The Dravidian movement has been a major political force in the former Madras Presidency and Tamil Nadu for a century, and parties derived from it have ruled the state for much of the past half century. This year marks the centenary of the South Indian Liberal Federation (also called the Justice Party), the first party that claimed to represent a Dravidian community composed of non-Brahmin south Indians. Moreover, it is the 50th anniversary of the initial ascent to power of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), the second ethnic party (after the National Conference) that won a post-colonial state election in India. The other major Dravidian party, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), was formed 45 years ago. The Dravidian movement has shaped many aspects of politics and society in Tamil Nadu, and contributed to political discourse elsewhere in India. It is among Asia’s oldest and most durable ethnic movements.

The Dravidian movement claimed to represent a Dravidian community consisting of south Indians, primarily Tamil speakers, other than Brahmins. Visions of a non-Brahmin community developed earlier, in the late 19th century, in Maharashtra, where those who promoted them joined Indian nationalist parties by the 1930s. In Tamil Nadu, most of them joined the Dravidian parties. While the Justice Party was led by elites from upper non-Brahmin castes, certain later Dravidian parties—the Self Respect Association/Dravidar Kazhagam (DK) and DMK—were led by middle- and lower-middle-caste individuals. The DK’s founding leader, E.V. Ramaswami Naicker (Periyar), was from a wealthy mercantile family and caste (Kavarai Naidu), but the DMK’s leaders, C.N. Annadurai, a Kaikkola Mudaliar (a weaver caste), and M. Karunanidhi, an Isai Vellalar (a musician-dancer caste), were from underprivileged families. The DK and the DMK associated Dravidian identity mainly with the middle castes and the DMK with those who primarily communicated in the Tamil language, to whose history and virtues it devoted much attention. The AIADMK associated itself closely with the lower strata and women through the films of M.G. Ramachandran (MGR) and party rhetoric and periodically asserted the specificity of Tamil Nadu’s political culture, while paying less attention to ethnic identity and being led by individuals beyond the movement’s early ethnic visions: MGR, an ancestral Malayalam-speaker, and J. Jayalalitha, a Brahmin.

Dravidianist discourse also had a populist character, upholding a popular community distinguished from elites based on caste, language use, dialect, occupation and the closeness of one’s links to the government. It helped the Dravidian parties attract various plebeian groups and marginalise Indian nationalist parties far more than in any other big state although attachment to Indian nationalism remained strong in Tamil Nadu. The Congress mobilised masses significantly only in some pockets, and distributed patronage mainly through social elites, bureaucrats and party leaders when it ruled the state until the mid-1960s.

