River flows from Uttarakhand provide a myriad of ecosystem services including supply water for agriculture, industry, and domestic use, support biodiversity including endangered species (like dolphins, turtles, gharials and fishes) enrich floodplains, recharge groundwater, and sustain local communities, both within state and beyond.

Some of the perennial rivers of Uttarakhand are but increasingly turning seasonal, especially in the lower slopes and plains. Pollution, land use change, excessive pumping of groundwater and climate change along with extreme events are impacting the characteristics and functions of the rivers in most cases. Flooding in monsoons and decreasing flows in lean seasons are impacting both human and aquatic life.

Amid growing realisation of how river systems deteriorated, studies have been conducted in the state analysing the characteristics and ecosystem services of selected rivers in terms of water security, livelihood dependencies, river health and aquatic biodiversity profiles. Over 3,000 plus rivers traversing a length of 23,000 km were mapped by our team of which 85% of these rivers turned out to be less than 10 km long but are critical for hydrological and ecological health of bigger tributaries.

Small to medium length rivers (10-100 km) accounts for 80% of the length assessed and carry 15% of volume whereas long to very long rivers (>100) contribute 20% of length but carry 85% of volume. All these rivers are crucial for the well being of people and nature through water security and livelihoods for communities and provide habitats to aquatic biodiversity.

If we maintain these riverine flows, we will not only ensure that the Ganga and its tributaries continue providing ecosystem services but also stand to protect and conserve the national aquatic animal, Gangetic dolphin, the turtles, gharials, otters and other avian and floral biodiversity sustained by them and contribute in achieving the vision of Aviral and Nirmal Ganga.

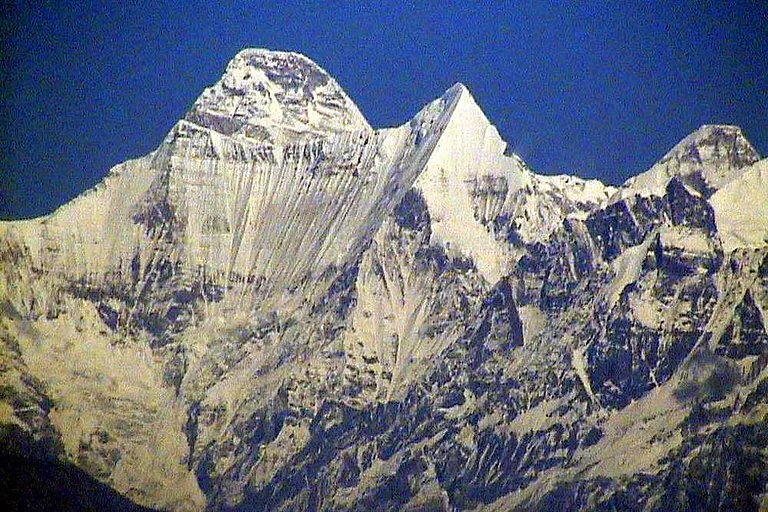

The Indian Himalayan region is home to unique high altitude wetland (HAW) ecosystems. HAW is a generic term to describe “areas of swamp, marsh, meadow, fen, peat-land or water bodies located at an altitude higher than 3000 m, above mean sea level (AMSL), whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or saline”.

They are extreme ecosystems, characterised by adverse climate and the presence of a seasonal or diurnal permafrost layer. The high-altitude wetlands are fed by snowmelt, precipitation and springs, unlike lower altitudes lakes, which receive water from local rains, through streams and runoff. The atlas of high-altitude lakes by Space Application Centre identified 4,699 high altitude wetlands in the country. Most of the wetlands are less than 2.25 ha in size while only 12 lakes are >500 ha, categorised as very large, have been observed, the largest being 29345 ha.

The National Wetland Atlas (High-Altitude Lakes of India) identified 118 high altitude wetlands in the state, covering an area of 231 ha. Even though small in size, these wetlands, being located in the basins of major river systems, are key to the water security of the region and contribute significantly to the local communities. Furthermore, they provide livelihood and are used for grazing livestock, and are considered biodiversity hotspots with rare endemic species of birds, medicinal plants and mammals.

Any change to the ecology and dynamics of these wetlands impact fish populations, agriculture, river infrastructure, flood cycles and communities in those areas. Furthermore, it impacts the fragile ecosystem that supports the rare and endemic species of flora and fauna. It is therefore essential that these HAWs be conserved and preserved for posterity.

Wetlands in all districts of Uttarakhand play a role in the drinking water supply of the area; they serve as recreational sites owing to their aesthetic value and provide an ideal habitat for biodiversity. Wetlands surveyed in all districts, except for Bageshwar district and Corbett Tiger Reserve, aid in floodwater storage. Similarly, barring Bageshwar district and Rajaji National Park, wetlands in other districts are a source of water for irrigation.

Most of the wetlands also serve as environment education sites for academic institutions. Most of the wetlands below 2,500 MASL play a significant role in drinking water and are also critical for biodiversity. The wetlands surveyed in Champawat and Corbett Tiger Reserve also contribute towards groundwater recharge. Uttarakhand also has one RAMSAR site, Asan Barrage, a wetland of international importance that supports habitat for several key avian fauna.

Over a hundred of these Himalayan wetlands are in Uttarakhand alone. Though small in size, they rate high in the scheme of things. Not only does the local community bank on them for its water and livelihood, so do birds, fish and the livestock that graze along its banks. Biodiversity hotspots host rare species of birds, medicinal plants and mammals.

It would be unwise to play with the ecology and dynamics of these wetlands. The dependent humans, avian species and fish are bound to suffer. Many of the wetlands in the state are already under deep stress. Climate change, excessive grazing, siltation and increasing tourism are impacting these ecologically significant wetlands.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Active management of these vital natural resource is needed so that things don’t deteriorate further. Local communities that bank on these wetlands need to be drawn into these important conversations. The authorities need to engage them as wetland mitras, ensuring that they truly befriend these water bodies and help preserve them. Trained and capacitated wetland mitras, including local van and gram panchayats, and authorities will be able to implement wetland conservation and restoration works more effectively to keep their wetlands healthy and continue to provide ecosystem services.