Have our police gone mad? Are they being swashed by the waves of cow-vigilante violence and bloodcurdling anti-Padmavati war whoop? Or are they being influenced by the cult of violence, spreading allegedly for electoral gains? Suddenly, several instances of custodial deaths and brutish behaviour have surfaced along with cases of shoddy investigation, suggesting that policing is in a deep crisis in India. The CBI had to arrest the investigating officers for the custodial death of an accused in the Shimla rape and murder case of July. In Maharashtra, on November 7, Aniket Kothale was found dead in custody after his arrest by the Sangli Police, who tried to burn his body with the help of a mysterious “zero police” (non-official volunteer).

The police are often seen to be in a hurry to claim success where the investigation is shoddy. Eight-year-old Pradyuman Thakur was found murdered on September 8 at Ryan International School, Gurgaon. The local police had claimed success following a bus conductor’s “confession”, only to have the claim trashed by the CBI on November 8 with the probe turning towards a Class XI student from the school.

Sir W.H. Sleeman (left) took on the ‘thugs’ in the 19th century

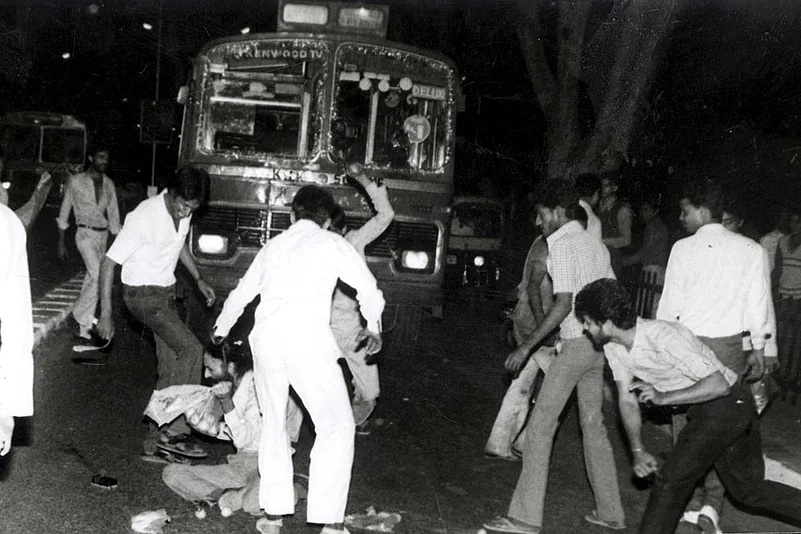

The most disconcerting is when the police behave brutally without an apparent reason. On November 2, for example, policemen in Mumbai were seen beating fans of Shahrukh Khan, who had assembled to greet him. On November 16, an off-duty policewoman was caught on camera kicking an elderly woman at a Thane temple near Mumbai for pointing out that her dress was “improper”.

I am not worried about the criminality of a few hundred wayward elements among our 30-lakh-strong police force. What is baffling is why several ordinarily law-abiding police officers are found using unreasonable violence during crowd control or custodial interrogation. Is it a short cut to time-consuming questioning, which may take hours if not days? Do the media egg them on? Why are they so uncivil towards ordinary citizens?

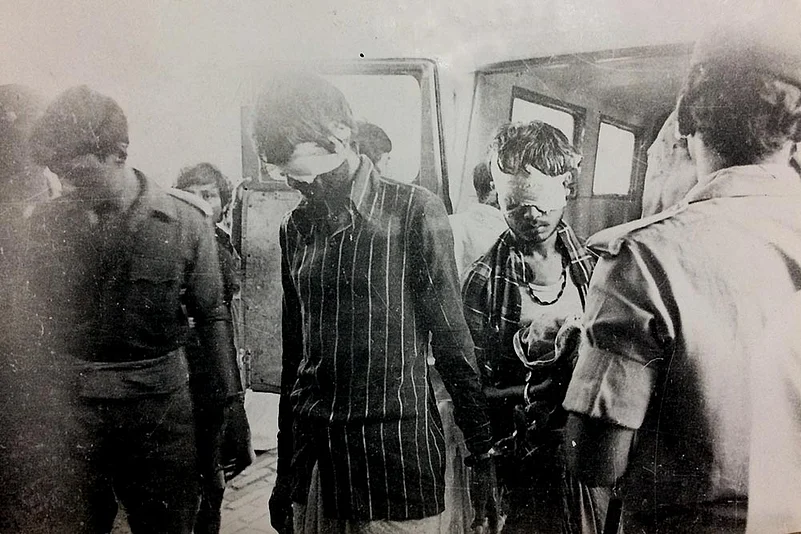

The police blinded 31 undertrials in Bhagalpur, 1979-80

Years ago a joke was doing the rounds: The US president wanted to test the prowess of the CIA, the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). He released a rabbit into a forest and asked them to catch it. The CIA took three months to report that the rabbit did not exist, while the FBI had taken only two weeks to say they had burnt the forest to kill the rabbit. LAPD, though, had claimed success in just two hours and produced a badly beaten bear, which was yelling, “OK, OK, I am the rabbit.”