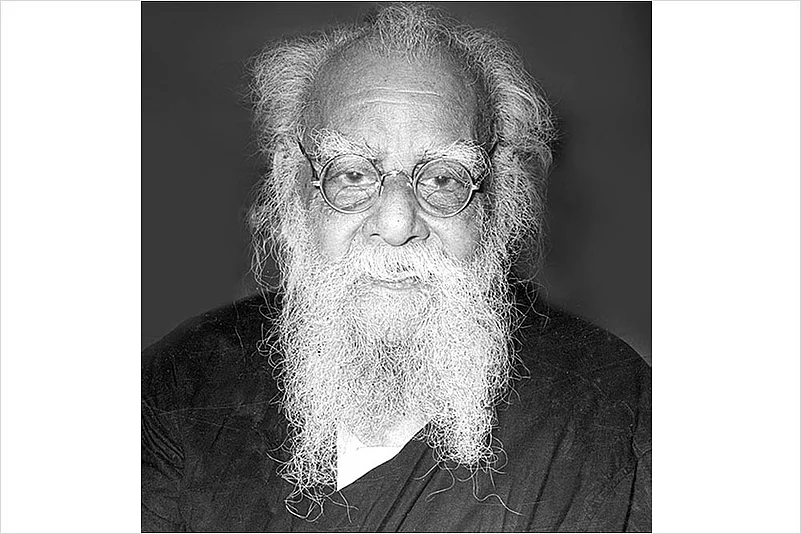

Periyar

The DMK and the AIADMK criticised such narrow patronage distribution and selective social engagement. Many first-generation white-collar workers, small shopkeepers, smaller farmers and artisans were drawn to such criticisms, reinforced by the parties’ attention to caste mobility and Tamil. Many Muslims found in the DK’s and the early DMK’s criticisms of caste inequality and Hindu polytheism greater political acceptance than Indian nationalism offered them. As the DMK became aligned primarily with upwardly mobile groups by the 1970s, poorer people, Dalits and women gravitated toward the AIADMK, as did various ancestral non-Tamil speakers and upper-caste individuals who were marginal to the DMK’s vision.

Dravidianist mobilisation increased voter participation, which has been much higher since the 1960s in Tamil Nadu than in all but a few states: Kerala, Punjab, Haryana and West Bengal. It crystalised party identifications, sharpened party competition and formed a party system dominated by two parties: the DMK and Congress in the 1960s and early 1970s, and the DMK and the AIADMK thereafter.

A young M. Karunanidhi listens to C.N. Annadurai (1909-69), founder of the DMK, the second ethnic party to win a post-colonial election in India

Caste, Language, Community

Tamil Nadu (along with Kerala) witnessed early and extensive middle-caste mobilisation, but was not among the main bases of Dalit mobilisation, which remained much lower there than in Maharashtra and Punjab. Dalits and many OBCs of lowest status had limited representation in the leadership and enjoyed little autonomous voice in the Dravidian parties. Periyar placed Dalits and non-Hindus on the Dravidian community’s margins, and resisted reservation for Dalits soon after Independence when he felt this constrained middle-caste prospects, but his organisations opposed untouchability. Close links with certain big landlords made the DK reluctant to oppose agrarian bondage that limited the lives of most Dalits. The later Dravidian parties were also ambivalent about Dalit projects. Thus, assertions that the Dravidian parties represented low castes are inaccurate. In calling Periyar a forerunner, recent Dalit organisations such as the BSP misunderstand the Dravidian movement.

In its early stages, the Dravidian movement strongly opposed certain ethnic groups, especially Brahmins and speakers of the significantly Sanskrit-based languages of western, northern and parts of eastern India (misleadingly called “north Indians”). The DK and the DMK called for secession early on, from the 1930s to the 1960s, but did not systematically mobilise for this end, as ethnic movements did in Nagaland, Kashmir, and initially Mizoram. Rather, they used this demand to build a distinct political culture and press for greater state autonomy. Realising that strident ethnic appeals and secessionism limited their appeal, party leaders moderated their ethnic orientations and abandoned secession. They did so although the central government did not accommodate some of their central demands—either the DK’s demands to drop constitutional guarantees of religious freedom based on the argument that the free practice of Hinduism necessitates caste discrimination or the DMK’s pressures to devolve more power to state governments. A sign that the movement did not seriously sharpen ethnic antagonisms was that the AIADMK was the most popular party for the better part of the past 45 years although its paramount leaders were not part of early concept- ions of Dravidian identity. The DMK briefly used nati-vist appeals to discredit the AIADMK soon after the latter party’s formation. They failed; and deterred such attempts thereafter.

M.G. Ramachandran inducts a young J. Jayalalitha into politics at a rally in Cuddalore in 1982

Reservation Policies

Pressures from caste associations led the state government to adopt high OBC reservations. Reservations for “Depressed Castes” were introduced in the 1880s; they were extended to the OBCs in 1951, well before the central government did so in 1990. The OBC quota, which was initially 25 per cent, was increased to 31 per cent in 1971, and 50 per cent in 1980. Along with the 19 per cent SC-ST quota, as much as 69 per cent of enrolments in government colleges and government jobs are reserved based on caste, contrary to judicially mandated limits.

A 20-per cent tier was introduced within the OBC quota for the most backward castes and denotified communities (formerly deemed criminal tribes) in 1989, a separate 1 per cent quota for STs in 1989, and a 3 per cent tier within the SC quota in 2009 for Arunthathiyar, the numerous Dalit caste of lowest status.

