 1991, the centenary year of Babasaheb’s birth which was celebrated on a grand scale in London, UK. Mr Ginda from Scotland runs a hostel school in a village near Nagpur as part of a joint project. Mr Ginda, invested with a quiet demeanour, has been selflessly helping out this cause financially as a family project for years now.

H.L. Virdee, an international Buddhist Ambedkarite leader felicitated by Royal Head Monk Sangharaja Thero, also visits India annually. He has played a key role in building a Buddhist vihara, named Taxashila Vihara, in Jalandhar—styled after the great Stupa of Sanchi. Mr Virdee, who has a mansion in India adjacent to the vihara, is a patron of a training centre for Buddhist nuns and another vihara in Pondicherry. He is also a writer who publishes booklets on a no-profit basis in order to create awareness among society.

Gautam Ramji runs an Ambedkar centre in West London—it has turned out to be a hub of social-cultural activities for new arrivals, irrespective of caste and creed, and could be said to be a secular centre in true sense of word. This centre too houses a Buddhist shrine and a library, besides accommodation for guests and students from India.

Another renowned name among the Ambedkarite diaspora is a second-generation community leader from East London, Satpal Muman, who heads an anti-caste organisation called CasteWatchUK and the Ambedkar International Mission, UK. Mr Muman, a key public speaker and orator fighting against caste apologists like the Hindu Council UK in the English electronic and print media, has consistently spearheaded the fight for anti-caste legislation—and can often be seen participating in anti-caste conferences and workshops in the British parliament and other public places and media.

Ms Santosh Das, a retired civil servant, is an Ambedkarite community leader and founder of ACDA (Anti Caste Discrimination Alliance). She has been instrumental in lobbying with the Indian government and the Camden town council, London, to purchase and declare Ambedkar House, London, as a memorial and Museum (this is the place where Dr Ambedkar stayed during his studies at the London School of Economics in 1921).

Recently, Ambedkarite diasporic groups also teamed up to alleviate the sufferings of slum-dwellers, and local and migrant labourers in the unorganised sector during the peak of the Corona pandemic. Almost all the active centres of the Ambedkarite diaspora, plus independent ad-hoc groups formed on Whatsapp, plunged headlong into the task of financially helping the poor people from their own localities back home. These group members appointed trusted coordinators in India, mostly college students or social activists operating at the grassroots. These coordinators were entrusted with the job of setting up distribution stalls that gave out food, grain, and medical supplies like disinfectants. All help possible was rendered to those stranded during the labour migration caused by the lockdown. The entire operations were coordinated and monitored via Zoom meetings and video conferencing. The online space has now turned into a rich platform for diasporic activism—how the social media galvanises politics is a good area for further investigation.

The Ambedkar Memorial Committee from the Midlands has a central role in all this—as one of the oldest Ambedkarite Buddhist organisation here, other than the Ambedkar International Mission in East London and the Ambedkar Centre in Southall, West London. Places like Birmingham, Scotland, Wolverhampton and Kent remain strong ideological and cultural centres of Ambedkarite philosophy and politics.

These defiant diasporas have become ambassadors of bilateral friendship and peace between their country of origin and country of stay. There are some exceptions like the Kashmiri subsection and a minority of the Sikh diaspora that tilt towards the demand for a separate state, although they only get marginal support and minimum acceptance.

The Ambedkarite diaspora can be distinguished from the rest of their Indian compatriots through their very defiance, and insistence on making their country of origin accountable for atrocities. The lived experiences of the above-mentioned defiant diasporic communities with basic good governance in the UK—along with the multicultural, liberal and egalitarian ethos of contemporary English society—inspires them to seek the same in their country of origin. Their defiance actually springs from the teachings of their leader and liberator, Dr Ambedkar, and their great expectations from their motherland. That is why one can confidently say the monolithic images of diasporas as mere settlers abroad, which prevails in common perceptions, are incomplete and seriously flawed as they do not take into consideration the political agency of the diasporas.

(Shrikant Borkar, an alumnus of the University of Sussex, is working on a monograph entitled Nation, Nationality and Nationalism in India.)