That was the time when LAPD was infamous for racism, corruption and brutality. In April 1992, the Rodney King riots had raged for six days, resulting in 63 deaths. This was followed by the 1999 Rampart corruption scandal, in which 70 officers of their crash unit were indicted. In 1994, the US Congress passed a law that gave the US Justice Department powers to sue a state or local government in federal court on police misconduct and to ensure that the police adhered to the prescribed behavioural norms.

In 2000, the Justice Department moved a class action suit to place LAPD under federal supervision for improving civil rights, controlling corruption and suppressing gangs. The Los Angeles mayor, who controls LAPD, agreed to the consent decree on June 15, 2001. Those who are interested in reading how police reforms were effected in LAPD should study a May 2009 paper by the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University on the steps taken within the parameters of the court. This paper was considered by the court in releasing LAPD from federal supervision on July 18, 2009. It is an example of how academic institutions can contribute to better governance. In India, though, we keep the media and academics away from administration.

Ours is a deep-rooted problem that originated with two mistakes in our Constitution-making, the way the British created our police as a repressive force modelled on the Irish Constabulary, and the way we developed it as the only agency to investigate all violations of penal laws as well as manage our internal security. No wonder our police force has become a pressure cooker about to burst.

The two mistakes in our Constitution-making, which started under British tutelage from December 9, 1946, are as follows: one, the Constituent Assembly was guided by the Cabinet Mission’s May 16 directive for a “weak” centre to appease the Muslim League; and, two, the assembly copied Schedule 7 of the colonial government’s 1935 Government of India Act as our new Constitution’s Schedule 7, placing police and public order with the states. But the 1935 Act was passed for a different purpose. Explaining the real motive of the British government, Oxford scholar David Steinberg writes, “By giving Indian politicians a great deal of power at the provincial level, while denying them responsibility at the Centre, it was hoped that the Congress party, the only national party, would disintegrate into a series of provincial fiefdoms.”

The Constituent Assembly’s proceedings continued up to December 9, 1950, and Schedule 7 could have been modified at least after our Independence in August 1947. The members could have realised the danger of placing the police under the state satraps after witnessing how nominees in the Interim Government incited killings in Naokhali and Tipperah in October 1946.

As a result, all investigations under every penal law are entrusted to our state police, which have also been tasked with several non-police functions along the lines of what they used to do for the British or the princely states. Over time, the states and the Centre assigned them a mind-boggling array of new and varied responsibilities. Besides investigating crime, they are also asked to demolish illegal shanties, collect fines, issue licences (to eateries, horse-drawn tongas and bullock carts), locate missing persons, impound stray cattle, kill stray dogs, dispose of unclaimed dead bodies, round up beggars, protect mangroves and sand beds, detect illegal building constructions, detect “beef crimes”, regulate dance bars, do moral policing, detect cyber crimes, watch social media, work as ministers’ “telephone orderlies”, collect political intelligence, protect vital installations (offices, factories, bridges or water storage areas), serve summons and warrants on behalf of courts, escort prisoners and important persons, and also undertake counter-insurgency operations. More jobs are added by state governments almost every day.

The only reforms we have done over the years is increasing the size of the police, especially the number of senior officers. What was handled by a junior officer 30 years ago is now entrusted to an additional director-general. No rationalisation of their functions was attempted. In many other countries, central agencies share the burden of investigation and maintain public order with state police. Thus, the strength of the New York Police Department (NYPD) and the London Metropolitan Police has been static over the past 20-30 years. Even Pakistan had formed seven federal police systems such as railway police and the Federal Investigation Agency to deal with specific areas of security and investigation.

Our police are stretched far beyond their capacity to meet the challenges confronting them. The life of an average policeman gets overtly strained when, in addition to his usual police duties, he is also held responsible for a minister’s stolen buffalos (five UP policemen were suspended during the erstwhile Samajwadi Party regime) or asked to trace a BJP minister’s lost pet dog (in Jaipur, a few years ago) even while investigating a case of dacoity and gang-rape. The same policeman is also held responsible if his area is hit by international terrorism.

As a result, investigation work has increased astronomically. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reports that the total number of cognisable crimes in India in 2015 was 73, 26,099, of which only 29,49,400 were major crimes under the IPC, whereas the number under Special & Local Laws (SLL) was 43, 76,699. The Indian police was created for dealing with IPC-defined crime. SLL include social reform laws such as dowry prohibition, child protection or municipal laws. These are highly visible for the media, demanding several man-hours of police work. In many other countries, these are assigned to specially empowered agencies to pursue.

With the largest police force in the world, India is not short of policemen. Russia, the largest country (area wise) in the world, has only 11 lakh policemen, while the US, the second largest, has a little more than 10 lakh employees in law enforcement. India is the seventh largest country, but we have has nearly 30 lakh policemen. Clearly, it is not because of the lack of policemen that we are unable to maintain public order, but due to the use of the police for non-police duties. Unless his burden is lightened, the policeman’s performance will not improve. Even those who advocate police reforms are yet to think along these lines. Even if all seven directives of the Supreme Court are implemented (which the states are not doing), there will be no improvement in performance unless the workload is lightened and responsibility diversified.

(A former IPS officer of the Maharashtra cadre, Vappala Balachandran is the author of Keeping India Safe: The Dilemma of Internal Security.)