Hindu Nationalism, Violence

Hindu nationalism has been the weakest in Tamil Nadu (as well as in certain small Northeastern states), crucially due to Dravidianist mobilisation. Hindu nationalist parties polled no more than 0.2 per cent of the vote in state assembly elections until 1991, and no more than 3.2 per cent thereafter, much less than they did not only in their oldest strongholds in north and west India, but also in regions of later growth, such as Karnataka, Assam, West Bengal and Orissa. Hindu nationalism was impeded in Tamil Nadu because the Dravidianists upheld norms at variance with those Hindutvavadis valued—Tamil specificity based in middle-caste cultures, rather than Hindu/Indian homogeneity based on Sanskritic upper-caste norms; and because the DMK built cooperative political links between OBC Hindus, Muslims, and to some extent OBC Christians. Such networks impeded Hindu nationalist growth, dependent on cultivating anti-minority animosities, as well as inter-religious violence, both of which were most limited in the DMK strongholds in northern and central Tamil Nadu.

As they were closely associated with the middle castes, the Dravidian parties did not impede middle-caste violence toward Dalits, which exploded at different points both in the DMK’s early bases in the state’s northern regions and in the strongholds of the Congress and the AIADMK in the southern and western regions. Largely Dalit-based communist mobilisation contained caste violence more in the Kaveri delta in central Tamil Nadu.

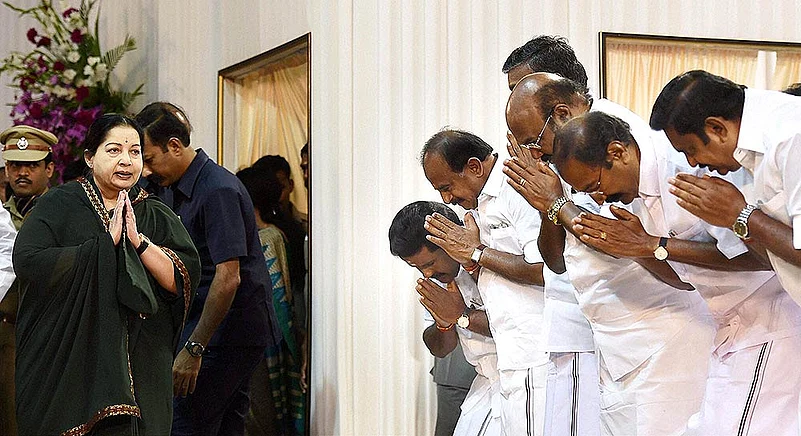

J. Jayalalitha being greeted by party colleagues after taking oath as CM (sixth time) in 2016

Parties and Civil Society since the Late 1980s

In their heyday, the Dravidian parties engaged closely with caste associations, farmers’ associations and trade unions, which nevertheless remained autonomous of them. They ceased to be the main forces mobilising society from the late 1980s although they remained electorally dominant, polling between 60.8 per cent and 73.9 per cent of the vote. Dravidianist social visions framed civil society mobilisation even less thereafter. Many caste associations became dissatisfied with how the state government had represented their concerns, and various other associations also opposed the unequal consequences of the neo-liberal policies the Dravidian parties adopted.

Some of these civil society initiatives led to the emergence of new parties or revival of older ones that mobilised specific megacastes—mainly certain MBCs (Vanniars), denotified communities (Mukkulathor) and Dalit groups (Parayar, Pallar and Arunthathiyar). Other new parties tried to build coalitions across group boundaries. The former parties polled no more than 8.1 per cent of the vote, but influenced popular aspirations and civil society mobilisation far more. The latter parties, of which the Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam alone became important, gained no more than 8.4 per cent of the vote. Thus, the AIADMK’s and the DMK’s electoral dominance faces no clear threat even after Jayalalitha’s passing and Karunanidhi’s gradual retreat from public life although many civil society initiatives have pressed beyond the social visions of these parties.

Narendra Subramanian, is a professor of Political Science at McGill University, Montreal, Canada